The Mekong River in northeastern Cambodia has long sustained vibrant and bustling communities of fisherfolk. But today, the once-thriving industry is facing a double blow that threatens the very fabric of these close-knit communities.

Illegal fishing practices and the construction of dams upstream have dramatically reduced the number of fish in the river, leaving the fisherfolk struggling to make ends meet.

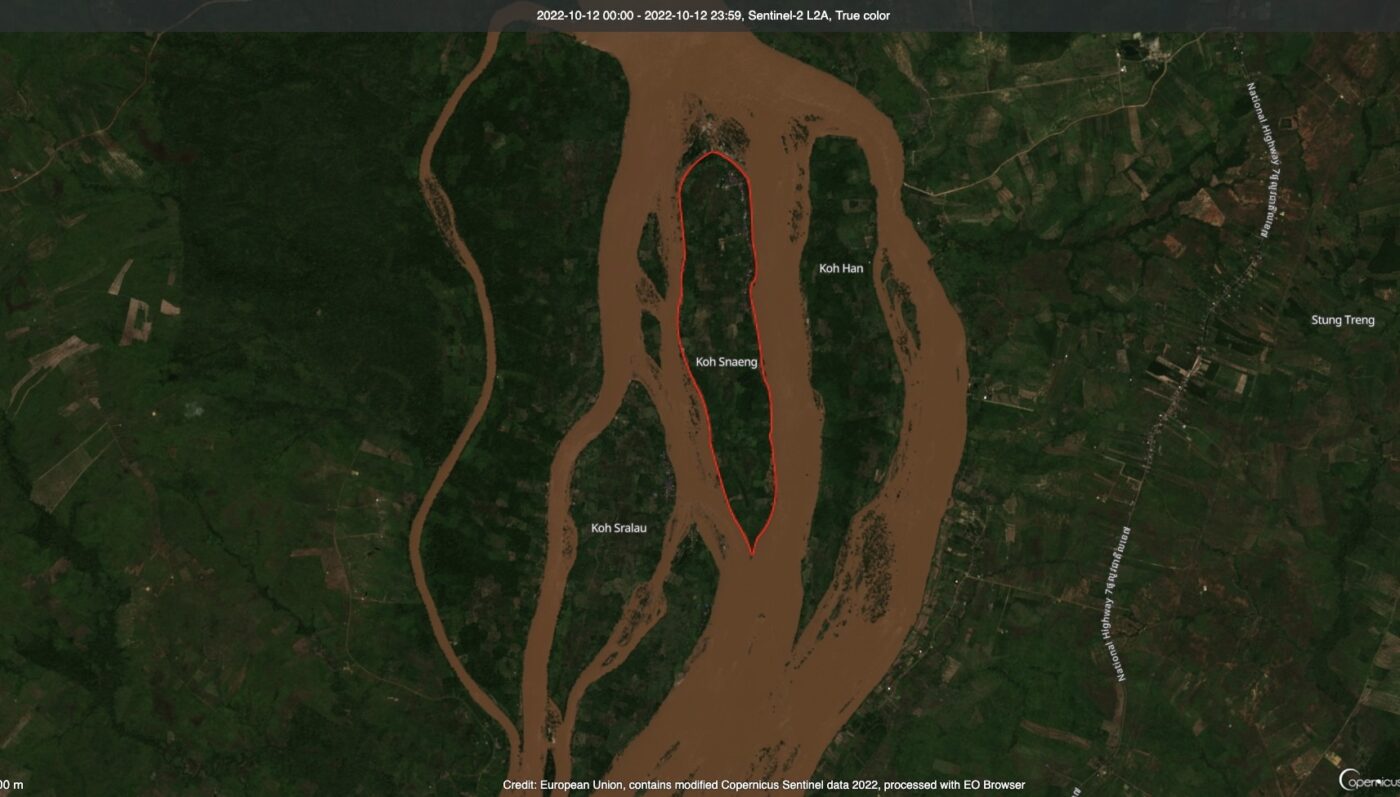

“I just cannot catch enough anymore. Fishing has become very difficult and I don’t know what to do,” said Khai Pae, a 35-year-old fisherwoman in Koh Sneng community in Stung Treng province. The village is located about 60 kilometers from the Don Sahong Dam in Laos that started operating in 2020.

The impact of this crisis is felt throughout the region, as the fisherfolk scramble to find new ways to earn a living. Fish farming, which has been touted as a viable alternative, is proving to be difficult for many due to a lack of support and technical knowledge.

A double crisis

Sok Den witnessed how the situation went from bad to worse. The 40-year-old resident of Koh Sneng used to earn up to $1,900 per fishing season. But by 2018 his income had dropped to less than $1,000. When he could no longer afford fuel for his boat in 2020, he was forced to quit fishing.

“The main reason for quitting was that I couldn’t catch enough fish anymore,” Den said. “All types of fish stocks decreased.”

He tried fish farming after receiving training from the Culture and Environment Preservation Association (CEPA), a Cambodian non-governmental organization, but he was unable to make it work.

“The association only taught us but there was no support like money or materials, and we had to buy the fish species ourselves,” he said. “We had a hard time with water, changing it to keep it clean and not stinky so the fish would still eat.”

Fighting illegal fishing

Kong Kin, a 62-year-old fisherman in Kratie province’s Sambour district, is disabled after losing one of leg in an accident. He has been fishing for nearly 10 years and was once able to earn $25 per day. But he now struggles to make just $5 due to the depletion of fish from illegal fishing methods like electric shock fishing.

“People can’t make enough from legal fishing so they resort to illegal methods to be able to sell fish to the shops,” he said.

Electric fishing takes two forms: “hot” and “cold.” The “hot” method uses low-powered batteries and iron rods joined by jumper cables to stun fish in shallow waters. The “cold” method, however, is far more destructive and involves high-powered batteries run through an inverter, sending an electric field into the water via metal cables, killing all aquatic life within 40 meters.

Although banned by the Cambodian government in 2007 due to the harm it poses to river ecosystems, this fishing method continues to be employed by those who disregard the law.

On the Mekong River island of Koh Sneng in Stung Treng province, Sap Udom, head of the Koh Sneng Fishery community, has worked with the community to protect the local fishing industry from illegal fishing. The 34-year-old and his fellow community members, with financial support from CEPA, patrol the waters during the fishing off-season from May to October, with day and night shifts.

However, during the open season, the budget for patrols is limited and divided among the communities, with only three patrols taking place each month.

“We have to protect the fish, so we patrol as much as we can, once or twice a month,” Udom said.

As volunteers in the fishing communities, Udom and other members face challenges, including threats from perpetrators. “We have a motorboat, but we can’t use it to chase the perpetrators. We only use it to patrol our conservation area,” he said. “If we don’t take action, fish will continue to decline, and eventually run out.”

A viable alternative?

In Kratie province’s Damre village, the non-governmental organization Northeastern Rural Development (NRD) and the district Fisheries Administration are supporting residents to take up fish farming as a means of livelihood. Doung Chantrea, a 30-year-old local, was among the first to receive support from the organizations.

Chantrea and her family dug their own ponds and were provided catfish to raise. She began her fish farming endeavors in 2018, but by the end of 2022, she and her mother could no longer afford to purchase the fish species. Chantrea recounts a lack of knowledge resulting in the death of her fish and substantial losses.

“I lost a lot,” she said. “I released the fish into the ponds immediately without leaving them in the cold first, causing them to die.”

In Stung Treng’s Koh Sneng, many residents also used to be fish farmers, but their numbers gradually declined, with only ten families out of 100 still practicing it, according to Sap Udom, head of the Koh Sneng Fishery community.

“The villagers cannot successfully raise the fish due to a lack of proper methods,” he said. “They just followed the techniques they knew and did not succeed.”

Na Osa, deputy head of Koh Sneng commune, said that the community received support from CEPA with techniques for breeding fish as an alternative to traditional fishing between 2017 and 2019. However, Osa stated that it is difficult to raise fish in Koh Sneng commune.

“When the water recedes, it completely disappears because the island is in the middle of the river,” she said. “Thus, when the river recedes, the water on the island also recedes, so it is difficult to dig a pond.”

Luy Rasmey, executive director of CEPA, did not respond to requests for comment and Sam Sovann, executive director of NRD, declined to speak with CamboJA.

Responding to crisis

Government agencies have begun responding to the crisis of declining fish stocks in the Mekong River. The Department of Aquaculture Development of the Cambodian Fisheries Administration is working with local organizations to promote aquafarming and provide technical support to fish farmers.

“Population growth has led to an increased demand for protein from fish, but modern fishing practices, overfishing, and illegal fishing have left fish stocks unable to meet market needs,” said Thay Somony, the department’s director. “The fishery output is declining, and it cannot fully support population growth.”

The department is focused on 10 target provinces for aquaculture, including six provinces surrounding Tonle Sap Lake, and areas in the Upper and Lower Mekong Rivers. Somony stressed that while aquaculture is crucial, it is also complex, and fish farmers must understand the market, create a business plan and manage their cash flow to succeed.

Regarding the implementation of fish farming in the Upper Mekong region in provinces like Stung Treng and Kratie, Somony noted that the department may consider it, but there are water issues to consider. “During the rainy season, there is plenty of water, but in the dry season, there is a lack of water, which creates a risk,” he said.

The impact of dams

According to Brian Eyler, the director of the Stimson Center Southeast Asia Program, the decline of the fisheries in Cambodia’s Mekong River is due to several factors, the main one being dams that block fish migration to crucial spawning grounds.

The Lower Sesan 2 Dam in Stung Treng province, for example, is expected to reduce the entire Mekong fish population by 9.3 percent due to its poorly designed fish passage, according to some scientists.

The Mekong River is also being deprived of sediment due to the hundreds of dams upstream in countries like Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, and China, with China’s dams blocking 60% of the river’s sediment.

Additionally, the arid wet seasons in 2019, 2020, and 2021 prevented the Tonle Sap Lake, the largest freshwater lake in Southeast Asia, from expanding to its usual size, reducing the number of fish in the lake.

“Raising aquaculture can be a transitional livelihood for fishers, but it requires many inputs such as antibiotics and other substances, which are not necessarily healthy for people,” Eyler said.

He believes that conserving the Mekong’s wild fishery is possible but would require placing greater value on the fishery and food security of Cambodia than currently exists.

“It would take swift and smart action from the Cambodian government through good management practices both domestically and with upstream neighbors,” Eyler said.

“Reporting for this story was supported by Internews’ Earth Journalism Network”.