Cambodia has lost some 2.5 million hectares of tree cover over the past two decades, a new report by an environmental monitoring group shows, with one of the lead authors saying the government is allowing illegal logging to happen “with impunity.”

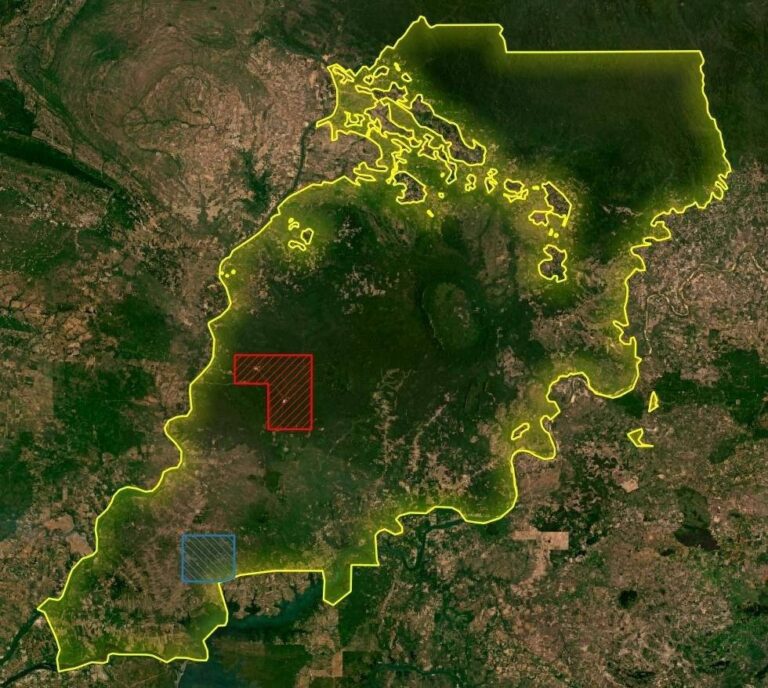

In 2020 alone, Cambodia’s wildlife sanctuaries lost 48,000 hectares of tree cover, the report by Citizens Engaged in Environmental Justice for All (CEEJA) showed, using

satellite monitoring in the protected areas of Prey Lang, Prey Preah Rokar and Sorng Rokha.

The rate of deforestation in Cambodia is one of the highest in the world, the report said, and could have a disastrous impact on climate change and food security if measures aren’t taken to protect the forests.

“Sadly, the record of the Ministry of Environment has deteriorated very fast over the past 2-3 years,” Professor Ida Theilade from the University of Copenhagen told CamboJA in an email.

“The ban and harassment of local forest patrols has led to an increase in illegal logging in Prey Lang and Preah Rokar Wildlife Sanctuaries,” he said. The report shows 2,000 hectares of forest disappeared between 2018 and 2020 alone.

Professor Theilade added that there have long been allegations of an alliance between authorities and owners of economic land concessions on the borders of protected areas.

“Lately, reports abound that MoE rangers in many cases have abandoned check posts altogether and trucks are bringing logs out of protected areas unchecked having paid off the authorities in advance,” he said.

Environment Ministry spokesman Neth Peaktra, however, said there was “nothing new” in the CEEJA report.

“The current state of the protection and conservation of natural resources has improved, the level of degradation has declined,” Mr. Peaktra said.

He added that Cambodia has been protecting and conserving existing natural forests as well as selling carbon credits to volunteer markets since 2016.

Heng Kimhong, a research and advocacy program manager at the Cambodian Youth Network, said the Environment Ministry should study what civil society has found, and strive to protect forests, rather than denying the facts.

“It is new information for the Environment Ministry to recognize the loss of natural resources and tree cover in protected areas,” he said, adding that restrictions on civil society groups who monitor environmental degradation should be removed and legal action taken against those responsible for it.

Sut Savun, a representative of the indigenous Kouy minority in Preah Vihear province’s Brameru commune, expressed his disappointment that Prey Preah Rokar continues to suffer from logging and land clearance for farming, despite being designated a protected area.

“It has impacted the livelihood of indigenous people who have always relied on forest products in their traditional cultures,” he said.

He said illegal loggers continue to take timber out of the Prey Preah Rokar protected area without being arrested by rangers, and lamented the fact that community patrols have been banned.

“In the past, the community patrolled the forest and seized timber from loggers and they were afraid,” he said. Should deforestation continue at such rates, Professor Theilade told CamboJA, temperatures will increase, the onset of rains will be delayed, and Cambodia will experience more frequent fires, droughts and extreme heat waves. A dried out Tonle Sap river, he said, would have a huge impact on food security in the country.