As more former CNRP officials split to form a new party for the upcoming election, political observers are cautioning that quality beats quantity when it comes to building a competitive opposition.

The Kampuchea Niyum Party is just the newest of six political parties created as an offshoot of the country’s former chief opposition group. Yem Ponhearith, who founded the new party and is a former CNRP senior official now living abroad, did not respond to questions from CamboJA. However, he told local radio in an interview that the party had last week submitted for approvals from the Ministry of Interior.

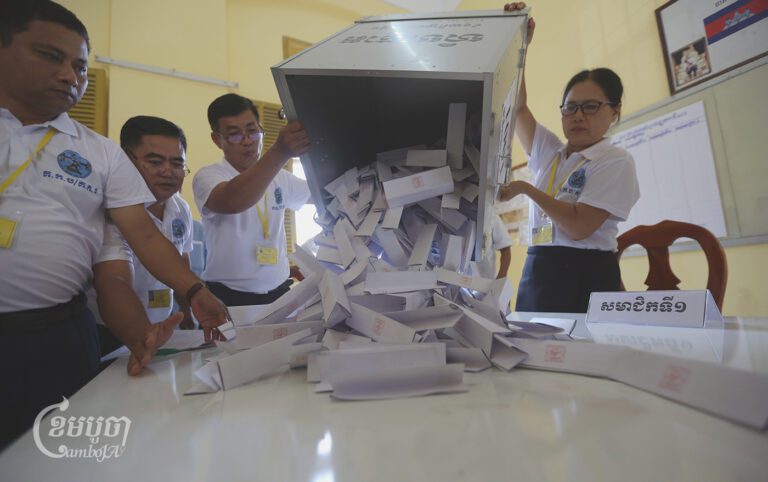

The parties formed by former CNRP leaders now include Khmer Will, Cambodia Reform, Khmer Conservative, Kampuchea Niyum, Cambodia National Love and Cambodia National Heart. These parties will presumably be on the ballot when Cambodian voters go to the commune council elections on June 5, 2022, and the general elections in July 2023.

Sophal Ear, a Cambodian political commentator and associate professor at Occidental College in California, said party shuffling and consolidations have long been in the playbook of the ruling CPP. Sophal said the CPP has not succeeded by playing fair but rather using the organs of state power to get rid of its enemies.

“FUNCINPEC was a real opposition party in the run-up to 1993. When it won, it was not allowed to take over. It had to share power,” he said, referencing the royalist party that proved victorious over the CPP in the election overseen by the UN Transitional Authority in Cambodia. “Eventually, it was co-opted through violence [in 1997] and eventually through corruption.”

Sophal said the ongoing move by former CNRP officials to create new parties to compete with CPP is based on the belief that the court-dissolved party does not have a future going forward. If that’s the case, the opposition might see creating new parties as the only way to create political space in Cambodia.

“The basis has to be that they offer an alternative, but voters should be aware that once you play the CPP’s game, whether you are sincere or not in representing the millions of Cambodians who are not CPP followers, you risk being manipulated,” he said.

FUNCINPEC won the first general election in 1993 organized by UNTAC and joined CPP to form a coalition government from 1998 until the 2013 general election. After years of declining influence, the party failed to win a single seat in the National Assembly.

However, the CPP still faced growing competition in the 2013 general election when the opposition CNRP won 55 seats compared to 63 seats won by CPP. The opposition continued to win more than 5,000 commune councilors in 2017.

The increasing success of the CNRP is believed to have motivated its court-ordered dissolution of the opposition by the government led by the CPP. Many members of what was once the country’s strongest opposition party remain in prison or in exile abroad after being accused of treason or other crimes as part of the dissolution.

Looking at the proliferation of spinoff parties, Kin Phea, director of the Royal Academy of Cambodia’s International Relations Institute, said the tactic of forming new groups is a political choice. However, he said the plethora of new parties may find the chance of actually gaining a seat is too small.

“The more parties they form, the less support they receive,” he said. “Because if we think about the electoral system in Cambodia, the more dissenting it is, the more likely it is for a larger party to win seats.”

Some opposition members are well-aware of this dynamic. Ou Chanrath, founder of the Cambodia Reform Party, expressed concern over the prospect of splitting former CNRP officials.

“We are worried about this. Since the start, we have discussed with each other to re-establish a single opposition party,” he said. “But the talk failed because some conditions were not accepted by individuals.”

Chanrath said the competition needs unity against the CPP, which he said is a big force that will be difficult to compete against.

“I think that the opposition movement may face the same fate as FUNCINPEC if we remain weak and go separately,” Chanrath said. “We will follow the FUNCINPEC model.”

Yeng Vireak, president of the Grassroots Democracy Party (GDP) said he encouraged other political parties, including the newly established ones, to work hard enough to present themselves as a better choice for voters in particular communes throughout the country. He resisted the idea that merging opposition groups was key to competing against the ruling party, suggesting that such a dynamic suggests there could only be two political parties: The ruler and the challenger.

“Though mergers might work somewhere at some points in time, real cases have shown [mergers] hardly worked or did not work at all,” he said. “However, we suggest there must be an enabling environment for all political parties to exercise their political rights to compete in free and fair elections.”

CPP spokesman Sok Eysan said the ability to form a new party showed the ability to exercise political rights without any threats or harm. He rejected the claim that CPP was interfering with other parties.

“The opposition group always accused the CPP of interfering with their internal party which is not true at all,” he said. “They always prevent their members from joining new parties because they are more isolated.”

“If they do not do anything to overthrow the legitimate government, we will consider reinstating their political rights,” Eysan said of former CNRP leaders, many of whom have otherwise been restricted from participating in politics.

Pa Chamroeun, president of the Cambodian Institute for Democracy said that having multiple political parties is an important element in democratic society, but does not really mean there will be a competitive election.

“There will not be a free and fair competition if those political parties do not have enough qualifications and capacities,” he said. “For the time being, I am not so sure that the upcoming national election will be a competitive one.”