As Cambodia’s first expressway takes shape, the costs of development have driven straight through a Phnom Penh neighborhood.

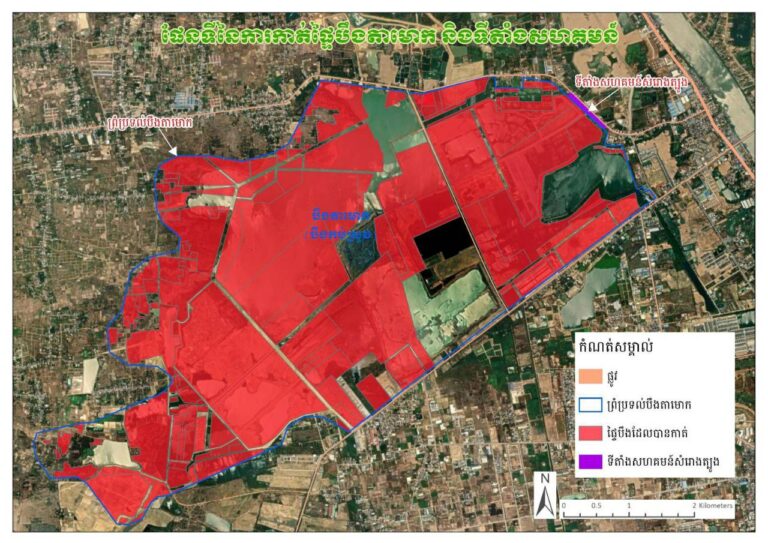

Last week, as many as about 30 families were forcibly evicted with little advance notice to make way for the Phnom Penh-Sihanoukville freeway. Not long after being told to leave, the residents watched a force of some 200 workers and officials demolish their houses along Win-Win Boulevard in Pur Senchey district’s Samroang Kroam commune.

The houses belonged to residents who refused compensation offered by the government, which contests the number of evicted families and says only 10 were included, for the expropriation of their property. Now, some of these families, a few of which are sheltering in tents near the wreckage of their homes, are reporting fears they may never be fully compensated fully for their demolished houses after already being pushed out.

One family now camping near the remains of their house, which was destroyed October 27, denied an interview. Others agreed to speak with CamboJA but asked not to be named, due to fears both for their personal safety but also that authorities will withhold compensation for lost property in retribution.

A 64-year-old man who declined to be named said his house had previously been a total size of 260 square meters. Now, about half of that space has been demolished, leaving him with only 136 square meters to call home.

“I have a land title and I never thought I would meet this day,” the man said.

Several days before demolition, he continued, authorities came to force residents to accept compensation offers. The officials said that if the families ignored them, they would take administrative measures.

“They have only threatened us to accept compensation,” he said. “We have not yet received any compensation.”

He said the villagers weren’t opposed to the development project but needed better compensation than what the government had offered. Though the current market price was about $1,200 per square meter, the main said, officials had offered a rate of just $350.

A daughter of the 64-year-old man told CamboJA by telephone she is currently living with her friend. Her mother and sisters are temporarily staying at a relative’s house in Phnom Penh.

“The compensation is not suitable, only $90,000. I lost my home and my business,” she said. “Here, houses and land are more expensive because it’s not far away from the capital, so they didn’t provide a market price.”

She said that a force of about 200 people had come about 3 a.m. on October 27 to block the road before demolishing the houses. She said her two stories have been destroyed and half.

“After I woke up, I prepared for work as usual, and they had surrounded my home and my village. I saw they were demolishing my neighbor’s houses,” the woman said.

“I was so shocked to see those police surrounding our village, making it look like we are criminals. I have no words to describe my feeling, especially to see tractors damage my house. I can only cry with pain and miss our home.”

She said that her house had two stories and, besides sheltering her family, also included an electrical supply store and two rental shops that provided food and car wash services. Those rental spaces had generated about $600 per month.

“My family also doesn’t want me to talk much because they are concerned about our safety,” the woman said. “The authorities can freeze our compensation because we normal citizens cannot protest against them.”

She called on relevant authorities to reconsider a suitable compensation, rather than forcing a lesser deal on the residents.

Pur Senchey district governor Hem Darith and his deputy Pang Lida both declined comment by referring inquiries to the Phnom Penh municipality.

Met Measpheakdey, spokesman of the Phnom Penh city hall, said the government is focused on finding solutions for the families who have been impacted by the project.

He said that in Phnom Penh there are about 500 affected families, but that all but about 10 have already agreed to accept compensation.

“If you compare a percentage, they do not exceed one percent,” Measpheakdey said, adding that inter-ministerial committees have negotiated with the remaining families many times already.

“The time isn’t good that we need to wait anymore, because the majority of the construction is being built and some areas have been finished. For the rest, where there is no choice, we have been forced to take administrative measures,” Measpheakdey said.

He declined to explain exactly how compensation was set to be offered to families affected by the project, stating the Ministry of Economy and Finance (MEF) is resolving that issue.

Instead, he stressed that the expressway is the first ever in Cambodia and will boost the national economy.

Construction of the expressway, which is being built under the broad umbrella of the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative and will link Phnom Penh to Preah Sihanouk province, began in March. The road will stretch 190 kilometers with a width of 24.5 meters. It will have a green median and barriers on both sides to prevent people and animals from passing through.

The project will cost about $2 billion, provided by the China Road and Bridge Corporation through the Cambodian PPSHV Expressway company.

The expressway developers were not available for comment, but the Chinese state media Xinhua reported in April the road is being constructed on a build-operate-transfer financing model. After completion, the trip between Phnom Penh and Sihanoukville will take an estimated two hours, compared with roughly five hours at present.

Vann Sophat, the business and human rights project coordinator at the Cambodian Center for Human Rights (CCHR), decried the use of forced evictions and demolitions without proper compensation.

“We saw the demolition of their houses as unfair compensation in which some houses were built that cost up to $100,000,” he said.

“We have seen activity that is inhumane, and it is regrettable.”

Sophat pointed out that forced evictions are against Cambodia’s law on expropriation, which states that fair and just compensation is required for any personal property confiscated for physical infrastructure construction or rehabilitation for the public and national interest.

“It is a violation of their fundamental rights to land and housing,” Sophat said of the eviction process for the freeway.

He said CCHR has observed hundreds of families dissatisfied with the impacts of the expressway on their properties.

“People are now afraid to express their opinions” Sophat said, adding that state-sanctioned violence and legal pressure has silenced dissent.

He pointed to conflict and dozens of arrests in relation to land disputes connected to the $1.5 billion mega-airport project being built by the development fIrm OCIC.

Var Sim Soriya, spokesman for the Public Works and Transportation Ministry, said the expressway is about 67 percent finished and is scheduled to be completed September 2022.

“We don’t have a report of resolutions for the impacted families,” Sim Soriya said. He also explained the Public Works Ministry does not have such figures because the inter-ministerial effort to build the expressway is led by the MEF.

He had no comment on the evictions of families in Phnom Penh.

Vei Samnang, the provincial governor of Kampong Speu, looked at the expressway in terms of costs and benefits.

On the whole, he believes the project, which passes through his province, will be a fruitful one.

“The impacts cannot be avoided, but they are smaller than the benefits, so we have to accept this impact and try our best,” Samnang said.

He said the project has run through the land of farmers’ rice paddies and that of six households, but that so far the government has provided market prices with them with market prices for compensation. However, land prices are generally cheaper in Kampong Speu than in Phnom Penh, and Samnang did not reveal the actual rates paid for land.

“Everything cannot make all people happy, and with compensation it is the same,” he said. “Most of them received it, but there is just a small amount of belief in political propaganda and greed. They want more than what compensation provides.”

“For example, their land is sold off for $1 for one square meter, but they want up to $10 which has followed the inciters,” Samnang added. (Additional reporting by Sam Sopich)