Map, a 35-year-old whose family has lived about 20 kilometers from Angkor Wat for generations, doesn’t want her two children to have to walk a dirt path to use the outdoor toilet behind their home. But authorities told her family they will remove the half-meter wide cement path that Map’s family recently built, saying they did not have permission to build it.

“Every day is like living in a prison. We are under so much pressure that we can’t do anything,” said Map, who asked to be identified by her nickname for fear of further issues with authorities.

The resident of Ampil commune in Prasat Bakong district sees no connection between her family’s desire for the walking path and the preservation of the ancient Angkor Wat temple complex, though that’s the reason that authorities gave.

“I live far away from Angkor temple. How is it impacted?” she said in February.

Residents like Map who made their lives in Siem Reap’s Angkor temple complex have tried to maintain their homes, in spite of a mass eviction campaign that’s led by the government’s Apsara Authority and implicitly driven by the site’s Unesco World Heritage status.

Authorities since 2022 have enforced conservation area zoning around the Angkor Archaeological Park that was apparently set when the park received its World Heritage status 30 years before, leading to a mass eviction campaign that has been criticized for improperly informing residents and violating their rights.

As the campaign went on, residents complained of dismal conditions at the Run Ta Ek relocation villages, with some leaving their land, while officials sued villagers for alleged damage and obstruction by trying to stay in their homes.

Some residents have not received eviction notices yet and so decided to keep their generations-old homes inside the conservation zone, but staying means they must endure constant watch by the special heritage conservation patrollers, the Apsara Authority, who they say have restricted their ability to live in peace.

CamboJA News spoke with over 20 residents across seven communes – either designated as protected areas of the Angkor temples or their community relocation sites – who now say they struggle to live under Apsara Authority control.

Permission Required

Loun Lat, a 44-year-old villager from Rolous commune’s Chambak village, said he didn’t understand why the Apsara Authority would reject his attempts to improve his home’s hygiene.

Lat said he had already received funding in 2015 to build a toilet at his home, as an alternative to burying waste as they had in the past. He decided to build a toilet even though Apsara officials rejected his requests and later warned him for it.

For Lat, the rejection was confounding, against the progress of society.

“We need to have sanitation because our current society has developed. We can’t just defecate anywhere like in the past,” he said.

Rolous commune chief Oum Vong says that 10% of the 9,000 families in his commune do not have proper toilets or latrines. For some, this is due to a lack of funds but for others, Apsara did not approve their requests.

“They are not allowed to build new constructions [without Apsara’s approval],” he said.

Apsara Authority spokesperson Long Kosal claimed that officials never denied a request to build a toilet.

Lat said he had been denied other home improvements as well, saying he couldn’t fix the coconut tree branches serving as a roof for his pig pen, making it harder to raise animals.

“Apsara authorities should protect temples near the compound and let villagers live as normal. Why are they guarding villagers’ land too?”

Rean Sokran, 32, who managed to retain her home within a restricted zone in Angkor Thom district’s Leang Dai commune, said she was punished for making improvements to the roof of her duck coop, also made from coconut tree branches.

“I have asked them and [Apsara authorities] allowed me to build it, but then another group [of Apsara patrollers] came to remove it,” she said.

Apsara Authority’s Kosal denied that conservation authorities have impacted people’s livelihoods, instead saying they are implementing the law in protected zones, he said.

“We do not restrict villagers but the important thing is whether their requests comply with what we can give permission to,” he told CamboJA News over the phone.

“They need to submit a permission [letter]. But if they didn’t submit a proposal and they were secretly building without permission, we call that illegal construction,” Kosal said.

Residents told CamboJA that they submitted permission requests to local authorities, rather than Apsara itself, as Kosal suggested. But when asked about it, the Aspara official said residents should know better.

Kosal admitted that they had some delays in filling responses because of unspecified technical issues, but he said residents should expect faster responses now: “We have now restarted our work [request process], and we have seen more inspections, and a lot of people have received permission to repair following their requests.”

Local Authorities Overruled Regarding Community Resources and Infrastructure

The village chiefs in two separate communes said that even though they were allowed to remain in place, they were denied the chance to build new infrastructure for their communities.

Plang village chief Thoeung Kosal said he requested to fix a shared community house in the Leang Dai commune village but it was rejected in September last year, because the Apsara Authority planned to plant trees in that location.

“Even setting up drainage needs approval from Apsara authorities,” he said, wondering what changes he would be allowed to make for his residents. “Road construction in particular has been denied so we dug up [a road] by hand without using machinery.”

Huy Hak, the deputy village chief of Ampil commune’s Kork Chan village, had similar experiences, saying his request to build new cement roads were either denied directly, or would go several months without hearing back.

“To do something requires permission [from Apsara]. If you plant corn in a rice field or put fencing near a palm tree, Apsara will remove it,” he said. “On behalf of [local] authorities, we want to see villagers have better livelihoods and ask that Apsara authorities ease [the restrictions].”

In Kongchet, a supervisor for the NGO Licadho who monitors the ongoing lawsuits against Angkor temple complex residents, said the people rely on land to feed their families and earn income. Denying them the chance to improve their homes and farmland is a violation of their house and ownership rights, he said.

Kongchet believes the restrictions being implemented by Apsara authorities is a strategic way to push families out of the area.

“It makes the [villagers] feel angry. They thought they were living on their own land but they can’t do anything and have no rights to manage it.”

Apsara could be more considerate of residents’ rights by reducing the area of temple preservation zones – he suggested around 400 to 500 meters around the temples.

But residents say remaining on the land largely sounds better than accepting land in relocation villages, which are limited in plot size, infrastructure and opportunities, according to those who live there.

Chambak village chief Leam Bunloeung said 276 families – almost the whole village in Rolous commune – have had issues with Apsara authorities related to making additions and repairs to their homes, causing some families to move into each other’s houses.

“Honestly, we [villager chiefs] love villagers like our own children. But we can’t make decisions that [override] Apsara authorities,” he said.

The solution offered by Apsara authorities, he said, is that younger married couples can move to government-prepared relocation sites in Run Ta Ek or Peak Sneng.

Those who relocated to Run Ta Ek have protested their lack of arable farmland and insufficient compensation under the government’s social security program IDPoor. Run Ta Ek’s population has also declined by more than 450 families between October and November, according to documents obtained by CamboJA.

“It has declined because they [some leaving] don’t have permanent jobs for them to live there,” said Chhoun Im, the village’s commune chief.

The conditions are no better in Peak Sneng, said Nat Toy, a 44-year-old resident, who already lived in the village and lost some of her ricefield to make way for relocated residents. She previously had 1.3 hectares, and now she can’t grow enough rice to survive on her reduced plot of 20-by-30 meters.

“We are upset [to receive smaller land] and we don’t have rice fields to cultivate,” Toy said.

Instability in Family Homes

A common issue expressed by families that spoke with CamboJA News is that residents don’t know if they can plan for the future, especially when it comes to extending family homes as their children build their own families.

Yan, 45, says her children are not yet married, but she one day hopes she could build additions to their home so they could live together, but with added space and privacy. She now believes that dream is impossible.

“It is very restrictive. Even when we added a one-meter front structure, they ordered us to take it down because they claim it affects Angkor,” said Yan, who asked to use only her given name to avoid repercussions. “We have asked permission but they deny even building a chicken coop.”

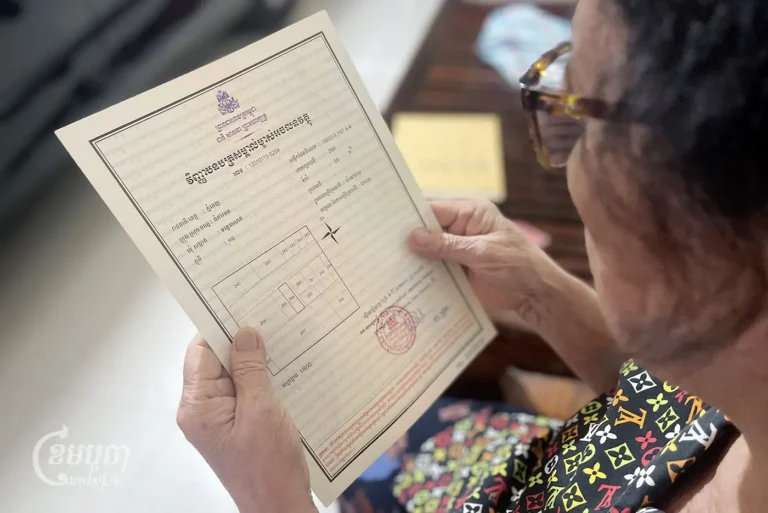

Yan said she would like to apply for a “hard” land title – registered with the national government – to guarantee her right to stay, but that is impossible because her home happens to be in the conservation zone protected by Apsara. But she claims her family had lived there since before the land was designated part of the temple conservation zone, and thus should be granted to her under Cambodia’s Land Law.

“I am upset that we have been living in the old village but they still do not tolerate us,” she said.

“I want to meet with Unesco and ask them why villagers in the old area cannot build houses. I want them to explain this because the government has said the problem comes from Unesco.”

Polina Huard, a press officer for Unesco, wrote in an email that the management of Run Ta Ek is the sole responsibility of the Cambodian government and Unesco has no decision-making role on this subject.

She said Unesco has repeatedly and publicly recalled the importance of “full respect for human rights, as well as urged them to ensure that any relocation is voluntary” since the Cambodian authorities announced their population relocation programme in 2022.

But for Map, the villager living 20 kilometers out from the Angkor temple complex, she feels there’s no action she can take to improve her livelihood without triggering authorities’ reactions.

“I understand that the country has laws but when villagers have asked for permission, they should tolerate us,” Map said. “Nowadays, if you are not allowed to have a house to live in, where can we go?”