Young Cambodians are voicing growing concern that mandatory military service will deepen their financial woes, as the country prepares to expand conscription in 2026.

With more than half of adults already in debt, some fear being pulled from better-paying jobs for two years could push families further into hardship.

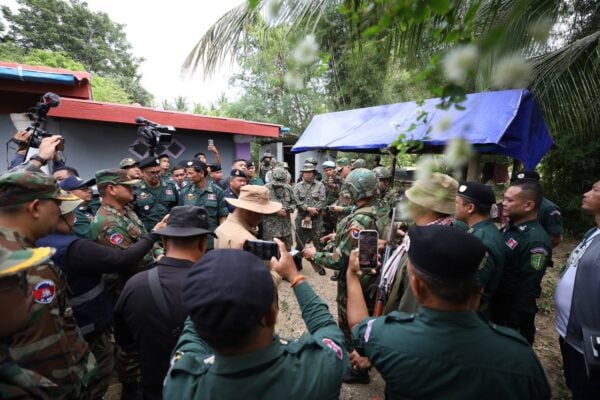

At a Military Police Day event on July 14, Prime Minister Hun Manet – himself a former army commander – announced plans to amend Cambodia’s 2006 conscription law. The change aims to boost military capacity and comes amid rising tensions with Thailand.

Manet proposed increasing the duration of mandatory service from 18 to 24 months for all Cambodian men aged 18 to 30. Enforcement of the law has historically been lax, and most women serving in the military are volunteers.

The prime minister asserted that extending conscription would improve recruitment efficiency and instill “discipline and order among citizens.”

The Senate must still vote to confirm the amendment – a step that typically favors the executive, given the ruling party’s near-total control of the chamber and its four-decade grip on power.

But as it moves forward, young men and defense analysts are calling for a shift from compulsory to voluntary service and a better financial safety net for conscripts.

Eung Sea, 27, a freelance journalist in Phnom Penh, said conscription could deal a blow to young people carrying family burdens.

“Many Cambodian youth have vital responsibilities to support their families, including funding siblings’ education like I do, and helping with urgent needs like paying off debt,” he said. “Being forced to serve for two years could disrupt these contributions and threaten family livelihoods due to the lack of guaranteed income.”

Under Article 10 of the current conscription law, service members receive a one-time severance payment after their service period and “other benefits for daily living,” though details are unclear. The monthly salary for the lowest-ranked soldier is about $345.

Sea warned that a prolonged absence from work could erode skills and hurt productivity after service.

“There’s also uncertainty about job security – many people like me worry they won’t regain their positions, salaries, or benefits unless the government enforces protections,” he said.

Most importantly, he called on the government to establish a fund to support conscripts’ families and prevent loss of income during their service.

Others echo concerns about the economic and social costs of compulsory service, calling for a more flexible approach.

Pich Chantrea, a Cambodian defense analyst based in the U.S., said he supports expanding military service but favors a voluntary model over compulsory enlistment for young men.

He said the government must address key concerns, including economic disruption, budget strain, risks of troop quantity over quality and ongoing corruption.

“Given these challenges, a voluntary model is more practical. It attracts people who actually want to serve, which boosts morale, commitment and performance,” he said.

“It also avoids putting financial pressure on those who aren’t ready or able to serve – especially in a country where many young people support their families.”

Chantrea said he faced those same pressures while training in the U.S., juggling intense academic and physical demands with constant worry about relatives in Cambodia. His grandmother’s food, his aunt’s cancer and HIV, and his sisters’ education were never far from mind.

Although he received a small stipend, it was not enough. He took on part-time work to send money home, and said many Cambodian youth from modest backgrounds could face even greater hardship under mandatory service.

Thailand, whose military manpower is estimated to be more than twice Cambodia’s according to the annual Global Firepower defense review, has signaled it may scrap its lottery-based conscription system.

Several political parties, including the progressive Move Forward Party and the ruling Pheu Thai coalition, have pledged to end mandatory service and shift to voluntary enlistment.

One driver of Thailand’s reform agenda, which preceded rising border tensions after a deadly clash in May that killed a Cambodian soldier, is the impact mandatory service has on household finances and education, regional geopolitical observer Seng Vanly noted.

He stressed that in developing countries like Cambodia, the economic power and productivity of young workers are vital to national progress.

“I do not agree with military conscription, but I support modernization in the military sector,” Vanly said. “Modernization does not require conscription. Instead, promote economic growth, invest in military technology and modern defense systems, and cooperate with other countries.”

“While the economy struggles, the government should focus on boosting productivity and harnessing citizens’ skills to grow Cambodia’s economy.”

Government spokesperson Pen Bona declined to comment on the proposed conscription changes, saying the amendment has not yet been finalized. Ministry of Defense spokesperson Maly Sochata did not immediately respond to a request for comment.