Preah Vihear Province — Sam Sak stands amidst a landscape of cleared earth, surrounded by cassava stems planted like flags to claim their place inside the Kulen Promtep Wildlife Sanctuary.

“This is all protected conservation area,” said Sak, gesturing to the fields upon fields of cassava cleared and planted mostly in the past five years, fringed by receding trees. “Before, it was forest.”

The expanse of cassava reflects the vast, ongoing transformations across mainland Southeast Asia’s forest frontiers. Fueled by an abundance of credit and growing market demands, cash crop booms like cassava pose complex and still unresolved challenges to conservation efforts in Cambodia’s protected areas, while driving deforestation by smallholder farmers who use around 10 hectares of land or less.

As chief of Prey Veng village, Sak had once been a member of the IBIS Rice program, funded by Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The conservation and rural livelihood program arrived in Prey Veng in 2008, promising farmers significantly higher-than-market-rate prices for their rice and other community benefits, so long as they adhered to organic growing techniques and did not clear additional forest.

While 89 of Prey Veng’s approximately 150 families were once IBIS Rice suppliers, last year only six actually contributed organic rice, according to the community’s IBIS representative. More than 75% of Prey Veng farmers have dropped out or been expelled from the program since its peak in 2015.

These farmers, including Sak, abandoned a guaranteed mark-up for selling organic rice to IBIS because they have found there is more money to be made growing cassava. They ditched the time intensive organic rice growing techniques promoted by IBIS Rice to focus on speedy planting aided by herbicides — incompatible with IBIS Rice policies but allowing farmers more time to cultivate cash crops, particularly cassava.

“I cleared farmland for planting cassava in 2017, and they have said that I cleared the forest,” Sak said. “When I started to plant, it broke the conditions of the organization. I have encroached and expanded more of my farmland. Ninety percent of farmers [in Prey Veng village] have expanded their farmlands.”

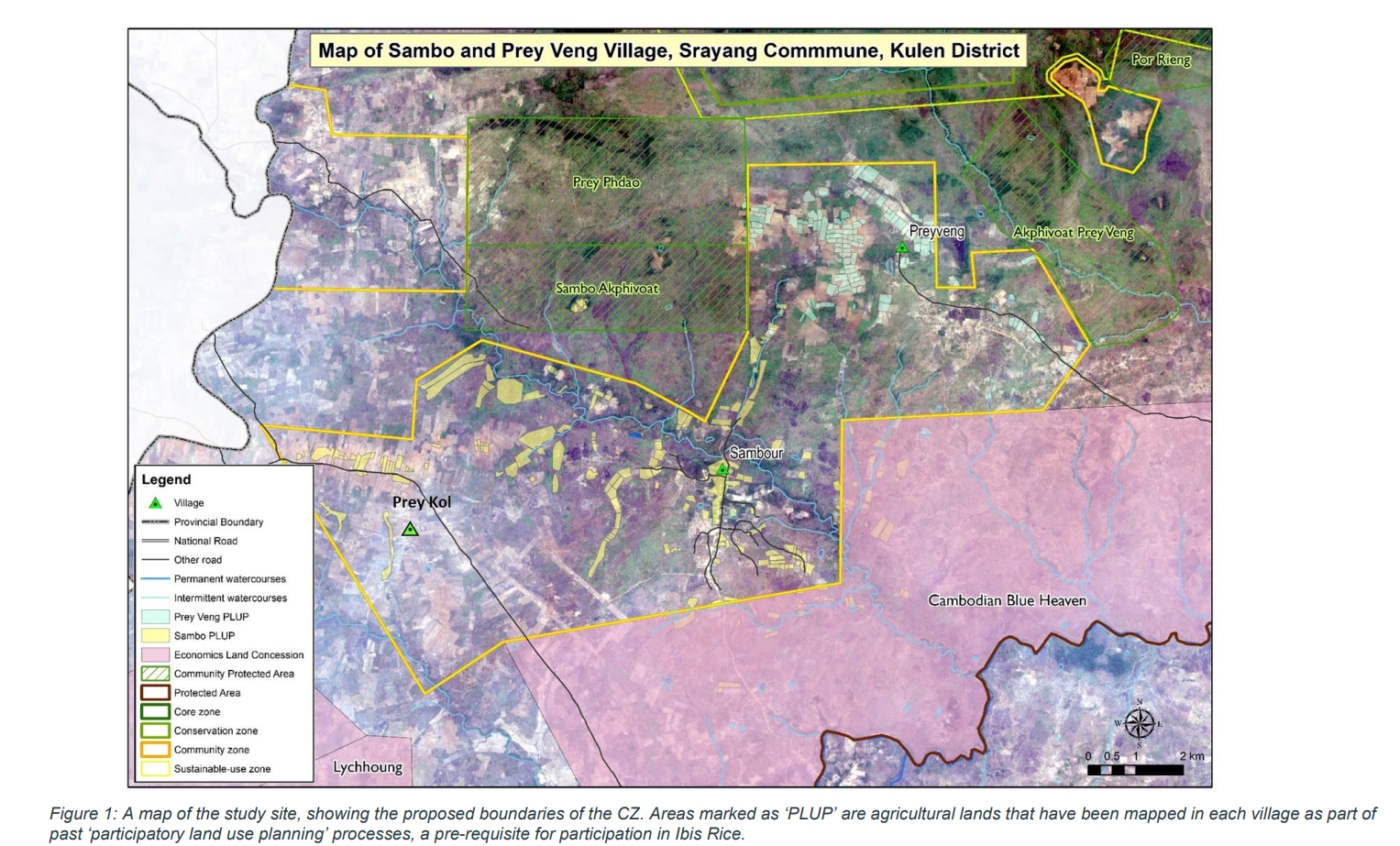

Expanding smallholder farmlands through deforestation is made easier by a rise in microfinance lending available to people in protected areas. Microfinancing is supported by tens of millions of dollars in funding from the U.S. and other western governments, even as they try to promote conservation programs in those same areas. A USAID-funded study released publicly earlier this year unpacked the tangle of microfinance, migration, deforestation, cash crops and the multitude of factors altering land use in Prey Veng and neighboring Sambour village inside Kulen Promtep.

IBIS Rice operates in 49 different villages, many of which have not experienced high drop-out rates from farmers, likely because farmers are more limited by the geography of their lowland rice paddy fields. In Prey Veng and Sambour villages, bountiful fertile highland soil safe from flooding during the rainy season has created a greater opportunity cost to not planting cassava. A pervasive feeling of land insecurity due to widespread land grabbing from outsiders has contributed to high rates of farmer expulsion as IBIS members and their neighbors try to secure additional lands. But the root causes behind the decline of IBIS Rice in the two villages remain indicative of more widespread problems inside protected areas.

“The core issues identified here are playing out all across Cambodia’s protected areas,” said Emiel de Lange, the study’s lead author and a WCS Conservation Impact Technical Advisor since September. “In many areas, agricultural expansion by smallholders is the primary cause of deforestation, and access to credit is a key factor in this expansion when it is provided without consideration of [Cambodia’s] Protected Area law.”

There have been several main causes of deforestation in Cambodia. Large-scale commodity-driven agriculture, notably from the more than 200 state-granted economic land concessions (ELCs) sprawling across two million hectares of land, has led to at least one third of the deforestation in Cambodia over the past twenty years. And organized illegal logging syndicates, often connected to these same concessions, have devastated protected forest areas, operating with relative impunity. Cambodia has lost 155,000 hectares of forest per year since 2011.

But since a moratorium on ELCs was issued in 2012, smallholder farmers are believed to have become an even greater cause of deforestation in the past decade, especially in protected areas across Cambodia. Exacerbated by Cambodia’s underlying lack of land rights for the rural poor, boom and bust cash crops are incentivizing smallholders to clear land, propelled by growing global demands for cassava and abetted by a rise in the accessibility of microfinance credit.

“It’s not just in Cambodia, these sorts of practices are happening around mainland Southeast Asia,” said Sango Mahanty, an Australian National University researcher who focuses on environmental change. “It’s very much part of these broader market processes that are going on.”

The Rise and Fall of IBIS Rice in a Frontier Village

When IBIS Rice arrived in Prey Veng in 2008, villagers were enthusiastic. Situated in a remote area classified as protected forest since 1993, the village had poor road access which meant farmers had been forced to accept cut-throat rice prices from the few traders willing to make the trek. Now, they were being offered double market price for their harvest.

The tradeoff meant accepting the organization’s conservation policies. Building off the villagers’ customary land claims, the Provincial Department of Environment mapped out 8,424 hectares of land as a provisional “community zone” within the protected area. The zone encompassed the two villages and their customary farmlands, solidifying villagers’ existing land claims and prohibiting further development without government permission across more than 6,700 forested hectares, according to de Lange’s study.

Within a year, the IBIS Rice program had grown to more than 80 farmers, over half the village, and participation rates remained high until around 2017, before dropping off sharply in the last two years to only 18 members, according to data IBIS Rice shared with CamboJA. Around that time, cassava was introduced by migrants arriving from Kampong Cham and other land-poor provinces.

Cassava, though tied to the whims of an unstable global market, is an ideal cash crop because it can be easily planted by reusing old stems and the plant’s tubers are ready for harvest within a year, providing an annual return on farmers’ investment, unlike cashews or rubber which are expensive to care for and require years of waiting before profits can be made. Thai and Vietnamese factories process much of Cambodia’s cassava before sending it on to primarily Chinese factories to become starch, MSG, biofuel, ethanol and other additives like sweeteners and syrups. Cambodia is among the world’s top cassava producers and the United Nations has sought to increase the Kingdom’s output.

The crop has become so popular around Prey Veng that even the Ministry of Environment rangers grow cassava outside their station to earn extra money. Stacks of cassava stems awaiting planting can be seen all over the village.

“People are interested in conservation and they care about protection, but they have to help themselves first by having enough to eat and a suitable livelihood,” said Chhorn Chhim, Prey Veng’s IBIS Rice coordinator, admitting most people were now farming cassava in his village.

Farmers earn around $500 per ton of organic rice, compared to around $200 per ton for normal rice and cassava. But while one hectare of organic rice produces about two to three tons of harvest, a hectare of cassava yields upwards of 13 tons, depending on the soil quality.

What these mostly poor, rural farmers choose to invest in planting means a difference of hundreds or even thousands of dollars in a country where the annual income is less than $2,000. Greater profits allow farmers to pay emergency medical bills, fund weddings, keep their kids in school for longer, or build new homes.

Two years ago, 21-year-old Heng Sopha and her husband were expelled from IBIS Rice, for which they had been farming three hectares of rice paddy, because they cut down a half hectare of forest to double the size of their existing chamkar, or highland farm, and plant cassava.

Sopha said they would have cut down more trees but this was the extent of the land they held through the village’s informal customary system, established when people returned to the area following the collapse of the Khmer Rouge in the late 1990s.

Traditionally, Cambodian farmers like Sopha engaged in the labor intensive practice of transplanting rice, which requires letting rice seedlings grow for several months before planting them by hand across rows of clear paddy to get a head start over weeds. To transplant a hectare of paddy can take a single person an entire month.

But with the lure of cassava, many Prey Veng farmers shifted to the much easier method of broadcasting — scattering rice seedlings throughout a paddy and then letting them grow naturally without replanting later. Transplanting kept farmers tethered to their fields for months, whereas broadcasting farmers could finish the task in only a few days.

In spite of the hard labor involved, transplanting had historically been the preferred approach for farmers because it was the most efficient use of valuable seeds, while broadcasting left rice seedlings much more vulnerable to weeds without chemical protection. That changed for Prey Veng farmers with the gradual availability of herbicides and the influx of credit needed to buy them.

Inspired by their neighbors, Sopha and her husband took out a $1,000 microfinance loan from AMK last year to purchase cassava stems, fertilizer and herbicides to aid their farming. The new cassava field required their time and the loan supporting it meant they needed to find additional work to pay back the monthly interest payments.

“The rest of time after broadcasting seeding, we can labor somebody’s farmland as seasonal cultivating cash crops, or transplanting for other farmlands,” said Sopha.

“I am not interested in returning to the organization’s program [IBIS Rice],” she added. “Because we will not receive much yield [from transplanting] and we don’t have time to clear grasses; if we don’t use chemicals [pesticide and herbicide], insects will eat our rice paddy and not receive yield.”

The same changes had begun several years before in Sambour village, located closer to the regional capital, and farmers across both villages repeatedly echoed the same reasons for favoring cassava and broadcasting rather than the organic transplanting pushed by IBIS Rice.

Sambour villagers Chan Lorm and her husband were expelled from the IBIS Rice five years ago after illegally expanding the head of their rice paddy by 40 meters into the forest to support their growing family. In the community’s traditions of land management, families were allowed to expand the head of their farmland when needed. Lorm’s son and his wife, lacking land to farm, have currently set up a grocery shop on the street corner by Lorm’s home.

Lorm has since borrowed $500 from a microfinance institution to establish her cassava crops across two hectares and also to purchase pesticides and herbicides for three hectares of rice paddy once reserved for IBIS Rice.

“We have expanded the farmland because our land is small,” Lorm said. “Rice wasn’t a good yield because there were a lot of [weeds].”

Socheat Keo, the director of IBIS Rice’s local NGO partner Sansom Mlup Prey (SMP), acknowledged that people in communities like Prey Veng could no longer be expected to transplant rice with their bare hands.

“Human labor is not the future,” Keo said. “We cannot depend on people to transplant the rice anymore, it is time consuming and labor intensive.”

He said SMP and IBIS Rice were trying to help Prey Veng and other communities get access to machines to save their time. They were planning to introduce a “direct seeding machine” connected to a hand tractor to plant seeds and a transplanting machine to put seedlings into tidy rows. But these machines are costly, as much as $6,000 for a slick motorized transplanting machine, though a manual version can be had for only $200. Keo feared it would be difficult to fix the machines or find replacement parts if they broke.

“It is slow in the remote area, people are not skilled and to change their behavior takes time,” he said, noting that nobody in either Prey Veng or Sambour is currently using any of the machines.

Deforestation and the Role of Microfinance

While organic rice farming appears to be unable to meet the economic aspirations of many farmers in Prey Veng and Sambour, it is also apparent that the prevalence of microfinance lending in both villages drives deforestation and incentivizes a shift away from organic farming, noted SMP’s Keo.

Increasing reliance on credit is part of a decades-long process of agrarian change happening all over Cambodia and around the world, as subsistence farming limited by a family’s access to available labor from their children and relatives gives way to cash crop-driven planting limited instead by a family’s credit access, de Lange said.

But everyone involved in the IBIS Rice program said reforms are needed to minimize the MFI industry’s role in supporting illegal clearing. ACLEDA, AMK, Sathapana, Woori Bank and Prasac all lend in the area, according to Prey Veng and Sambour farmers.

MFIs willingly accept soft land titles inside protected areas as collateral for loans even those these practices are generally illegal, de Lange found in his study, which Keo, villagers, and village leaders also confirmed to CamboJA.

Despite widespread calls for industry reform, there is underlying dissonance as donors funding conservation efforts inject cash into the MFI industry. The U.S. government, which has provided direct support to the IBIS Rice program, has also poured millions into a range of microfinance institutions, such as a $125 million direct loan to ACLEDA in 2016 and $15 million to AMK and two other MFI institutions in 2017.

U.S. Embassy spokesperson Stephanie Arzate said USAID is focused on “conserving forests” and that no new assistance had been provided to MFIs since last year, following a series of reports on the industry’s negative impacts on human rights. While Arzate did not name the specific reports, the German government released a study last year showing the industry had led to significant overindebtedness, the first critical report from a major MFI donor.

WCS urged for greater regulation of the MFI industry in an emailed statement to CamboJA. “MFI loan due diligence and compliance with protected area laws pose significant challenges” to the IBIS rice program, WCS said, noting that some MFIs “prioritize financial and growth objectives over sustainability or conservation goals.” WCS added that some MFIs’ practices can “inadvertently promote deforestation, land clearing, and pesticide use in protected areas.”

“MFIs play a crucial role in rural development and the transitioning agricultural sector, making it vital to prioritize the regulation of MFI loan compliance and due diligence within protected areas,” WCS added.

Two MFIs lending to Prey Veng and Sambour farmers, AMK and ACLEDA, categorically denied involvement in funding forest clearance or any other illegal activities, in responses to CamboJA. The rest of the MFIs identified as lending in the two villages did not respond to requests for comment.

Cambodia Microfinance Association (CMA) spokesperson Tongngy Kaing said in an emailed statement that CMA would review the USAID study and that CMA remains “committed to eliminate any potential harms that may be caus[ed] by financial service in Cambodia.” WCS had not reached out to CMA, he said.

“Loans to illegal activities are prohibited by the laws,” Kaing said. “It does not make any business sense for any bank or MFI to lend for deforestation or illegal activities as it will result in both financial and reputational risk.”

“We have provided loans for [borrowers] to expand their businesses, it isn’t involved with the forest,” ACLEDA CEO In Channy said. “Our loans provide for increasing their products and businesses.”

But for farmers in protected areas to “expand” their business, they must often illegally clear land, said SMP’s Keo, a sentiment confirmed by villagers from both Prey Veng and Sambour. MFIs should thoroughly review farmers’ business plans and have a responsibility to monitor how they used their loans, Keo argued.

“What we can see in reality, people get a loan and invest in agriculture in the protected area,” Keo said. “To invest in agriculture in protected areas is often to invest in deforestation. To get the land for farming is to clear the land.”

The Migrant Labor Growing Cash Crops

The cassava boom around Prey Veng and Sambour villages is influenced by a steady flow of migrants moving into the area, who offer cheap labor to help local farmers plant and harvest their expanding farmlands. Microfinance loans often support the wages for these migrants and seasonal laborers.

The migration into the area is part of a larger trend across Cambodia, as hundreds of thousands of the rural poor strive to secure cheap and available farmland in forest frontiers. While many Cambodians have flocked to Phnom Penh and other cities to take jobs in construction and garment factories, the majority of migration in Cambodia has actually been between rural areas, including by families pushed from their original homes by land grabs or microfinance debt.

Lon Mech, 52, and his family of seven are among Kulen Promtep wildlife sanctuary’s new arrivals. On one afternoon in March, they rested on a few planks of wood platform, with two plastic tarps lashed over to provide protection from the sun. The 20 by 60 meter strip of dirt they had purchased from a Prey Veng villager for $700 was all they owned. Mech said he had learned land was available while working transporting dead trees from inside the protected area.

The family had migrated from Siem Reap province in December, among the migrant families living in an area of Prey Veng village called “plastic town” due to residents’ cheap plastic shelters. Mech’s family earned 150,000 riel or around $37 for every ton of cassava they harvested, which took about a week per person.

Mech said his family had lost the last of their lands after taking out a microfinance loan to build a house that was never finished back in Siem Reap. He now dreamed of buying his own plot to farm, though he was still paying off his $3,000 Prasac loan.

“A lot of land belongs to local villagers, in case they need to sell at a cheap price, if we have money we can afford to buy it,” Mech said. “Land here is still cheap.”

But his neighbor, a 25 year old woman named Ton Im, moved to plastic town with her husband to farm one hectare of land they had received from his family. It isn’t enough to survive on, and they hope to secure more land while continuing to work as laborers for others. “It’s hard to get land if you have no money to buy it,” she said.

Cassava isn’t only fueling migrants to existing villages, it is also leading to the formation of entirely new communities inside protected areas like Kulen Promtep. Down the road from Prey Veng, around 155 families have cleared away hundreds of hectares of forest in the past decade, mostly to farm cassava, in a sub-village of Sambour called Prey Kol, within the community zone originally created through IBIS Rice, de Lange’s study found.

While some of the land originally belonged to local farmers, much of the previously forested area had since been sold to landless migrants from all over the country who had descended there. Many local farmers felt pressure to claim fertile lands as more migrants, some of them allegedly tied to wealthy brokers according to de Lange’s study, flooded the area.

“I don’t have farmland and I heard that there was a lot of land here, I came to find farmland,” said An Sea, 54, who grows cassava on several hectares he bought from a Sambour native 10 years ago.

Although most of the Prey Kol farms were initially illegally cleared, the area was later given formal recognition as a sub-village of Sambour by authorities.

SMP’s Keo argued that it was important to improve access of poor and landless families to farmland and offer pathways to legal ownership, as long as precautions were made to ensure the families’ didn’t simply sell off their lands to the highest bidders.

“We wish to see landless people get the land and we support those people, they can remain,” SMP’s Keo said.

Environment Ministry spokesperson Neth Pheaktra said there are around 200 recognized communities in protected areas and that the ministry was still working on registering and zoning land in protected areas. Regarding organic rice farming, he said there has been “successful implementation” with communities in Preah Vihear’s protected areas and the law would be enforced on any additional land claims.

Searching for Solutions

There is no “silver bullet” answer to solving the multitude of issues underlying the cassava boom and agrarian changes sweeping through Kulen Promtep, and the high program drop-out rates of farmers in Prey Veng and Sambour villages should be considered more extreme examples, says IBIS Rice CEO Nick Spencer.

“We’re definitely not walking away from these communities,” Spencer said. “But I think the changes — we could have understood them better earlier.”

“We deliberately go and work in the places where it is going to be hardest for us to succeed,” he added. “We want to react to reality, we want to have solutions that are durable to these changing systems. In some places we can’t catch up and in other places we really see positive change through our consistent approach.”

In the past few years, IBIS Rice has expanded to villages in three other provinces: Stung Treng’s Prey Lang and Siem Pang forests, Mondulkiri’s Keo Seima wildlife sanctuary and Ratanakiri, where many villages have expanded participation or avoid large drop-out rates, according to company data shared with CamboJA. The results have been more mixed in Preah Vihear villages participating since 2016, with about five of 12 villages declining significantly in participation.

Spencer emphasized the high expulsion rates in Prey Veng and some other villages meant the program’s monitoring to ensure organic standards were working properly.

“We don’t want to start working with land that’s been recently deforested,” Spencer said. “You know, that would not be what our consumers expect. And you can’t keep shifting the baseline.”

The program could try to maximize the profitability of existing legal farmland people had by allowing other popular crops into IBIS Rice, such as galangal, palm sugar, sesame, chiles, ginger, cashews and even cassava, Spencer said.

“My hope is that we can get variety in production for an IBIS Rice curry paste,” Spencer said. “I think the resilience is in diversification.”

IBIS Rice is also improving infrastructure by digging out ponds to provide farmers with water access during drought and developing crop insurance to reduce reliance on debt and financial collapse in the event of crop failures due to bad weather, Spencer said. He hoped his company’s expanding market access in Europe and other global markets could lead to higher prices for farmers and keep the program attractive.

Still, “if it’s a comparison between IBIS Rice and unlimited deforestation and cassava production, we cannot compete,” Spencer said. “I don’t think that’s the outcome anybody wants and I don’t think that’s the benchmark we should set ourselves against.”

But for farmers inside Kulen Promtep wildlife sanctuary, a tradeoff between deforestation and cassava or organic rice for lower profits and harder work seems to many like their only current choice, even as the forest grows scarcer and an inevitable cassava bust looms in the years ahead, along with increasingly depleted soil maxed out by fertilizers and poisoned by chemicals.

One cassava trader, Seu Rakmey, said that he had recently purchased 600 tons or 20 times the yield of IBIS organic rice that year from Prey Veng village. He sipped tea in his office at nearby Prey Kol, in the middle of protected land cleared of forest in every direction, waiting for more cassava farmers to come with their harvests which he would transport to buyers in Vietnam. For the moment, he said, demand appeared limitless.

“All the cassava that farmers want to sell, I will buy.”