A quantitative study of microloan debt in Kampong Speu province published Tuesday by two human rights NGOs highlights the impacts of “widespread overindebtedness,” including coerced land sales, child labor and families limiting their food consumption.

“This research adds further evidence that human rights abuses are occurring frequently and systematically in Cambodia’s microloan sector,” said Naly Pilorge, outreach director of Licadho, which produced the report along with Equitable Cambodia.

More than two-thirds of borrowers believe their households hold too much debt, the study found. The study estimates upwards of 80% of the province has at least one microloan.

Around 27% of families in the study — which would indicate around 43,000 families across the province — spent more than 70% of their monthly income on debt repayment. This is a violation of widely used international client protection standards which the Cambodia Microfinance Association and Association of Banks in Cambodia, representing the sector’s largest financial institutions, mandate their members adhere to.

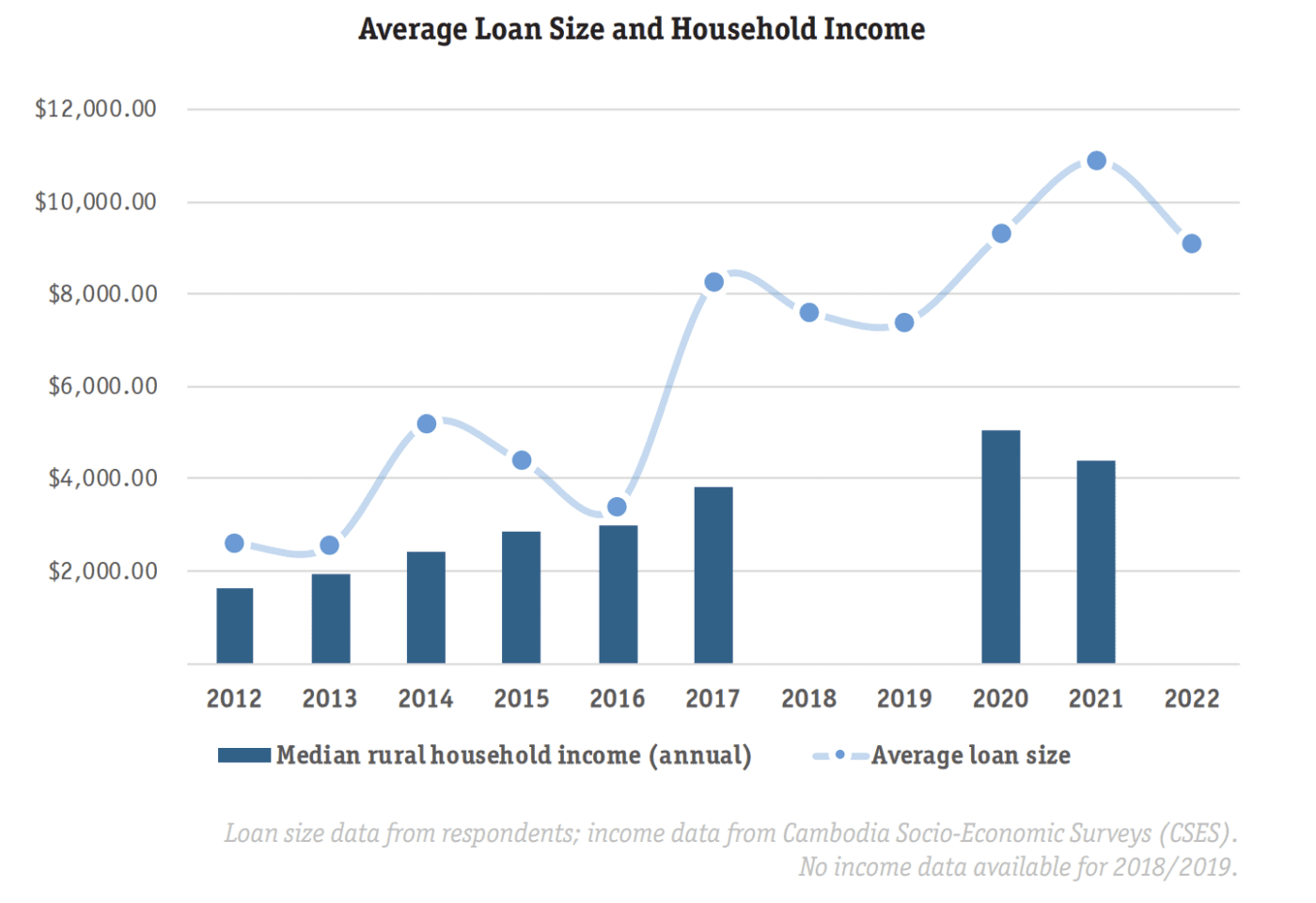

The average loan size from 2022 is just over $9,000, while the annual median income in rural areas of Cambodia is $4,381 as of the latest available data from 2021, the study reported.

CMA spokesperson Kaing Tongngy said the CMA needed to “study the report in detail” before providing comment.

“However, ‘client protection’ has always been the industry commitment to ensure the sustainability of the sector,” he said in a Telegram message.

Microfinance institutions and commercial banks receive millions in funding from Western development banks to provide microloans to families to improve their livelihoods through funding agriculture and small businesses. Since 2019, Cambodia’s microloan portfolio has doubled from $8 billion in debt to $16 billion in debt across 2.89 million loans, the study reports.

But in recent years the Cambodian microloan sector has come under scrutiny for causing debt-driven land sales, migration and other harms to borrowers.

In August, the International Finance Corporation’s (IFC) ombudsman opened an investigation into six of Cambodia’s biggest microlenders and four financial intermediaries, stating it had found “preliminary indications of harm” to borrowers and possible violations of IFC environmental and social standards. The investigation was prompted by a complaint filed last year by Licadho and Equitable Cambodia alleging “predatory and deceptive lending practices.”

While Licadho and Equitable Cambodia had previously published several studies documenting borrowers experiences of over-indebtedness, qualitative NGO reports were often dismissed on the grounds the research was not “statistically representative,” the NGOs’ report states.

The new research, conducted by an external research team, surveyed more than 700 households across every district in Kampong Speu “through a random sampling process.”

The study found that 18.3% of respondents — nearly 30,000 families — said they were eating less food as a result of their microloans or around 28,800 families across Kampong Speu’s 195,882 households.

In 3% of households — 4,565 across the province — children dropped out of school to help their families repay microloans. All of the sector’s largest microlenders were implicated in providing loans which led to children dropping out of school, according to the study.

Most families took out loans to build or repair a house or else invest in business. Yet more than a third of borrowers say they were using microloans to repay other loans, a practice described as “debt cycling.” This represented a significant increase from a study in 2012 which found only 3.45% of borrowers were using loans to repay other debt.

However, the study also found that 38.6% of borrowers felt the loan had increased their income and 45.5% reported no affect on their income, while 15.9% reported decreased income.

Around 6% of families — or about 9,600 across the province — reported selling land to repay a microloan, echoing similar findings from a German government-sponsored quantitative study published in August last year, which indicated 6.2% of microloan borrowing households nationwide — 167,000 families — sold land to repay debt in a five year period.

While University of Hamburg development anthropologist Frank Bliss, the lead author of the German government-funded study, has claimed the negative consequences of microloans are due to unethical credit officers, the NGOs’ study counters that “debt-driven land sales…are an inherent characteristic of Cambodia’s microfinance sector.”

More than 92% of households in the Licadho-Equitable Cambodia study said they provided land titles as collateral for their microloan, close to the 82% of microloans nationwide are collateralized with land titles, according to the Credit Bureau of Cambodia. The Cambodia microloan sector has been criticized for relying on the value of land used as collateral as opposed to providing loans based on a borrower’s capacity to repay from existing and projected income.

Microloans were not intended to rely on collateral, according to Nobel Peace Prize winning economist Muhammad Yunus, who pioneered the concept of microfinance and argued that loans “without collateral” are more accessible and safe for the poor. The Reserve Bank of India, overseeing one of the world’s largest microfinance sectors, defined microfinance loans as “collateral free” under revised guidelines issued last year.

In Channy, president of ACLEDA Bank, which holds a large microloan portfolio, said that the “main principle” for microloans is “lending against cashflow” from the borrower’s business activities. But he defended the Cambodian microloan sector’s widespread use of land titles as collateral and said it was allowed under existing government laws, while noting alternatives for borrowers to use as collateral such as “cash” or “gold” or “equity.” He did not respond to the study’s other findings.

The study also found most borrowers did not understand the legal process of loan default and believed local authorities or microlending institution’s credit officers could seize their land if they failed to repay. In reality, a microlending institution must sue the borrower in court to seize their land in the event of a loan default.

The study calls for “current and recently exited investors” in Cambodia’s microfinance sector to “take immediate action to remedy the harms they have contributed to” including through “debt relief and proper compensation for borrowers who suffered human rights abuses as the result of predatory microloans.”

“These harms have now been revealed in detail, with both qualitative and quantitative methodologies, over the past four years” said Eang Vuthy, executive director of Equitable Cambodia. “Investors, authorities and development actors need to take immediate steps to enact remediation for borrowers and ensure these predatory practices stop, and put in place necessary consumer protection regulations so that we can ensure borrowers’ fundamental human rights are respected.”

Association of Banks in Cambodia Chairman Raymond Sia, who is also CEO of Canadia Bank, said in a Telegram message that “the issue of ‘over indebtedness’ is not a new issue and all parties need to be mindful that both the lender (MFIs/Banks) and borrower have an important role to play.”

“It is important that the MFIs/ Banks need to continue to educate and increase financial literacy in-country and re-inforce “responsible banking” in their employees; which includes responsible lending, responsible deposit-taking and responsible collection / loan recovery,” Sia said. “Concurrently borrowers need to ensure they seek clarification if they are uncertain on the loans and obligations they enter-into and avoid being coerced into entering into loan agreements they are not familiar with.”

Sia noted that the Association of Banks in Cambodia and the Cambodia Microfinance Association had on Tuesday launched a new standard loan agreement providing “uniformity on loan agreements” intended to “make it easier” for lenders to explain loans to customers.

The German government has been one of the Cambodian microloan sector’s largest investors, including through two microfinance investment funds being investigated in the same IFC complaint. A spokesperson for the German government’s Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development said in an emailed statement that it is “studying the results of the report” and “takes the issue of microfinance-related overindebtness very seriously.” The spokesperson also noted that a meeting with Licadho and Equitable Cambodia is scheduled for September and “the results of the study will surely be discussed comprehensively.”

CMA Chairman Sok Voeun, who is also the CEO of LOLC Cambodia, declined to provide a comment because he was busy.

AMK Microfinance Institution’s Legal Manager Chhe Sao Elen said AMK will “look further into the detail” of the report and noted that approximately 74% of AMK’s loans did not use collateral and were capped at around $1,000 per individual.

Representatives from five of the Cambodian microloan sector’s other largest lenders, Sathapana Bank, Hattha Bank, Amret Microfinance Institution and Prasac Microfinance Institution did not respond to requests for comment.

National Bank of Cambodia Governor Chea Serey did not respond to requests for comment.

Update: This story has been updated to include comments provided by Association of Banks in Cambodia Chairman Raymond Sia, AMK Microfinance Institution and the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) after publication.