A number of families affected by the new airport project in Kandal province have continued to block the road after a week of protest. Dozens of people have protested since Friday last week after the company developing the multi-billion-dollar project used tractors to clear their rice crops, damaging more than 1 hectare of rice fields.

Kheang Sokmean, a representative of those affected by the development, said that about 50 people have remained on stand-by at the disputed land during the daytime. At night, ten people stand guard to protect their land.

“For a week, no authorities or company representatives have come to talk with us, and they are acting like nothing happened,” he said. He added that community members were discussing the possibility of seeking help from human rights groups or UN agencies in Cambodia.

“We will not be seeking any intervention from government institutions anymore, because we already submitted a request to them, including a petition to Prime Minister Hun Sen,” he said. “In this phase, we do not put our hopes in the authorities — we will seek help from human rights groups to help put more pressure on the authorities.”

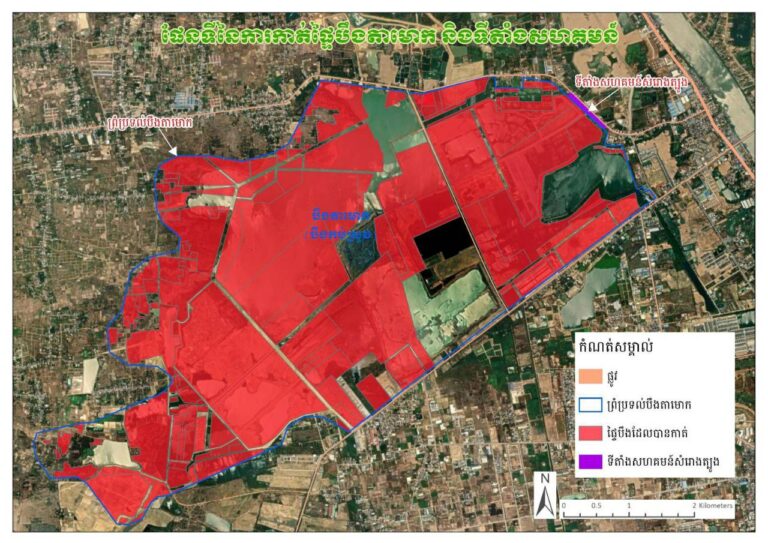

The conglomerate Overseas Cambodia Investment Corp (OCIC), which is overseeing the $1.5 billion project alongside the government’s State Secretariat of Civil Aviation, has been repeatedly accused of encroaching on people’s land. The development covers 2,600 hectares in Kandal Stung district, Kandal province. The airport project’s first phase is set to be completed by 2023, with the company preparing for as many as 30 million passengers a year by 2030.

So far, the company has reportedly offered people affected by the development $8 dollar per square meter of their land. Many have refused, leaving the dispute unresolved since 2019.

Kandal provincial governor Kong Sophorn said that hundreds of families had already accepted the compensation and supported the government’s development project, while some other families kept demanding a higher price.

“We offered them a good option; we implore them to accept the offer, and we never threaten them,” he said. “If they do not accept the price, we can reserve land in another place nearby for them, but they still will not accept.”

Sophorn said the government could not go higher than what they had offered.

“They don’t think about the solution, but instead they are seeking intervention from NGOs,” he said. “They normally do this rather than finding a solution, but this is within their rights to do.”

The UN’s newly appointed special rapporteur to Cambodia, Vitit Muntarbhorn, who replaced Briton Rhona Smith after she had completed her five years mandate, has yet to make any comment on Cambodia’s human rights situation since he was officially appointed in March.

Vann Sophath, business and human rights project coordinator at the Cambodian Center for Human Rights (CCHR), said that people locked in land disputes or facing human rights abuses always seek help from NGOs when those issues are not resolved.

“They have the right to seek intervention from all parties,” he said. “As NGOs, we can only provide them with consultation support, legal assistance and make recommendations to the government to provide them with an acceptable solution and respect their human rights.”