Mom Sanang is a primary school teacher in Kampong Speu province who is worried about his students. Under normal circumstances, he sees a number of students drop out around Grade 6 to work at local factories and earn a living for their families.

The COVID-19 pandemic and close to seven months of school closures this year has only increased his anxiety over student retention. A combination of economic hardship at home caused by the loss of jobs and inability to access online teaching tools, is increasing the possibility of school dropouts.

“Generally, even without COVID-19, students from Grade 6 leave school to find jobs at a factory. Teachers are asked to persuade them back to school but it never happens; they need to earn money for their families.”

Sanang said teachers are now printing daily lessons and exercises three times a week and handing them to students in the hope that they will continue their studies.

Like many other countries, Cambodia shutdown public and private schools in mid-March, as the number of novel coronavirus cases jumped from the one case reported in January.

The government has since attempted to increase online pedagogy; publishing grade-specific videos on national broadcaster TVK, YouTube and the Education Ministry’s Facebook page. But the effectiveness of these videos has been under question given the lack of smartphones and affordable data in rural areas of the country.

The uncovering of two recent clusters since early November has further resulted in the critical national examination for Grade 12 students to be pushed back to mid-January, affecting students’ professional and educational prospects.

The World Bank released a report in early December showing that the COVID-19 pandemic and school disruptions could push 72 million additional primary school children into “learning poverty.” The development bank defines “learning poverty” as students who are unable to read and understand a simple text by age 10.

According to the World Bank, at its peak, 1.6 billion students were out of school in April, with 700 million students still affected by school closures. Using Education Ministry data, UNESCO estimates that 500,000 students from nearly 800 schools in Cambodia had been affected by the school closures since March.

Dy Khamboly, the Education Ministry’s spokesperson, said the short duration of school closures makes it hard to evaluate if the current teaching efforts were working or not. He, instead, wanted appreciation for the Education Ministry’s efforts.

“We need to appreciate the ministry’s measures rather than asking how it has impacted the quality of education,” he said.

“We don’t have any indicators to measure how COVID-19 has affected the quality of education for this short period. We just know there has been an effect in general because schools are closed.”

Khamboly said developing partners were recognizing the efforts made by the ministry to pivot to online schooling, which he said was widely accessible to students.

“We have no choice but to use digital [tools] to help students continue their studies safely and it is the solution,” he said.

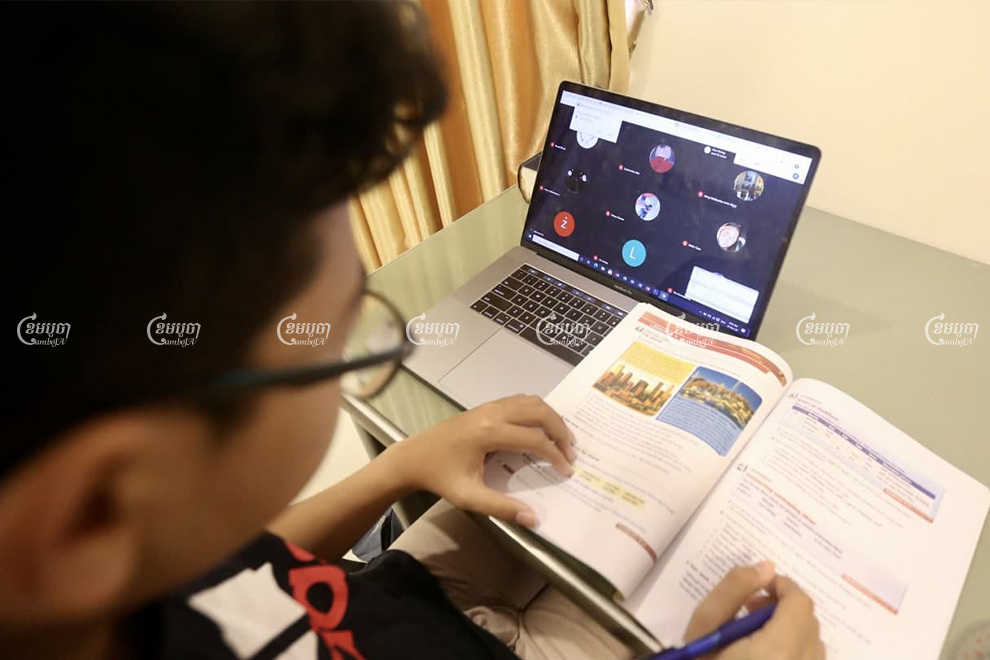

Yang Morokot, who finished Grade 11 at private school in Phnom Penh, said that even though she had access to the online tools and reliable internet, it was hard for her to understand or clarify her lessons.

“Teachers explain [lessons] via Zoom and sent us the lessons and exercises by Telegram,” she said, referring to a video conferencing and messaging application, respectively.

“But, it is hard for me to understand [the lessons] because we cannot ask the teacher [questions] directly and the teacher would sometimes respond a few days later,” she said.

The 17-year-old student said she was worried that if online classes continued into next year, she might not pass the Grade 12 examinations.

Pech Bolen, president of the Federation of Education Services in Cambodia, said there was a risk the school disruptions would affect the scores of students in higher grades, however, there was still time to correct any failings with primary school students.

“Yes, it will definitely affect [students]. I mean their score will fall from ten to seven or six this year,” he said. “However, for [primary] school children there will not be a strong impact as they still have time to catch up.”