The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) in Cambodia has launched a report on March 8 outlining issues arising from the resettlement of evicted communities in the country.

Pradeep Wagle, the representative of the High Commissioner for Human Rights in Cambodia, said via email that the report is one of the most in-depth qualitative studies on the impacts of eviction and resettlement in Cambodia, following several years of consultations with 37 communities resettled to 17 different sites.

“The main challenge reported by evicted communities is that the places they are resettled to are not fit for purpose,” he said. “They are frequently far away from sites of education, work opportunities, and healthcare or are not connected to amenities such as water and electricity.”

He added that there were intermittent consultations between the government and the communities prior to eviction.

The study also contains draft resettlement guidelines recommending steps the government can take to ensure that human rights are fully protected in the resettlement process, avoiding forced evictions and substandard standards of living. OHCHR hopes that the guidelines will be adopted by the government.

Credit Union Foundation Australia (Cufa) was contracted by OHCHR to conduct the research and data collection for the study from 2019 to early 2020. There were 2,341 households across the 17 resettlement sites in Phnom Penh and eight other provinces.

The report illustrated a worrying trend that evicted communities were sent to resettlement sites before infrastructure and services, in particular provision of portable water, sanitation, food security, roads, electricity, health and education services, were in place.

However, it also revealed that most of the relocations were forced evictions—that the resettled households faced coercion and intimidation before, during, and after the evictions, and were not provided sufficient notice and therefore had inadequate time to prepare for their relocation.

Resettlement left households economically worse off, with households reporting increased debt, irregular incomes, and a decrease in sufficiency of income compared to their previous locations.

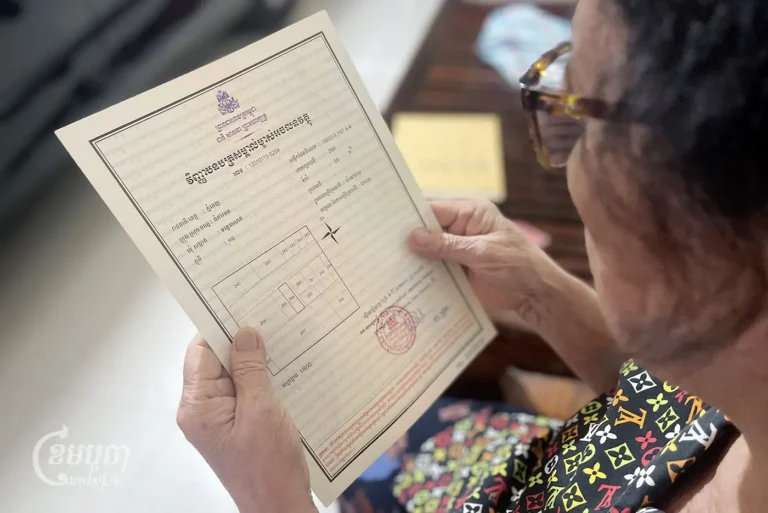

In addition, according to the study, “There are resettled households that currently face difficulties with security of tenure, as they do not have hard land titles, despite residing in the resettlement site for more than five years.”

The study also highlighted problems involving communities in Stung Treng province, where thousands were evicted to make way for the 400-megawatt lower Sesan 2 dam, and Koh Kong province, related to development by the Union Development Group, a Chinese firm. In their resettlement to new locations, they were not provided an adequate standard of living.

The lower Sesan 2 dam, completed in 2018, ultimately resulted in the displacement of nearly 5,000 people—mostly indigenous and other ethnic minorities such as the Bunong and Brao, who have lived in the villages along the Sesan and Srepok rivers for generations. The dam also impacted tens of thousands of other people upstream and downstream from it, according to a Human Rights Watch released last year.

Sea Bunsareth, a 32-year-old from the indigenous minority Bunong group, complained that after being relocated he had insufficient land for food cultivation.

“The company promised to give 5 hectares of rice fields, but I received only 2 hectares and I don’t know where to complain,” he said.

He added that the infrastructure in the relocation site was about 90-percent completed, including roads and electricity, but that the water wells are of bad quality and cannot be used.

Svay Sam Eang, Stung Treng governor, rejected the study, saying that it doesn’t reflect government policy, and that the government has made an effort to resolve the people’s issues.

“It is usually the case that investment has always had an impact, but we made an effort to resolve it through the government policy,” he said.

“I think that the government had resolved properly, but I don’t understand whether people have not been resolved about what they really wanted,” Sam Eang said.

He said that the government has provided advantages to the relocated communities that they didn’t enjoy in their old locations, offering houses, land, and other amenities.

“If they demand too much, we can’t resolve.Normally, we can’t satisfy all people,” he said.

Sok Sothy, Koh Kong provincial deputy governor, declined to comment on the report. (Additional reporting by Kheang Sokmean)