Students with disabilities still struggle at Cambodia’s private universities, which are failing to meet their needs, and the country does not have any specialized colleges for the disabled despite the government’s National Strategic Plan on Disability – which aims to make access to education easier for people living with disabilities.

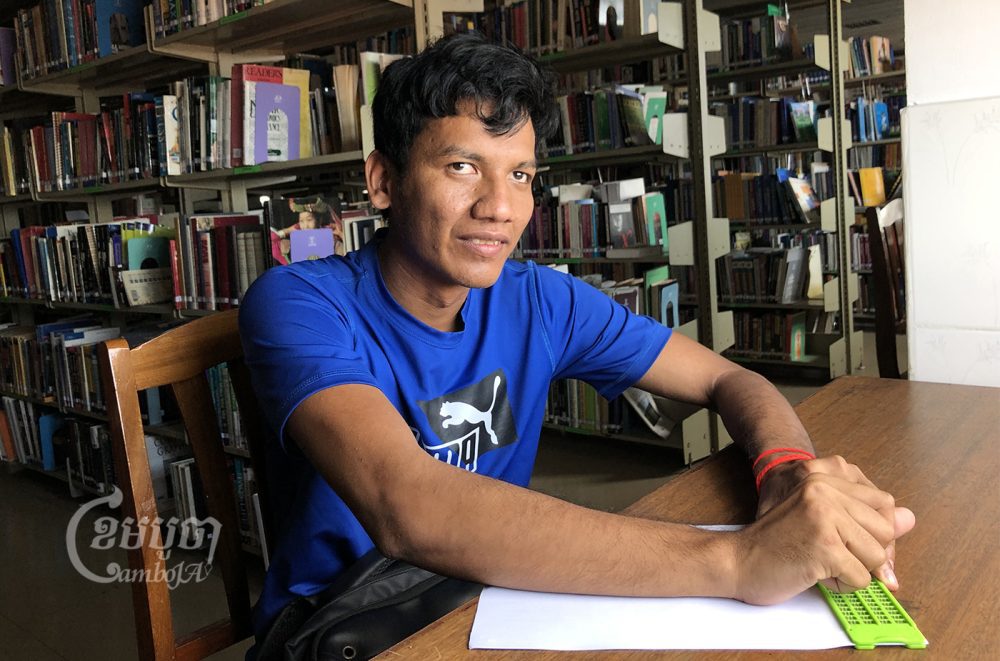

Mey Ponlok, 25, is a second-year student majoring in international relations at a university in Phnom Penh and has been blind since birth. He told CamboJA that everything about his day is hard, from getting to classes and following lectures to lack of reading materials in braille.

He said there are no research materials available at the university for blind students, who have to ask for books to be converted into braille at the Institute of Special Education – a process that takes weeks.

“There is no braille at school. So if I want to read books, I need to get them converted to braille. This takes time and slows down our learning,” he said. “Sometimes the mid-term exam is over by the time I finally get a book to read.”

Then in class, he said, blind students can only listen, explaining: “our learning is different from other students’ and our reading is slower…. They use their eyes and ears, but we only use our ears.”

Getting to lectures is also a daily struggle, Ponlok said.

“I want all relevant parties to facilitate the daily expenses and means of travel because we cannot travel anywhere on our own and have to rely on others to deliver or call a Tuk-Tuk. It costs a lot,” he said.

Ponlok comes from a poor family and received a 100% scholarship for college. However, it only covers classes and not living costs, so he lives with a group of more than 30 students in Phnom Penh and each student contributes $10 per month towards daily expenses.

Still, he says, he knows it’s vital to get an education, even if it might be hard to find work after university.

“Even if we have a bachelor’s degree and a low percentage of employers, we can share this knowledge with the community and educate ourselves,” he said.

So Siem Sokhim, 25, who is also a blind student majoring in international relations, said he was no different from Ponlok. He faces three major challenges: traveling, in-class learning, and exams.

“When we started college, there were no books for the disabled like in our special education classes at high school and primary school,” he said. “Though we all also use technology to learn, it’s not 100% effective.”

He said at least during exams the college allows him to take an oral test.

Like Ponlok, he’s worried about what he’ll do when he completes his studies, believing after graduation it will be difficult to get a job.

“People with disabilities are encouraged, but very few blind or deaf people can be involved in public or private work,” he said.

Education Ministry spokesman Ros Soveacha said that disabled students at two universities, the Royal University of Phnom Penh and Kamchay Mear University, receive $50 per month from the university, and that female students are provided with free accommodation. The Union of Youth Federations of Cambodia also contributes $10 per student per month.

According to Sovacha, there are currently 43 students with disabilities who are studying for undergraduate degrees, including 13 women, and last year, eight students with disabilities graduated. He said the ministry helps such graduates to find jobs.

“The Ministry has proposed a policy that would see 70% of graduates gain work as special teachers for other students with disabilities, 15% to work with development partner organizations, and the other 15% to work in ministries and government institutions,” he said.

He continued that in order to help students with disabilities study at the college level, the ministry would seek to reduce the cost of the necessary documents and study materials they need.

Chhor Ponnarath, program director at Cambodian Disabled People’s Organization (CDPO), said that the blind have the most problems with college education because private schools do not seem to take them into account, especially regarding reading materials. University lecturers also have no training in how to teach these students, he added.

“Very few teachers have received training in how to teach the blind. The university doesn’t think about the blind students who must attend college,” he said.

He said that CDPO always advocates for the government and the National Employment Agency to help disabled people who have an education and skills to get jobs.

He added that the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Social Affairs are working together to develop a strategy to enable people with disabilities to get the same level of education as non-disabled people.

“We already have a law that deals with the blind getting the same education as the non-disabled. We have this law and we must push this law to actually work,” he said.