Yeang Sothearin says he has becomes a “hostage” to politics: His court case won’t end as long as his former employer, Radio Free Asia, keeps up its critical coverage of the government, he believes.

He is like “a rooster locked in chains” while the case hangs over him, unable to work or relax. Yet still he wants RFA to continue on its mission.

Sothearin, one of two RFA journalists arrested in 2017 amid a media crackdown, is caught in the middle of a standoff between the government — which bristles at what it calls foreign interference — and the U.S. and Europe, which have pushed back against the dissolution of Cambodia’s political opposition and several media entities, alleging violations of human and political rights.

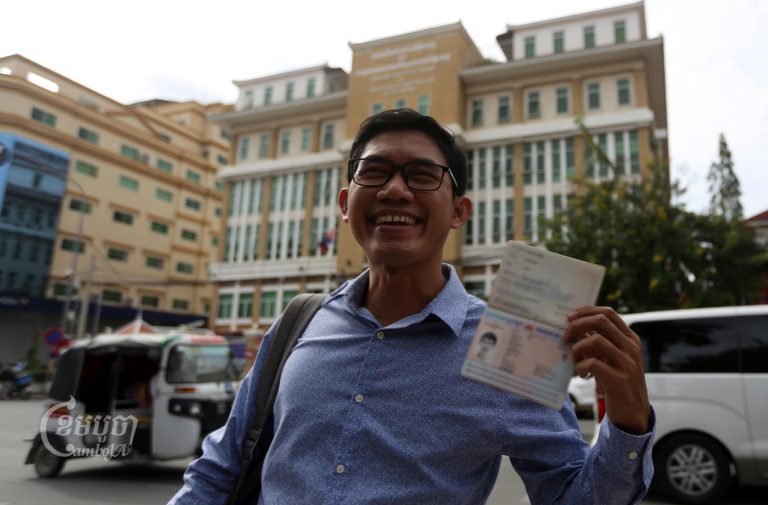

Earlier this month, the Phnom Penh Municipal Court sent Sothearin and Uon Chhin’s cases back to investigation instead of issuing a verdict. The further delay, 23 months after the pair’s arrest for allegedly supplying a foreign state with information prejudicial to national defense, was a blow.

“The trial never ends,” Chhin said. “I can’t concentrate on any other thing.”

Sothearin, who was formerly RFA’s Phnom Penh bureau manager and news editor, said they had become mere bargaining chips for politicians.

“They’ve taken us hostage,” he said.

Sothearin and Chhin were detained for about nine months after their arrest, which followed RFA shuttering its Phnom Penh office amid pressure from the government.

“I’ve seen RFA is still broadcasting online and continues to criticize about bad enforcement by the Cambodian government,” Sothearin said. “So it’s a kind of threat: If RFA continues their reports about Cambodia, our case will keep on going.”

At the same time, however, the courts were reluctant to convict them, he said, amid pressure from the international community.

The situation has left Sothearin in a personal quagmire. But he doesn’t want to see RFA give up its work.

“For me I think and support that RFA should continue their reporting in Cambodia effectively with critical reports for the benefit of the the public,” he said.

Kim Sok, a political analyst who was jailed in 2017 and now lives under asylum in Finland, said the case was political.

“The ruling party [wants] to shut the mouths of people who speak — and the media who report — critically about them,” Sok said.

Still, the government didn’t want to push too far, and by delaying the verdict against Sothearin and Chhin, it was sending a message that Cambodian still allowed some space for media, he said.

Justice Ministry spokesman Chin Malin denied that the courts were under the influence of politics.

“Judges make independent decisions to continue the investigation or drop the charge, and this case is still in the investigation process,” he said.

Sothearin and Chhin’s trial raised questions about whether they continued to work for RFA after it closed its Phnom Penh office, and if they took RFA’s digital records by hand to the U.S. Embassy. It was not explained how those actions might amount to the treason charge against them.

For Sothearin, who maintains his innocence, the situation has felt outside his control.

“I look at myself as really the same as a rooster locked in chains, that cannot go anywhere to find food to feed on and can’t really go anywhere that I want to go, as my leg are in locks,” he said.