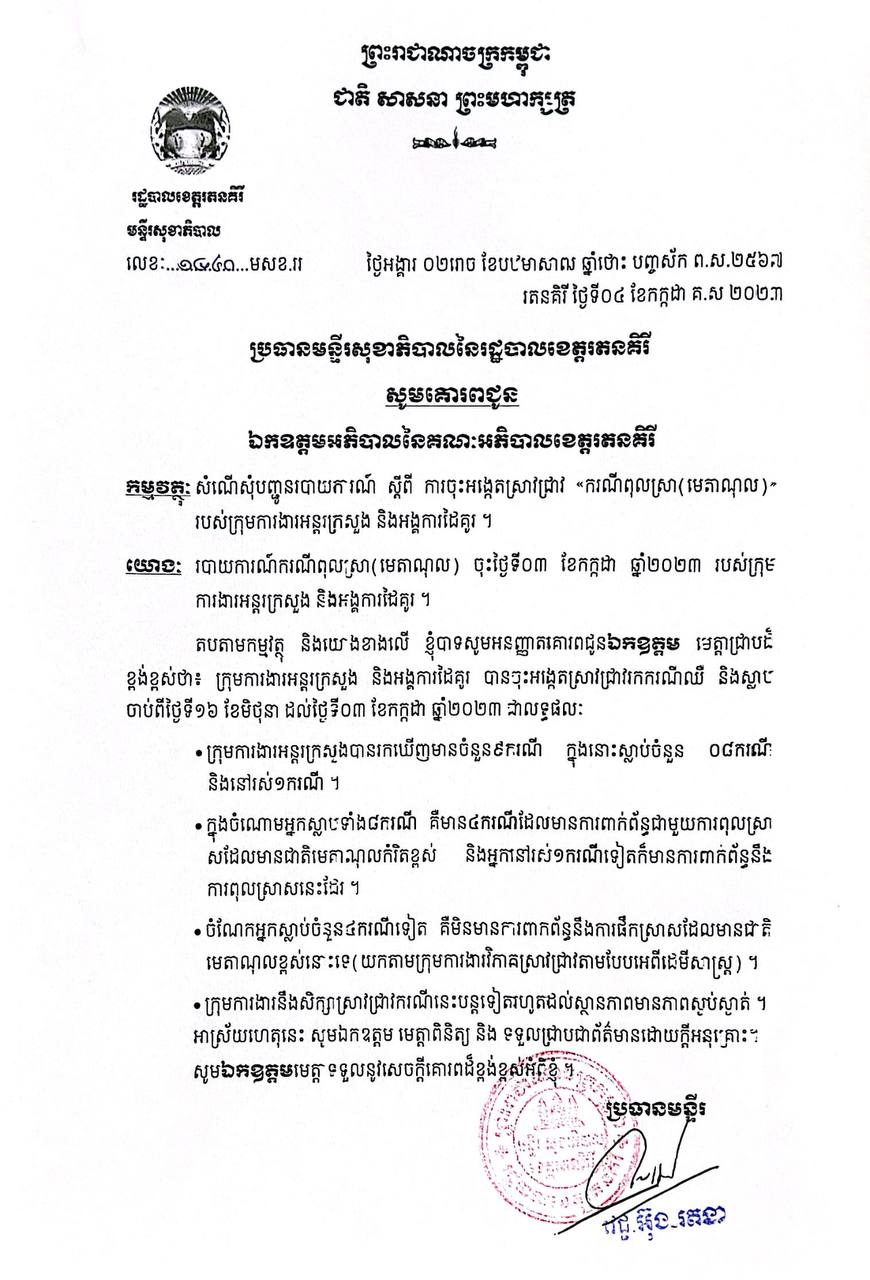

Kon Mom District, Ratanakiri Province – July storm clouds rolled through the sky as

Chhan Yen sobbed while surrounded by family and neighbors standing by with dejected postures and vacant gazes in their village of Sre Angkrong.

Through tears, Yen recounted her husband’s arrest following the death of their 24 year-old son and eight to 12 other men in June, allegedly due to contaminated rice wine. Yen and her husband were among six detained for buying and selling rice wine which the Consumer Protection, Competition and Fraud Repression Directorate-General (CCF) claimed had fatal amounts of methanol.

An official report published on July 4 by the Ratanakiri Health Department, the Health Ministry, the World Health Organization (WHO), and the US Center for Disease Control (CDC) found eight men died—four due to rice wine, while no cause of death was listed for the other four. A ninth person experienced sickness but survived.

Even though only half of the deaths were attributed to rice wine and the investigation is ongoing, six rice wine suppliers and distributors, including Yen’s husband, were arrested and charged with involuntary manslaughter, carrying a one to three year prison sentence.

The majority of the victims were migrants from other provinces who had been working at the neighboring 25,000 hectare Thaco Agri banana plantation, run by Vietnamese conglomerate Thaco Group. The official report claimed eight of the nine victims were plantation workers, and seven of them lived on the plantation, but an investigation into the plantation was swiftly curtailed. The eight deceased were all men between their twenties and sixties, the report states.

Unanswered questions linger for community members, who remain concerned about the plantation’s impact on their health and fear lack of due process and conflicting official statements mean rice wine sellers were scapegoated by authorities.

“My son has already died and now my husband is in jail,” Yen pleaded. “I need justice and I have a heavy responsibility in my family now. Please release my husband, he did nothing wrong.”

Ratanakiri’s governor Nhem Sam Oeun said that even after investigating, authorities were unsure of the cause of all the deaths and how many people died. But he dismissed concerns that conditions at the plantation led to any of the deaths.

“There is a confusion about the number of victims, the experts and our team found out only four people died because of rice wine, while the other victims were not related to rice wine,” Sam Oeun said on July 19. “We are sure that those four workers died because of the rice wine, while other people died because of old age or illness, but not related to chemicals [pesticides, herbicides or fertilizer sprays].”

While the official report indicated the need for further investigation into the unresolved deaths, Eung Ratana, director of Ratanakiri’s provincial hospital, told CamboJA on August 16 that the investigation was closed and that the other four individuals died from undefined illnesses and old age.

Mysterious Plantation Deaths

Hidden behind a vast grid of fields filled with rows of banana trees, Dorm Two compound—where the deceased workers once lived—is composed of 36 blue warehouses filled with makeshift walls to delineate sleeping quarters for whole families. The hall in each building is lined with sinks and makeshift, communal kitchen stations. Many migrant workers live there with their families, and there is even a section of one warehouse used as a schoolroom.

When CamboJA arrived in mid-July, several weeks after the deaths, the living quarters of the deceased workers had already been reassigned to new migrant workers and the families of the victims had already left, according to dorm residents.

Officials’ statements and reports have included multiple discrepancies, including how many people actually died and why they died.

Despite suggesting the poisonings were related to pesticides in his initial public statements, Ratana told CamboJA on July 19 that authorities had stopped looking into the banana plantation’s unsafe practices as a cause of death.

Ratana said nine people were poisoned, but only four died and five recovered. Ratanakiri’s governor initially gave a total of ten dead.

But more than 10 community members and three plantation workers claimed that 12 men had actually died, 10 of whom were plantation workers living in the same Thaco Agri housing unit, Dorm Two.

Ratanakiri’s governor, Sam Oeun, told CamboJA that there have been concerns about the banana plantation’s unsafe practices in the past regarding its use of pesticides and chemicals, but explained that the deaths of the plantation’s workers could have been influenced by many different factors.

Bowls and dishes were piled high at many of the communal kitchen stations in Dorm Two, and fly covered glue traps adorned other stations. Besides methanol, Sam Oeun blamed poor hygiene for the death of the workers. He told CamboJA that poor hygienic conditions and practices may have led to workers to consume pesticides in their food.

“This company breaks the rules and lacks cooperation with the provincial governor” by going against labor laws, Sam Oeun said. “We used to advise them to provide a good household environment. We used to punish them because they didn’t have a health station.”

In the midst of men from Dorm Two dying, Thaco Agri publicized on their blog that they gave 68 primary school-aged children living in dorm two 462 gifts, mainly blue Thaco backpacks matching their blue warehouse homes. This gift giveaway occurred on July 3, just as the deaths were being covered by local media.

A woman who has lived in Dorm Two for more than four years, who declined to provide her name, said that two elderly men passed away in the next quarter. She did not know the exact cause of death, but assumed that they were seriously ill and chronic alcoholics.

“I do not know what they died of, but they were sick prior to their death,” she said. “They all drank alcohol after work and had symptoms of headache, coughing and sore throat after work anyway.”

A supervisor at the banana plantation, who gave his name only as Savath, said that all the men who died from Dorm Two worked with pesticides and were exposed to chemicals that had negative effects on their health. He said the chemicals often get in the workers’ food and drinks, including their wine.

Employees often spray chemicals into the air while at work, and then consume those chemicals when they don’t carefully wash their hands or clothes while cooking and eating at Dorm Two, Savath said. He believes the deaths could have occurred as a result of a combination of wine and pesticides.

A 2021 CamboJA investigation into the health hazards of industrial pesticides found that Thaco Agri did not provide personal protective equipment. When CamboJA reporters returned this July, they again witnessed workers, some who looked to be teenagers, spraying pesticides without proper protection.

The official report from July 4 also noted, in a single sentence, that people did not wear proper protective equipment and the dorm was unhygienic.

None of the dozens of workers CamboJA observed wandering through the rows of banana plants carrying plastic drums filled with pesticides wore substantial personal protection equipment. They only wore makeshift face coverings made of cloth kramas or bandanas. Some wore nothing at all.

The Thaco Group did not respond to emails from CamboJA. But the company’s Ratanakiri general manager Le Thanh Hoang announced in July that Thaco Agri plans to recruit 9,000 more workers for banana packaging and cattle farms.

Rice Wine Poisoning

A few days after the official investigation into the worker deaths commenced at the end of June, officials’ statements began attributing deaths to local rice wine production.

Pesticides on banana plantations have been documented as a cause of health problems and persistent respiratory symptoms amongst workers, but rice wine with methanol has also been responsible for mass poisonings across Cambodia. A funeral in 2021 capped off at least 30 deaths within a month from three different incidents.

A mouthful of pure methanol, or approximately 30 milliliters, can prove fatal according to Doctors Without Borders. Phan Oun, the director general of CCF, was quoted by the Phnom Penh Post saying the rice wine samples in this case contained 10-18.8% methanol, a lethal amount. But the official report states there was one barrel with more than 10% and one that was 8.21%.

Nausea, dizziness and chest pain have been associated with pesticides before, including the chemicals imidacloprid and carbendazim identified as being used on a Thaco Agri plantation in Cambodia, according to the NGO International Tropical Fruits Network. CamboJA was unable to determine what chemicals were used at the Ratanakiri plantation.

Doctors and staff at both the Sre Angkrong and Kon Mom health centers were instructed by superiors to not comment on the diagnosis of the patients or the investigation. However, before they were instructed to do so, Sre Angkrong medical center volunteer Him Thomea told CamboJA in early July that plantation workers came in vomiting with symptoms of pain and seizures.

The official report stated that all nine men suffered from dizziness, blurred vision, suffocation, stomach pains and vomiting; all these symptoms align with signs of methanol poisoning, according to Doctors Without Borders.

Rice wine seller Yen says her 24-year-old son Chhan Phanith died on June 19 after suffering fits of coughing, dizziness and nausea.

He hadn’t eaten a proper meal for three whole days and only drank rice wine after his wife left him, explained his mother. He felt unwell, and in turn asked his grandma to treat him with a traditional coining treatment. His condition quickly worsened and it was too late by the time he made it to a doctor. But Yen and some of her neighbors believe it was not methanol that killed her son.

“I am sure that if he died because of the rice wine, everyone else and I would have died too, because we all drink the same wine,” said Leuk Lort, a neighbor who drank from a jug the consumer protection agency reported had lethal amounts of methanol. He said he experienced no symptoms.

Evaluating symptoms alongside patient history can “typically give a very good clue on whether this is pesticides or toxic alcohol,” wrote Knut Erik Hovda, a clinical toxicologist from the Norwegian Centre of Medicine, in an email to CamboJA. He said methanol poisoning typically has “delayed symptoms.”

While not toxic in itself, methanol takes 12-24 hours to produce highly toxic formic acid within the body, and this delay can be extended because methanol is normally consumed alongside the most common antidote, ethanol, in alcohol. Without specific care, patients can die in a couple of days, Doctors With Borders notes.

The consumer protection agency’s statement to CamboJA on July 19 explained that five of the 143 rice wine samples tested from around the area contained lethal amounts of methanol. No rice wine was found at the dorm of the men who died. According to the official report, samples were taken from the distributors just outside the plantation’s gate.

“Consequently, three suspects were found and four samples of rice wine were collected,” the consumer protection agency stated over email to CamboJA. “[Out of] the four samples collected, two of those samples are positive of methanol with an over permitted level.”

The three samples account for the wine sold by the three husband and wife pairs initially detained, including Yen and her husband.

“All the positive samples were seized and destroyed to prevent them from reaching other consumers,” the consumer protection agency noted over email. “To prevent this tragedy, CCF directorate-general also disseminates [information] to the winemaker on the proper use of wine ingredients and the making process as well as the risk of outbreak.”

These tests were conducted at the consumer protection agency’s Ratanakiri laboratory in conjunction with local authorities and WHO’s Cambodia office. Results were later verified in labs at CCF headquarters in Phnom Penh.

Communications officer Lisa Smyth issued a comment on behalf of WHO Cambodia that the organization “supported the Ministry of Health and the Ratanakiri Provincial Health Department with a health outbreak investigation and response in the past two weeks.”

However, Smyth stated any official comment on the findings of this investigation should come from the Ministry of Health.The CCF said the Food Disease Outbreak and Response Team (FORT) under the Ministry of Health was in charge of the investigation..

Health Ministry spokesperson Ly Sovann did not respond to calls or messages requesting comment from CamboJA.

The US CDC was listed in the official report as affiliated with the investigation, but the US Embassy referred CamboJA to the Cambodian CDC under the Health Ministry.

Community Confused and Concerned

Since his elderly parents were arrested and charged with manslaughter for producing and selling tainted wine, Chan Ratana has been running their small general store along with his barbershop. He says he remains confused as to why his parents are being rushed into legal proceedings when he claims the consumer protection agency tested his parents’ rice wine twice and determined it was clean.

The consumer protection agency did not respond when CamboJA asked about Ratana’s allegations.

“I do not think this is a trivial matter. Before accusing anyone, we need to find more specific evidence,” Ratana exclaimed. “The police have just told me to wait while I have to take care of the family alone.”

As of August, Ratana said his parents have not been released and are awaiting trial, but he hopes they can get out on bail.

More than a dozen villagers who spoke to CamboJA believe the plantation and its pesticides played a role in the deaths.

A 45-year-old villager who worked at the plantation for several years said that she believes the poor hygiene of the plantation’s working and living conditions, along with the lack of protective gear, contributed to or caused the deaths.

“In the farm they use many chemicals for the whole banana plant, while the workers at the household regularly lose consciousness because they still have chemicals there,” she claimed, declining to provide her name for fear of repercussions. “They use big vehicles that spray the chemical on the farm even if the worker is working near the line of bananas. They even use drones to spray it over the farm.”

She regularly experienced dizziness, labored breathing and vomiting when she worked at the plantation until 2021, she said. After quitting, her health improved.

Like Yen, family members of other arrested wine sellers were confused by the investigation. Yen said she bought the rice wine from the seller near the gate of the banana plantation just to further redistribute it amongst her neighbors, none of whom died.

Cheu and her husband ran this store near the gate and she explains the police arrested her husband by charging him with selling poisonous products and manslaughter. After questioning her for a night, they released her, but not her husband. He was one of the six arrested, currently facing charges in court.

“[Authorities] don’t put pressure on the company because the company is rich,” she claimed. “The authorities didn’t investigate the company, they only blamed the rice wine seller. We are just an egg that can’t fight with a stone. Who can find justice for me?”