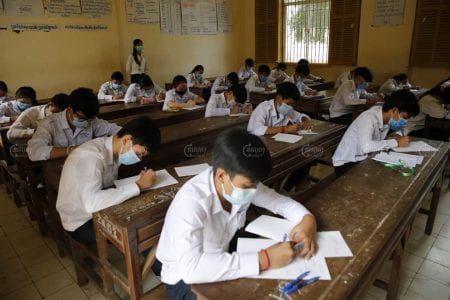

As students try to fully return to the routine of a standard school year, experts are beginning to trace the full impact of nearly a year-and-a-half of distance learning.

Experts say student learning outcomes have been significantly hurt by prolonged school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Most notably, the lack of traditional schooling during the pandemic has reduced access to education for certain groups of children, especially those living in remote areas and coming from poor families.

Pointing to these conclusions, the World Bank and Global Partnership for Education on January 18 announced a new line of financing to make available $69.25 million dollars for educational development in Cambodia. A joint statement from the organizations said the bank will provide a $60 million credit through its International Development Association while the education partnership will deliver a grant of $9.25 million.

The statement said this funding will be used to support the kingdom’s five-year General Education Improvement Project (GEIP), aiming at supporting Cambodia to achieve its goals in establishing and developing the highest quality human resources in order to develop a knowledge-based society. The statement also said the Cambodian government has committed to addressing low student learning outcomes and inequitable access to quality education.

Education Ministry spokesman Ros Soveacha told CamboJA the ministry welcomes and appreciates the cooperation of the private sector and development partners including the World Bank in helping to improve the quality of education and strengthening health and safety for teaching and learning during the COVID-19 era. However, he declined to comment on how the ministry will implement the project.

The joint statement from the funding agencies also did not specifically discuss implementation.

Maryam Salim, the World Bank’s Cambodia country manager, said in the statement that the funding would focus on students most vulnerable to leaving school, such as those living with disabilities or who come from poor or ethnic minority families.

‘’We strongly hope that the project will address these challenges and build back better,” she stated.

The statement said there are several activities that will be implemented in the project, listing programs in school-based management, improved learning environments and capacity development for teachers, school leaders, teacher trainers and educational staff.

UN agencies such as Unicef have already flagged extended school closures as a significant potential stressor for school-aged children. According to a Unicef report released last June, prolonged school closures can greatly impact not only students’ learning abilities, but also their physical and mental health.

Cambodia first closed all private and public educational institutions across the country in March 2020, at the onset of the pandemic, until November of that year. Schools reopened then for a few months but were closed again after a period of community transmission referred to as the February 20 event, which began the ongoing viral outbreak. The government began a large-scale school reopening at the start of November amidst the outreach of the country’s mass vaccination program.

Still, education-oriented international development agencies such as Unesco say that even when schools have reopened, it is still difficult to ensure that children and youth will return to and remain in class.

Unesco states in its global COVID-19 educational response that economic hurdles may keep children out of school. Along with long-term closures, the UN agency has written that “economic shocks place pressure on children to work and generate income to financially distressed families.”

According to the Education Ministry, in the 2019-20 school year, the dropout rate for primary school students had increased to 6.8 percent, compared with 4.4 percent the previous year.

For lower secondary school students in grades 7-9, the dropout rate increased from 15.8 percent to 18.6 percent. The dropout rate for upper secondary grades 10-12 during that school year remained unchanged at 16.9 percent.

Daniel Schmücking, country representative of political think-tank Konrad Adenauer Stiftung Cambodia, said school closures were especially difficult for students who did not have access to digital devices to follow online teaching. At the time he said, teachers had also not been trained to teach online.

‘’Unfortunately, until these days, some schools and universities remain closed and continue with online classes,” he said. ‘’As Cambodia is opening up, it is very important that schools and universities will resume physical classes soon, allowing students to catch up with what they have missed in the pandemic years.”

Ouk Chhayavy, president of the Cambodian Independent Teachers’ Association, told CamboJA that inequitable access to education had been an issue before the pandemic and only worsened over the COVID-19 years.

‘’Students, especially those living in remote areas face plenty of difficulties during online learning,” Chhayavy said. “With that, the shortage of digital devices and poor internet connection are the two main problems that they have encountered.”

Rochom Samoeun, a teacher at Takokphnorng primary school in the O’yadav district of Ratanakiri province, said that even when in-person classes return, students mostly from ethnic minority communities still find it hard to get back to school as they need to help their families with farming.

‘’Their parents do not really support them to prioritize their studies but ask them to help with their work instead. For example, as of now, most of the students are absent because they need to help their parents harvest crops,” said Samoeun. “Because of these reasons, some students possibly decide to drop out of school when they cannot catch up with the lessons.”