The farmers of Knong Riel run when they see white faces.

A white face, for many farmers, means staff from Wildlife Alliance, one of Cambodia’s leading conservation NGOs, have entered the northern edge of the Cardamom National Park where dozens of families grow cassava, corn and other cash crops. The contested stretch of land, in the northwestern province of Pursat’s Phnom Kravanh district, is known locally as Knong Riel.

Farmers there say Wildlife Alliance rangers, accompanied by armed camouflage-clad Environment Ministry officials and military police, confiscate motorbikes, slash tractor tires, shred bags of harvested cassava and destroy homes and shelters. A Wildlife Alliance patrol also allegedly beat up a villager.

Most of the dozens of families farming at Knong Riel are using land classified as protected conservation area, making their activities illegal. Wildlife Alliance says these farmers have contributed to hundreds of hectares of deforestation in the past six years. The farmers say the patrols lead to unrelenting abuse as they try to eke out a livelihood in an already degraded forest landscape.

“We are so scared living here, but we have no place to go,” said an older woman, Sinn, who requested a pseudonym be used because she farms a small plot of cassava inside the protected area. “We do not really have enough time to plant the crop because most of the time we run into the forest to escape from the officials. If they see us, they arrest us.”

Wildlife Alliance began patrolling Knong Riel and other sections of the park in Pursat in late 2019. Over the next two years, Environment Ministry and military police units, alongside the NGO’s staff, demolished and in some cases burned more than 55 structures at Knong Riel — which farmers said were their permanent homes — while evicting upwards of 85 families living or using land in the area.

Images of what Knong Riel farmers say were their homes, destroyed between 2019 and 2021, by Wildlife Alliance and law enforcement authorities. (Supplied)

More than a dozen farmers shared testimony of Wildlife Alliance’s involvement and tactics, and farmers sent at least eight complaints to officials and a human rights NGO detailing alleged abuses since 2019. Last year, they also filed a complaint to the Pursat provincial court against Wildlife Alliance staff, the Environment Ministry and provincial and district authorities, including photos of demolished and burned homes. A government official with the Supreme Consultative Council, an oversight body which often reviews land disputes, visited Knong Riel twice shortly after home and crop destruction and wrote up a scathing 2021 report, obtained by CamboJA, implicating both Wildlife Alliance and the Environment Ministry in causing “serious damage” to people’s lives and livelihoods.

Since then, little has changed: the boards of Sinn’s hut — she no longer dares to build a proper home — were blackened from when rangers set it on fire in early January, she told CamboJA several days afterwards.

“They burned the plastic tent roof of my hut. They confiscated the weed cutter and spray machine which I bought using money from a microfinance loan. And they even poured the rice out of the container to the ground. I have nothing to eat,” said Sinn, in tears, the remains of scattered rice grains still visible in the dirt around her.

The ranger patrols’ ongoing crackdown against impoverished farmers like Sinn highlights broader inequities of law enforcement practices in protected areas, and reveal conservation groups’ conflicting approaches over how best to engage with people inside or adjacent to the national park.

The nearly one million hectare Cardamom National Park, created in July, combined and expanded two existing national parks linked to two NGOs: the Wildlife Alliance-led Southern Cardamom mountains and the Central Cardamom mountains, encompassing Knong Riel. The Central Cardamom protected area has long-standing ties to the NGO Conservation International, which established a financial trust for the Central Cardamoms and is listed as the Environment Ministry’s official NGO “partner” in a recent grant for the area from a German and French-government-supported fund.

Conservation International Cambodia director Sony Oum said his organization was founded as a “rejection of fortress conservation” such as the militarized patrols used by Wildlife Alliance to intensively enforce park boundaries.

“The allegations made against Wildlife Alliance are in direct opposition to the mission of Conservation International,” Oum said in an emailed statement.

But the law enforcement operations in Cardamom National Park are working exactly as intended, according to Jeff Morgan, a former tech executive who runs the San Francisco-based NGO Global Conservation, partially funding Wildlife Alliance’s ranger patrols in the Central and Southern Cardamoms.

“We call them invaders,” said Morgan, of the Knong Riel farmers. “Having their houses burned down, that’s unfortunately a big part of the job. …Mostly, it’s just the male and the son out there and they start cutting the forest.”

“Thank God someone’s enforcing the laws,” he added.

Despite claiming to disavow home burning, Conservation International acknowledged Morgan provided 12% of its protected area management budget for the Central Cardamom Mountains National Park between 2019 and 2022.

Wildlife Alliance head of ranger operations Eduard Lefter said his NGO was merely assisting authorities to enforce Cambodian law and denied there had been abusive patrolling tactics. Like his Environment Ministry counterpart in Pursat, Lefter claimed patrols only dismantled huts and tents.

“People come up with all kinds of stories about Wildlife Alliance, we don’t get into these small details because it loses our time,” Lefter said. “I strongly believe that they [Knong Riel farmers] will blow up stories just to make Wildlife Alliance look bad.”

Allegations of human rights abuses linked to Wildlife Alliance have emerged in other protected areas where the NGO operates. Human Rights Watch has stated it is investigating alleged abuses in the Wildlife Alliance and Environment Ministry-run Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project, which sells carbon credits. REDD+ accrediting organization Verra suspended the project in June as a result of preliminary findings from Human Rights Watch and opened its own investigation. Human Rights Watch declined to comment and Wildlife Alliance has denied abuses there.

Wildlife Alliance has “a heavy emphasis on law enforcement and territorial control,” said Sarah Milne, a former Conservation International employee and a conservation researcher at Australian National University who has worked for more than two decades in the Cardamom Mountains.

“Law enforcement in Cambodia targets powerless people and it favors vested interests and the ruling elite,” Milne added. “The weak and the vulnerable are the ones that cop the violence and are the ones that get the raw deal when law enforcement happens.”

Flames and Destruction

Boran remembers his four-year-old daughter crying as a team of rangers, including a foreigner working for Wildlife Alliance, destroyed their home in 2020.

“They told us about a week before to leave, but we didn’t have anywhere to go because we don’t have any land,” he said, adding that Wildlife Alliance staff identified themselves during these encounters.

When the rangers came back, he and his wife watched as the NGO and authorities descended on their farm. Their personal possessions were removed, and then the rangers poured gasoline on the dismantled home and set it aflame, according to Boran, who requested a pseudonym for his safety.

The foreign Wildlife Alliance employee gave their little girl a 50,000 riel note or about $12.50 in compensation, as her home went up in flames, Boran recalled with a bitter laugh.

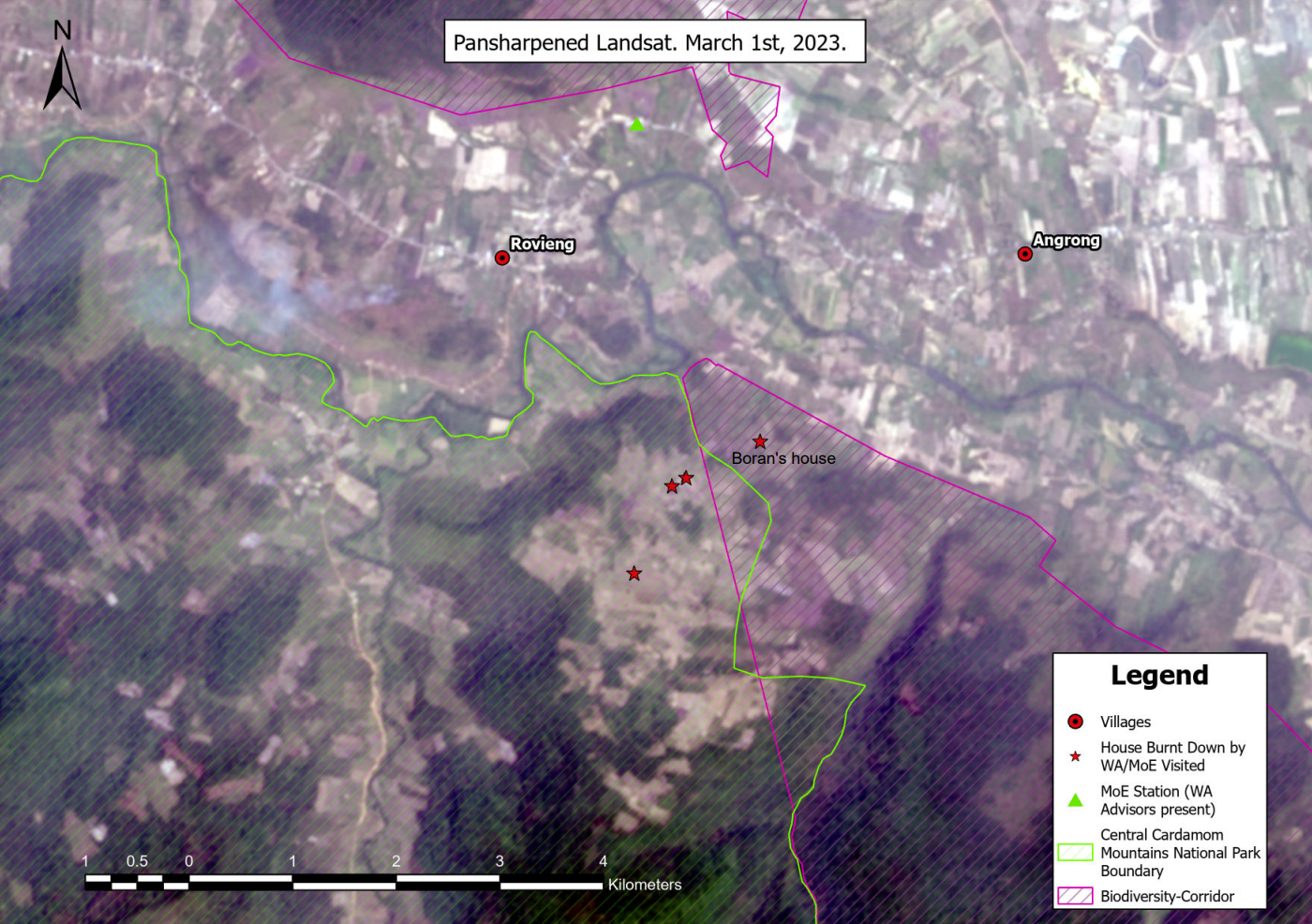

Though most of the farmers had built homes inside the park, the GPS coordinates of the remnants of Boran’s home — a mangled tin roof, posts cut with what appeared to be a chainsaw, and burned wooden planks — show it was outside the park’s boundaries at the time it was destroyed. In 2017, the area where he had built his home was classified as a biodiversity corridor, and was only folded into the national park as part of its July expansion.

Boran, who is originally from a village near Knong Riel, previously took out a loan to apply to work in Thailand but said he was cheated out of his money by a broker. He decided to turn to farming instead and built his family’s home in Knong Riel in 2016. He admitted cutting down trees to do so, but said it was only to cultivate cassava to support his family and that local authorities appeared to look the other way at first.

After Boran’s family lost their home in 2020, they did not leave the area. Boran and his wife still farm there, sleeping on wooden planks under a plastic tarp with their two young daughters. Their shelter has been repeatedly burned down by ranger patrols and in December, their clothes and other possessions were again set on fire, he and his wife say. Charred pink children’s crocs lay in the grass in March.

Rangers have also arrested people like Khim Hoch, a single woman in her 60s, who served six months in prison after being caught inside Knong Riel by a patrol in April 2021; she says it included Wildlife Alliance staff. Hoch, her village chief and other farmers say she was working as a hired laborer to help with cassava harvesting when officials arrived and claimed she had been involved in illegal logging.

Hoch, who is blind in one eye and lives on a small patch of land 30 minutes from Knong Riel, said she had been picking cassava inside the protected area to support her young nieces while their mother labored in Thailand. She was charged with illegal forest clearance, according to court documents obtained by CamboJA.

“I was crying and begging them [the rangers] that I have not cut any trees,” Hoch said. “I cried the whole night and ate nothing when they sent me to the detention center for the first day. During the six-months in jail, there was not an easy day for me.”

In a case from May 2020, a Wildlife Alliance ranger patrol in Knong Riel tried to arrest Channy, who was pregnant with her third child at the time and spoke with CamboJA on the condition that a pseudonym be used.

She lives in a village near Knong Riel and stays with her grandmother. The family did not have enough land to support themselves so Channy said she began to farm inside the protected area in 2014.

Several rangers carrying rifles and a foreign Wildlife Alliance staffer attempted to arrest her, she and three other Knong Riel farmers said. Soon after, a group of several dozen villagers, armed with machetes and farming gear, confronted the patrol, an encounter partially filmed by both Wildlife Alliance and villagers.

One man, Som Sokha, was later arrested and served two years in prison on charges of obstructing and threatening authorities. Lefter showed CamboJA a photograph of Sokha holding a machete during the incident, but did not comment on Channy or Hoch’s cases. Sokha claimed he had done nothing wrong.

The same month, a middle-aged man named Mon Chhun and his son, in his twenties, were confronted by a Wildlife Alliance patrol, including a foreign ranger. A resident of Angkrong village, Chhun said he told them he was picking wild mushrooms, but then two of the Cambodian rangers repeatedly elbowed him in the face, warning him that farmers in Knong Riel had become too “headstrong.” The rangers checked Chhun and his son’s phones for images to see if they had been involved in illegal activity or the previous altercation with the patrol.

“They handcuffed me and when I tried to move my body, they punched me,” he said. “The foreigner then handcuffed my son.”

Lefter said that “if this happened, the supervisor who was there will be jailed” but noted Wildlife Alliance did not bother to investigate these claims because he was convinced “it didn’t happen.”

The rangers eventually let Chhun and his son go. Soon after, Chhun said he filed a complaint to the human rights organization Licadho, which confirmed it had received the report.

“Licadho has over the years received multiple complaints of overly harsh and at times violent measures taken by Wildlife Alliance and their Cambodian authority counterparts when dealing with settlements within protected areas,” said Licadho Outreach Director Naly Pilorge in a statement. “…Licadho believes the use of violence against Cambodians as an enforcement mechanism is unjustifiable.”

Enforcement: “It’s Ugly”

Wildlife Alliance arrived in Cambodia in 2000, originally under the name WildAid and heavily funded by co-founder and CEO Suwanna Gauntlett’s inherited wealth from the Upjohn pharmaceutical fortune. (Gauntlett declined to directly respond to CamboJA’s requests for comment.) The organization secured much of Southwestern Cambodia for its conservation projects, including anti-wildlife trafficking initiatives, eco-tourism sites and a wildlife sanctuary near Phnom Penh.

Enforcement has always been at the forefront of the NGO’s priorities.

“Giving better livelihoods to local communities is only part of the solution,” Wildlife Alliance’s Gauntlett said in a 2017 press release. “It is vital to take a strong stance and conduct law enforcement to prohibit forest burning, cutting and clearing that are so embedded into the culture of most Southeast Asian countries.”

Wildlife Alliance is likely most famous for its often-glorified ranger patrols. A 2019 documentary, “‘Soldiers of the Forest”, follows a team of military-trained Eastern European Wildlife Alliance staff and military police partners.

Cambodia’s military police, embedded in Wildlife Alliance patrols, are overseen by Sao Sokha, a general implicated in alleged human rights abuses. Elsewhere in Cambodia, Environment Ministry rangers have had their own stations burned down when communities pushed back against their tactics.

“Yeah, it’s ugly, we see the guns, we see the handcuffs, but [at] the same time we see the forest standing,” ex-French foreign legion officer and Wildlife Alliance ranger Ionescu ‘I.D.’ Dragos said in the documentary. “We don’t see trucks full of timber coming out from the forest.”

A foreigner called “I.D.” — Dragos’ nickname — was repeatedly named by farmers CamboJA spoke to in Knong Riel as one of several foreign patrollers involved in the home burnings, the attempted arrest of the pregnant woman, and other tactics they described in complaints as “cruel.” He and other Wildlife Alliance staff are also mentioned in many of villagers’ complaints to authorities. The villagers had learned the identities of the rangers from a neighbor who had once worked as a cook at the nearby ranger station. Dragos did not respond to repeated attempts to reach him for comment, including calls and messages received by his wife on Telegram.

Wildlife Alliance’s Lefter said Dragos left the organization in 2021 for “personal reasons.”

Wildlife Alliance patrols operating in Knong Riel sought to sabotage farmers, whether that meant ripping open bags of cassava, taking their farming equipment or even stealing items like chickens from their homes, villagers say.

Wildlife Alliance’s website emphasizes its leadership role in patrolling with government officials: “We technically mentor and coach government law enforcement staff 24-7 in the field.” Near Knong Riel, Wildlife Alliance staff live at the Rovieng patrol station with their Cambodian law enforcement counterparts.

Pursat Department of Environment director Kong Puthira told CamboJA that his employees receive extra funding from Wildlife Alliance to supplement their $250 monthly salary. He explained this often includes food, transportation costs and bonuses for confiscated equipment as “encouragement.”

Lefter defended Wildlife Alliance’s approach to forest protection, claiming that while the NGO led patrols, its staffers were not in charge of arrests. Wildlife Alliance’s website states that the NGO “fulfills the role of watchdog conducting good governance oversight” and verifies documents prepared by officials for each arrest case.

Wildlife Alliance patrols follow the law to prevent illegal clearing, Lefter added. Deforestation in the 400,000 hectares previously classified as Central Cardamom Mountains National Park increased in 2022 and the area around Knong Riel has been a hot spot of forest degradation.

Lefter showed CamboJA aerial images of dozens of structures and farms in Knong Riel which he said had been built within the last six years and contributed to approximately 1,000 hectares of forest loss. The government oversight body, the Supreme Consultative Council, estimated the clearance was around 500 hectares.

Satellite images indicate that the clearing in Knong Riel began between 2010 and 2011, including at the site of Sinn’s first destroyed home. Additional farms appear to have emerged between 2013 and 2015. Significant clearing occurred through the end of 2018.

“This is illegal land grabbing by villagers,” Lefter said, of the farming at Knong Riel. “If people lived there from 10 years ago we don’t go against them…we can see by satellite image.”

He said that Wildlife Alliance staff were present during the demolition of homes but claimed the “destruction…[was] conducted by provincial authorities” and “who burned [the structures], I can’t tell you, but it was not Wildlife Alliance who does it.” He then added: “This happens everywhere.”

More than a dozen Knong Riel farmers say Wildlife Alliance staff actively participated in evictions and home-demolition, and Wildlife Alliance is named as a party in multiple home burnings by the Supreme Consultative Council’s report and earlier complaints from villagers obtained by CamboJA. The NGO has also been involved in burning structures and equipment, according to other media reports over the years.

The locations of each of the dozens of destroyed houses in images shared by Knong Riel farmers could not be verified independently by CamboJA. But when shown a range of images shared with CamboJA by Knong Riel farmers, Wildlife Alliance’s Lefter confirmed the dismantled structures were from Knong Riel.

In Knong Riel, CamboJA encountered remnants of five demolished structures, several with signs of burning, and four families identified photos of their destroyed homes and homes of neighbors from documents obtained by CamboJA. Government reports and public statements from shortly after alleged home burnings show officials touring the area amidst scorched and collapsed structures.

Images of in-tact and destroyed homes allegedly in the Knong Riel area of the Cardamom National Park; image at top left shows a delegation from the Supreme Consultative Council visiting the aftermath between 2020 and 2021 (Supplied).

The United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights writes that evictions should include “genuine consultation”, “adequate and reasonable notice” and access to legal remedies.

“Individuals affected by eviction orders have a right to adequate compensation for any loss of property and that evictions should never result in individuals being rendered homeless…” the UN Special Rapporteur on Housing states on its website.

Multiple people who had their homes destroyed by provincial authorities and Wildlife Alliance rangers said they were forced to sleep in the forest until they found more permanent shelter.

Lida Leng, Wildlife Alliance’s Cardamom Forest Protection Program coordinator, said that the NGO was not responsible for relocating displaced farmers: “Where to bring them, that’s not our duty.”

A Lack of Accountability

After receiving petitions via Facebook from a group of Knong Riel farmers, Sawathey Pothithey, a member of the Supreme Consultative Council and the founder of minor political party Dharmacracy, visited the area in January 2020 and again in September 2021 to produce a report for then-Prime Minister Hun Sen. She described the destroyed structures as homes that appeared to be part of “a village where people have resided for a long time.”

“When I go there and see people have been abused again and again. As a Cambodian, I cannot stop my tears from dropping down,” Pothithey said.

After her first visit, the Prime Minister’s cabinet ordered the Minister of Environment in November 2020 to review the operations of Wildlife Alliance and the provincial Department of Environment in Knong Riel following reports of alleged abuse.

Many of the Knong Riel farmers had applied for land titles with their village chief in October 2020, but authorities chose not to grant land titles and Pursat’s then-Governor Mao Thonin issued an order in December 2020 to “take action to prevent illegal encroachment on forest land and construction of houses” in the park.

In September 2021, nearly one year after the Prime Minister’s cabinet requested the Environment Ministry review Wildlife Alliance’s activities, provincial authorities and Wildlife Alliance representatives convened in a meeting to discuss the Knong Riel case.

At the meeting, Pursat Department of Environment director Kong Puthira defended the actions of authorities and Wildlife Alliance and said they had only removed huts and tents, according to the Supreme Consultative Council’s report of the discussion, written by Pothithey. She concluded that the Environment Ministry’s description of patrolling tactics and actions in Knong Riel was “not transparent and did not match reality.”

In March last year, several Knong Riel farmers sued sub-national authorities and multiple Wildlife Alliance staff, including Dragos, on behalf of 89 families who had allegedly lost their homes, crops and farming equipment; court documents from the suit were reviewed by CamboJA. (Lefter said he was unaware of a court complaint against the NGO’s rangers).

“We cannot allow them to strangle us, so we need to stand up for ourselves,” said Heng Sophorn, one of the lawsuit’s plaintiffs, who said her home was destroyed in 2020 after farming in Knong Riel since 2013. Her husband, a former Khmer Rouge soldier, has lived in the area since being decommissioned in the late 1990s. Without a home, Sophorn, her husband and their two children sleep under a tarp.

“These individuals were conspiring to destroy the livelihoods of 89 families,” the lawsuit read, containing a range of photographs of crops and homes before and after they were dismantled and, in some cases, burned.

The Department of Environment’s Puthira acknowledged most of the farmers were from nearby Angkrong village and that there was no illegal logging in Knong Riel, merely farmland, which he claimed could cause erosion harming the Pursat river winding around the park’s northern boundaries.

Sophorn said she withdrew the lawsuit after the court promised them they would be left alone — and a court letter noting the lawsuit’s withdrawal, viewed by CamboJA, states local authorities would “negotiate” with the families in Knong Riel over their farming rights. But within weeks of withdrawing the lawsuit, Sophorn’s husband and nephew were summoned to court for questioning on charges of illegal forest clearance. Wildlife Alliance patrols still visit the area almost daily, she said. The Pursat provincial court did not respond to requests for comment.

“Why do they [authorities] still consider it a protected area?” Sophorn said. “I do not think there are natural resources left to be protected besides the farmland of corn and cassava.”

Trouble on the Horizon

While many in the conservation community applaud Wildlife Alliance for its perceived effectiveness in staving off deforestation, others argue that home burnings and the confiscation of farming equipment exacerbate inequalities.

“It’s pushing people into a more precarious position, that will probably end up forcing them to destroy more forests, and to clear land elsewhere. It certainly doesn’t solve the problem,” said one conservation researcher, who requested anonymity as they work with the Environment Ministry. “There’s hundreds of thousands of farmers who need land that has not been available, due to a land market which tends to concentrate lands amongst the wealthy.”

No options for relocations for landless or near landless farmers in Knong Riel appear to have been offered at the time of the evictions. Some farmers had applied for land ownership but were rejected by the provincial administration. Former Phnom Kravanh district governor So Sahong, who oversaw the evictions at Knong Riel, declined to comment, but has described people occupying land inside a national park as “hoodlums” who should be “punished without exception.”

Forest degradation from Cambodian smallholders is often driven by limited access to affordable land ownership, forced displacement and dispossession, and a lack of economic opportunity elsewhere in the country, studies have shown.

The problem is far from unique to Knong Riel: one study estimates that approximately 600,000 to two million hectares of additional land will be needed by 2030 to support the livelihoods of smallholder farmers.

Though Cambodia’s 2001 Land Law provided ownership to anyone who could prove they had occupied land since 1996, the law failed to grant land ownership to many Cambodians and opened up pathways for giving away swaths of land to corporations. In one instance, the government awarded a more than 300,000 hectare concession of forested land to a notorious logging company just 25 kilometers to the east of Knong Riel in the early 2000s. And well-connected elites are still receiving large-scale concessions inside protected areas originally established by Wildlife Alliance.

Some researchers have argued authorities could allocate land ownership in already degraded areas, such as converting old economic land concessions into social land concessions to house poor families. In 2020, Hun Sen also urged ministries to grant land titles to people who have lived inside protected areas for more than 10 years. But instead, since July, the boundaries of Cambodia’s protected areas have vastly expanded by more than one million hectares, overlapping with land already in use by existing communities.

“In case we have to move people out of the [protected] area, for poor families that have no other lands to live on, we should talk and find land that we can provide to them,” said Heng Sopheana, who since 2022 has served as district governor of Phnom Kravanh, which includes Knong Riel.

Existing social land concessions have not yet occurred on a large enough scale to fully address the scope of the land shortage. Plans for land titling in protected areas have not been completed in most provinces, or in some cases spurred the siphoning of land to elites instead of local communities.

Another problem for farmers in or near protected areas is the lack of zoning. Cambodia’s Protected Area Law mandates clearly identifying areas historically used by communities and reclassifying already degraded forest areas. The 400,000 hectare former Central Cardamom Mountain National Park, like many other protected areas representing more than 40% of the country’s land mass, has not completed zoning to identify different forms of land use inside the park. Entire communities appear to still live within the park’s boundaries.

In mid-July, Pursat authorities announced they would offer families using land in protected areas the opportunity to apply for ownership, and Sophorn said she and other Knong Riel farmers were applying but were unsure what would happen.

The treatment of people around the park is also significant given Conservation International’s plans for a carbon credit REDD+ project in the Central Cardamoms region, set to include Angkrong village, whose residents farm at Knong Riel, as a partner community. In November 2022, the Environment Ministry received $15 million from the German and French government-funded Legacy Landscapes Fund (LLF) to manage the former Central Cardamom Mountains National Park, with Conservation International listed as its “partner.”

LLF executive director Stephanie Lang said her organization’s due diligence study prior to issuing funding “did not uncover” allegations of home burning, property destruction and physical violence in the park, though there had been no on-site visit due to Covid-19 restrictions. She said the zoning of the park could “mitigate many of the conflict areas” and Conservation International would develop a “stakeholder plan” to reduce “adverse impacts.”

“Neither LLF nor CI [Conservation International]…have authority over the government’s decisions about which organizations are permitted to operate in the park,” Lang wrote in an emailed statement. “The resources we provide do not and will not support the ranger work undertaken by Wildlife Alliance.”

Conservation International said in an emailed statement that it is now “conducting a review” of activities in the Central Cardamoms, including its donors and “the work of other organizations there.”

Wildlife Alliance’s Lefter countered that Conservation International “seem quite satisfied that we are doing their job” because “we protected their forest.”

Many of the Knong Riel families whose homes were destroyed have continued to farm in the area, alerting each other as soon as Wildlife Alliance-led ranger patrols enter the area.

Knong Riel farmer Sinn and her daughter still sleep on a wood platform with a plastic sheet draped over to guard against the rain and the cold.

“I do not have any place to live and I also did not know what the authorities keep this area for,” Sinn said. “I do not want to live illegally like this. I just hope one day the authorities will give me the land title.”

She slumped to the ground, sobbing.

Then, from down the road, came the sound of revving motorbikes and alarmed shouts as farmers fled. A group of masked men in camouflage uniforms with guns slung over their shoulders ascended the rocky slope.

The rangers were coming.

Two Cambodian freelance journalists contributed reporting to this story but requested anonymity to avoid repercussions.

Editorial Note:

On September 25, the organization Wildlife Alliance published a statement in response to the CamboJA News article “Burning Homes in the Name of Conservation: NGO Wildlife Alliance Cracks Down on the Poor.” Wildlife Alliance stated that it “strongly refutes the unsubstantiated claims and allegations” in this story.

The statement took issue with the article’s description of Knong Real as a “contested stretch of land.” CamboJA stands by this descriptor, as the story outlines various disputes between Wildlife Alliance representatives and villagers related to the villagers living or farming on the land.

Aside from this one example, the statement does not specify what Wildlife Alliance strongly refutes or any other claims it considers unsubstantiated. The organization also accuses CamboJA News of “issuing non-factual stories,” without stipulating what stories or what facts the organization disputes.

CamboJA strongly rejects Wildlife Alliance’s baseless accusation that CamboJA has a “political agenda to denigrate all conservations [sic] efforts done in Cambodia,” a notion frequently lobbed at independent media doing original and investigative reporting in this country.

The Wildlife Alliance statement falsely claims that the article was created without examining the facts on the ground. CamboJA reporters made three on-the-ground visits to the area, including multiple visits to Knong Riel. Satellite imagery of the area, showing deforestation inside the protected area boundaries, is highlighted in the article.

As journalists, we seek out and allow subjects of news coverage to respond to criticism or allegations of wrongdoing. Wildlife Alliance staff members Eduard Lefter and Lida Leng met with CamboJA reporters for a multi-hour interview and their viewpoints were given ample space in the article. Wildlife Alliance CEO Suwanna Gauntlett did not meet or respond directly to CamboJA’s questions. Wildlife Alliance was initially sent an in-depth list of allegations and information to review and comment on in March 2023. The organization was also given detailed descriptions of each allegation of mistreatment from a range of sources, including by name when the source had consented to speak on the record, but Wildlife Alliance only directly addressed one of those cases.

CamboJA takes feedback from sources and readers seriously, and stands by our reporting.

This editorial note was added to this story at 4:15 p.m. ICT on October 4, 2023.