Cambodia’s protected areas have expanded by more than 550,000 hectares across 12 provinces, government sub-decrees issued on July 17 reveal.

Conservationists and environmental activists warn that the vast transformations will likely trigger land conflicts due to a lack of consultation with communities living in or around the new boundaries under the control of the Environment Ministry.

They also questioned authorities’ willingness and ability to protect the newly classified land, given high rates of deforestation and land concessions to elites inside existing protected areas.

“The important thing is whether there are forests in the area to protect or not? Sometimes, there is no forest to protect,” said Heng Sros, an activist with the Cambodian Human Rights Task Force. “The size of wildlife sanctuaries has increased but what worries us is that the authorities…do not seem to prevent [deforestation].”

Lumphat, Phnom Nam Lea, Phnom Prich, Keo Seima, Kulen Promtep wildlife sanctuaries and Bokor and Veun Sai-Siem Pang national parks all expanded their boundaries, in some cases by tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of hectares.

The Central and Southern Cardamom Mountains national parks merged, along with reclassifying more than 114,000 hectares of adjacent biodiversity corridor, to become the 926,123 hectare Cardamom National Park.

Prior to the expansions in July, protected areas already covered more than 40% of Cambodia’s land mass and due to a lack of zoning typically have communities still living within them. Only two protected areas, Botum Sakor National Park and Sre Pok Wildlife Sanctuary, decreased their size, based on existing sub-decrees. Botum Sakor, much of which had already been distributed to tycoons, had 27,355 hectares cut. Sre Pok only had 264 hectares removed.

Government officials claimed to CamboJA that there will be no issues with converting hundreds of thousands of hectares of land into protected areas, claiming that communities will not be affected.

But reviews of satellite imagery show that farms and economic and social land concessions all appear within some of the newly expanded protected area boundaries.

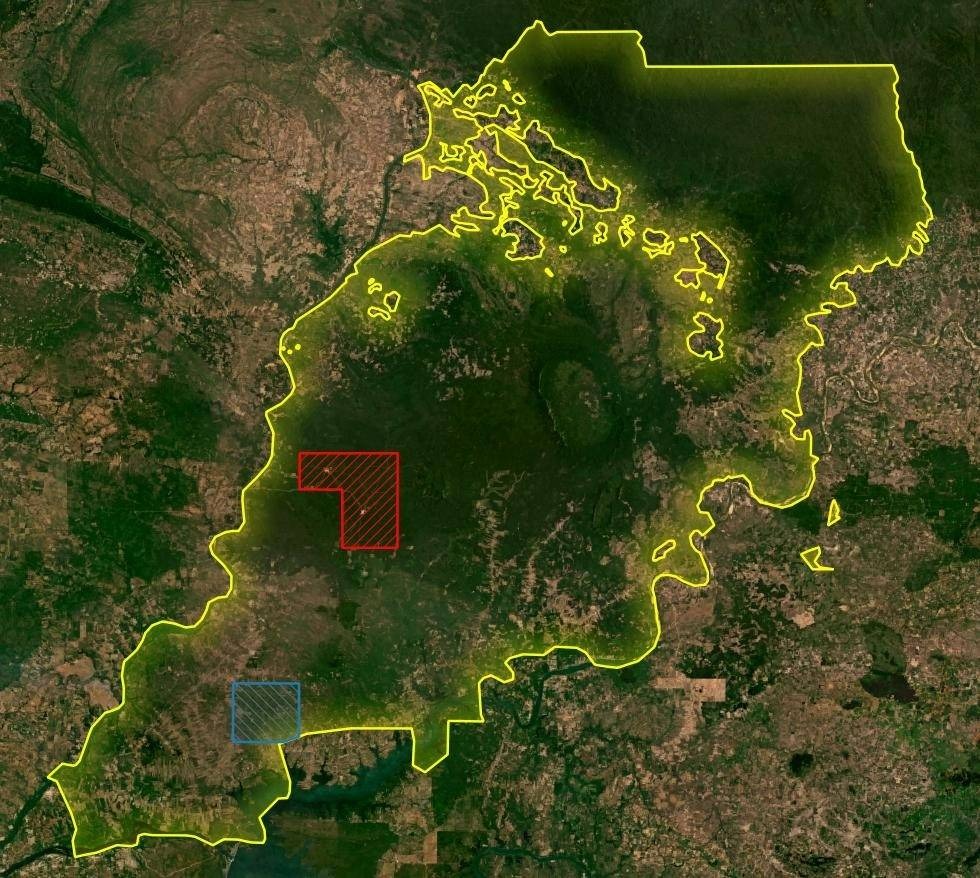

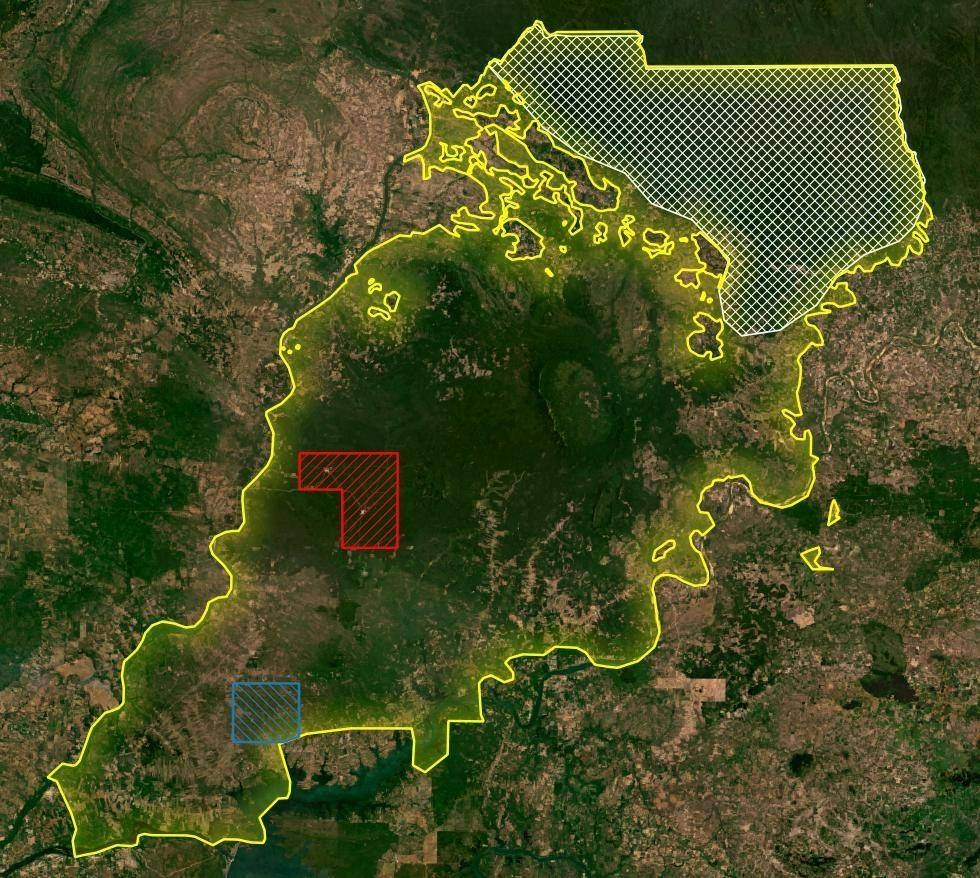

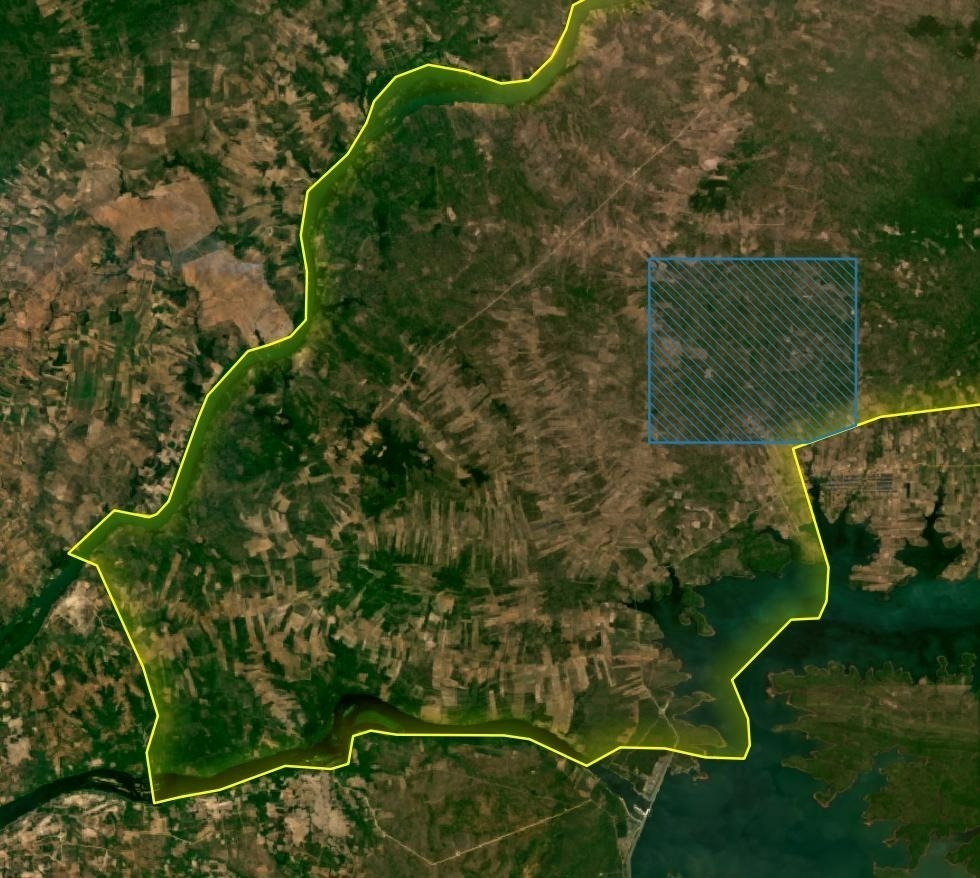

In one case, Veun Sai-Siem Pang National Park’s boundaries expanded from 57,469 hectares to 280,359 hectares across Ratanakiri and Stung Treng provinces. The new protected area boundaries encompass more than 5,000 hectares of land that the Agriculture Ministry had awarded as an economic land concession last year, now being used for large-scale logging operations.

The national park’s extended boundaries also include an area earmarked for a social land concession to distribute to poor families for farming.

Sek Sothea, a coordinator for the O’Svay commune ecotourism center in Stung Treng, said he was not aware that the boundaries of the Veun Sai-Siem Pang national park appeared to now engulf his community’s farmlands, according to satellite imagery.

“We support the conservation areas, but the government has to thoroughly study what the impact is on villagers because in those areas villagers have their farmlands, including the community forest,” Sothea said.

Previously, much of the land reclassified as a national park in Veun Sai-Siem Pang had been designated as a biodiversity corridor, established in 2017, which is a separate land classification intended to connect protected areas.

While biodiversity corridors technically prohibited land ownership, in reality, many communities appear to have had pre-existing land use claims within them.

Agriculture Ministry spokesperson Im Rachana declined to comment and referred questions to the Environment Ministry.

Environment Minister Say Sam Al referred questions to spokesperson Neth Pheaktra, who said the rezoning of protected area boundaries was intended to “strengthen conservation in our protected areas and prepare to register state land.”

“We will demarcate a post where protected areas [expanded] to ensure the awareness of the community,” Pheaktra said. “There is no impact on communities.”

He hung up the phone when asked about the overlap of new protected area boundaries with existing social land concessions.

Phleuk Phearum, a coordinator for Mondulkiri’s Indigenous Provincial Network, said authorities had not consulted with indigenous communities about the expansions of four protected areas throughout her province.

“I am not optimistic about the ‘protection’ of the environmental authorities, because I see that wherever they have been, the place will be destroyed,” she said. “When the environmental authorities come in [to protect the area], my concern is that all the land will be given to a company.”

Only a small number of indigenous communal land titles have been granted, while authorities have also stymied communities’ requests to gain ownership over their land and instead allocated the land for other purposes.

Tim Frewer, lecturer at the School of Field Studies in Siem Reap, said that the process of reclassifying land into protected areas should be done “with the full participation of indigenous people who have been protecting these areas for generations.”

“There are still overlapping boundaries between protected areas, the land of small farmers and areas that have been requested to be registered as indigenous communal lands,” Frewer said. “Indigenous communities, civil society and donors have invested a huge amount in the indigenous communal land registration process.”

Communal land titles provided recognition of indigenous land rights to sacred forests, swidden agriculture plots and forest lands reserved for future generations. But a lack of clear land zoning and titling, both for indigenous and non-indigenous communities living and farming inside protected areas, has long been a source of conflict.

“It is also important to provide titles for poor non-indigenous smallholder farmers who use already cleared land in these biodiversity corridors for basic livelihood activities,” Frewer said.

The government had announced last year that it planned to open up nearly one million hectares of protected area to land titling and rezoning, sparking concerns about land giveaways but also cautious optimism as a way to resolve land disputes in and around protected areas.

Ven Vorn, a spokesperson for the indigenous Chorng minority community, living inside and around the revamped Cardamom Mountain National park, said that boundaries remained unclear between community farmlands and an existing Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Developing Countries (REDD+) carbon credit project.

“They have not mapped the boundary between the use of farmland and conservation land, so we don’t know the impact yet,” Vorn said. “But locals have no right to collect forest products in protected areas.” This appears to have led communities to be banned from farming.

Representatives from the NGO Wildlife Alliance declined to comment on how changes to the protected areas would affect their Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project, recently suspended due to an ongoing investigation by accrediting body Verra following allegations of human rights abuses.

Environment Ministry Undersecretary of State Paris Choup told CamboJA the new protected area rezoning “does not impact [REDD+ projects], which are still continuing normally.”

He declined to comment further.

Expanding in Size:

Lumphat Wildlife Sanctuary has expanded from 250,000 to 356,087 hectares = 106,087 hectares

Phnom Nam Lea Wildlife Sanctuary has increased form 47,500 to 64,835 hectares = 17,335 hectares

Phnom Prich Wildlife Sanctuary has increased from 222,500 to 262,642 hectares = 40,142 hectares

Keo Seima Wildlife Sanctuary has increased from 292,690 to 317,456 hectares = 24,766 hectares

Kulen Prum Tep Wildlife Sanctuary has increased from 402,500 to 428,971 hectares = 26,471 hectares

Bokor National Park has increased from 154,458 to 156,116 hectares = 1,658 hectares

Veun Sai-Siem Pang National Park has increased from 57,469 to 280,359 hectares = 222,890 hectares

Central Cardamom Mountain National Park (previously 401,313 hectares) combines with South Cardamom Mountain National Park (previously 410,392 hectares), along with reclassifying an additional 114,418 hectares from an adjacent biodiversity corridor as protected area = 114,418 hectares of new protected area.

Total increase of new protected areas = 553,767 hectares

Decreasing in Size:

Botum Sakor National Park reduced from 171,250 to 143,895 hectares = 27,355 hectares

Sre Pok Wildlife Sanctuary has reduced size from 372,971 to 372,707 hectares = 264 hectares

Total decrease in protected area size = 27,619 hectares

Impacted Provinces:

Ratanakiri, Mondulkiri, Stung Treng, Kratie, Kampot, Preah Sihanouk, Pursat, Kampong Speu, Koh Kong, Preah Vihear, Siem Reap and Oddar Meanchey provinces.