Roya commune, Mondulkiri province – Indigenous Bunong people from Roya Leu village offered rice wine and pork to a shrine, asking forest spirits to protect their land from the World Bank.

In a clearing surrounded by dense canopy, the community members had gathered in mid-July amidst Roya Leu’s ancestral forests and burial grounds, which the World Bank planned to rezone and redistribute to landless families.

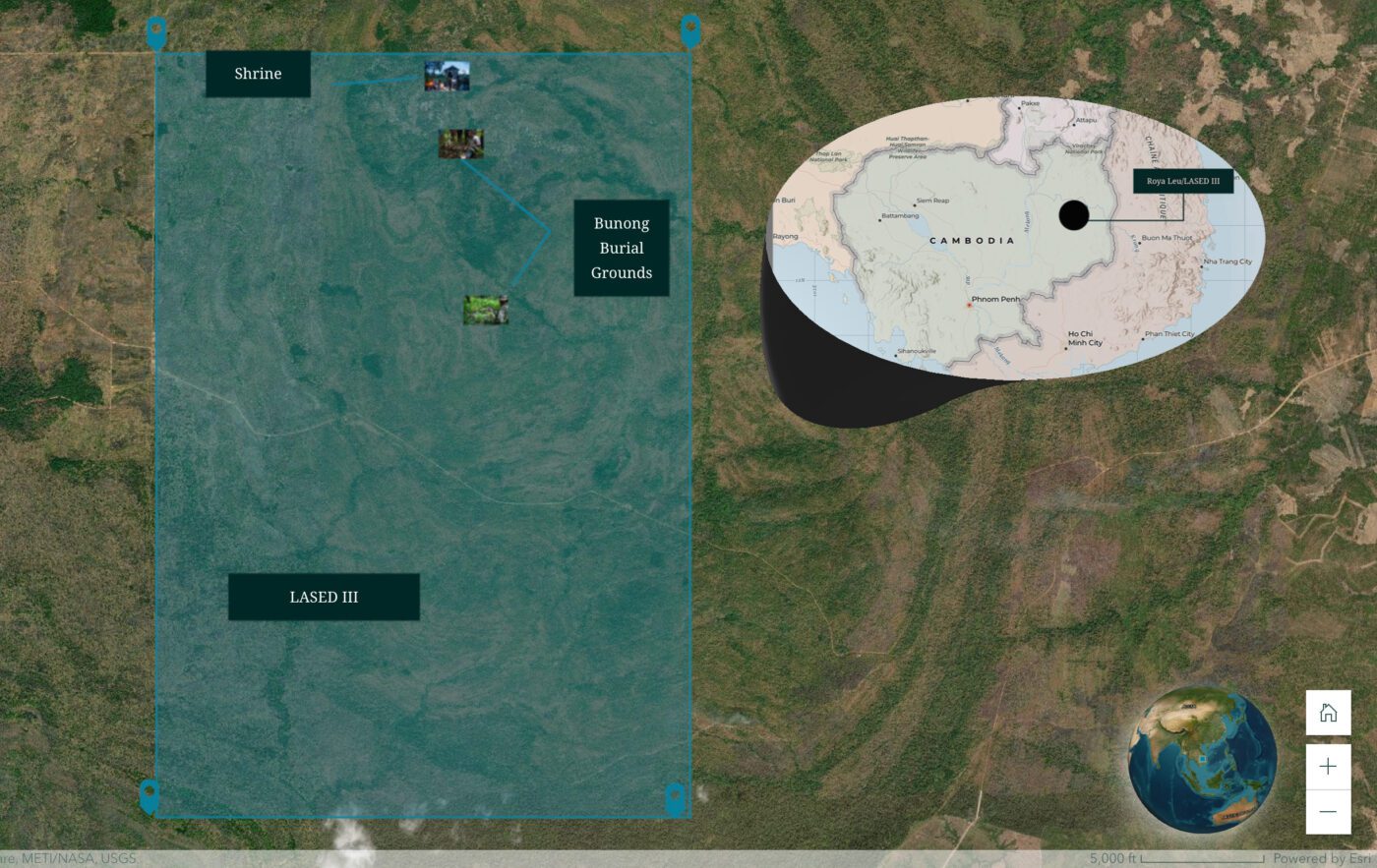

The Land Management Ministry awarded the World Bank a 6,000 hectare Social Land Concession in 2021 encompassing Roya and Soksan communes in Mondulkiri as part of the Land Allocation for Social and Economic Development III (LASED III) project, an initiative intended to increase legal land ownership.

But this concession consumes 3,000 hectares or about 60% percent of Roya Leu’s ancestral forests. While the village of around 100 Bunong families has made requests for legal recognition and ownership of their forests, the World Bank’s project is moving forward, in apparent contradiction to its policies safeguarding indigenous rights.

“Our connection to the spirits and the forests is what sustains our wellness as a community, as well as our sense of friendship and solidarity to one another,” said Lin Moa, a Roya Leu resident. “The forests around us are a part of the health of our community. We lose that sense of well being as the forest disappears and we are impeded from keeping in touch with the spirits.”

As the Bunong people prepared a ritual feast on July 14, LASED III consultant King Vireaksith arrived at the forest clearing with an entourage of public relations assistants and district police officers armed with AK-47s. Vireaksith, who declined to speak with CamboJA, is LASED III’s senior national environmental risk management consultant.

Vireaksith and Bunong community leaders began drawing the boundaries of the World Bank’s concession in the mud, while villagers pulled out smart phones to document the proceedings. The discussions made clear: the Bunong burial grounds were deep within the concession.

More than two years after the land was allocated to the World Bank, this was the first time the Bunong community had the opportunity to speak directly with LASED III project representatives, more than 10 Roya Leu villagers told CamboJA.

Signs declaring the boundaries of the LASED III project had been erected around the forest in March last year, but no explanation had ever been provided, these villagers said.

“We had never heard about it [LASED III] when it was established in the area. Even the village and commune chief never told us,” said Lin Lan, a Bunong Roya Leu resident.

Pil Deth, chief of Roya commune which includes Roya Leu village, denies this and said he told the community when the project was first launched.

Lan explained the Land Management Ministry first broached the topic at a staged declaration ceremony in Roya Leu on June 28, 2023, but the community was not directly consulted or approached by implementation officials. At the gathering, presided over by ministry and World Bank representatives, ministry officials declared that LASED III was going to start the rezoning phase. The LASED III project posted on Facebook that 650 locals from across the two communes in the concession attended.

But Lan and a few other community members said commune authorities told certain outspoken villagers, including Lan, they were not allowed to attend.

Villagers expressed concern to CamboJA that the project will undermine their long-standing land rights claims and their attempt to obtain a Community Land Title (CLT), while threatening their unique cultural beliefs and traditions. Besides their cultural and spiritual practices, indigenous peoples also depend on the forests for their livelihoods and sustenance.

Indigenous activists, human rights groups and Roya Leu community members say the World Bank did not thoroughly consider the social and environmental impacts of its plans to seize Bunong lands through the $93 million LASED III project.

“People in Roya maintain a close connection with the traditional forested lands on which their livelihoods and cultural practices depend,” said Bi Vanny, coordinator for Mundulkiri with the Cambodian human rights group Adhoc. “Land grabs and concessions not only threaten biodiversity and climate, but also significantly undermine indigenous peoples’ culture and human rights.”

The Struggle for Indigenous Land Rights

The Roya Leu community say they have been slogging through the registration process to obtain a CLT since 2016, with no clear end in sight.

A CLT allows an indigenous group to become the legally recognized owner of ancestral forest land. The process spans three ministries and involves gaining approval from village authorities all the way up to the national level.

Since the CLT framework was outlined in 2009, only 40 CLTs have been granted across Cambodia’s 753 indigenous villages. A UN policy review found that the various government agencies involved do not sufficiently coordinate and recommended the process be simplified.

The process got even more difficult earlier this year when the National Assembly removed the terms “indigenous and ethnic minority communities” from key codes managing environmental resources, undermining the preferential weight previously given, in theory, to indigenous land claims.

Roya Leu attained legal recognition and self-identity declaration as a “collective community” at the commune level in 2021 with endorsements from the village and commune chiefs. But the documents are currently stuck in limbo at the provincial level, according to commune chief Deth.

“All documents were signed and thumb printed in the wake of their requests, but when they put them forward to the provincial [rural development department], they were not acknowledged,” said Deth.

Nuon Monichenda, the head of the ethnic minority development department within the Rural Development Ministry, said the CLT had not yet been approved because all relevant documents needed to first be signed by the village chief.

But Chan Moeun, a village chief that has jurisdiction over Roya Leu, told CamboJA he had completed the proper documents for the process. CamboJA obtained a document from 2021 signed by Moeun recognizing the Bunong community.

Monichenda also claimed the group attempted to bypass approval at the provincial level, which was “unacceptable.”

“The Royal Government of Cambodia does not leave IPs [indigenous people] behind,” Monichenda said repeatedly to CamboJA over Telegram.

One Roya Leu villager told CamboJA that Monichenda called her and told her to advise the community not to speak to journalists or NGOs regarding Roya Leu’s CLT process.

Monichenda told CamboJA she would share inquiries about the CLT with the head of the provincial rural development department. Later, though, she deleted all Telegram messages to CamboJA, requested future questions be directed to the ministry spokesperson and stopped responding. CamboJA was unable to reach a spokesperson despite multiple calls to the ministry’s headquarters in Phnom Penh.

The head of Mondulkiri’s rural development department, Yun Sarourm, told CamboJA the community did not follow the proper procedures for the CLT process. When asked how they failed at following the guidelines, Sarourm, whose ministry is involved in signing off on the CLT, said, “Why ask me?”

Meanwhile, the World Bank conducted consultations in April 2020 with the Royal Government of Cambodia, done virtually due to pandemic restrictions, before receiving their concession in 2021. A summary document states that the CLT process and “impacts on indigenous peoples” were a focus of these consultations.

World Bank performance standards stipulate that its projects must “anticipate and avoid adverse” impacts” on indigenous peoples, and if that is not possible, “minimize or compensate for such impacts.” Indigenous community representatives must be included and given sufficient decision making time, the World Bank notes.

Despite the community’s ongoing CLT efforts, by 2021 the ministry publicly predicted that individual land titles would be granted to 15,000 landless families by the project’s completion.

The NGO Cambodia Indigenous Peoples Organization (CIPO) worked with the community this year to write a letter to the Land Management Ministry. The letter, sent on April 4, asked the ministry to postpone the LASED III’s demarcation of individual land titles and respect the community’s pre-existing efforts to obtain an CLT.

The ministry rejected the community’s request, a document obtained by CamboJA shows, stating that the community had not yet been recognized by the provincial rural development department. CIPO Executive Director Yun Mane hopes the ministry will reconsider its decision to grant individual titles.

Roth Hok, Under Secretary of State for the Land Management Ministry and the project director, told CamboJA that the ministry had consulted with all relevant parties, including indigenous people, to collect information on the concession’s potential impact. However, he emphasized the need for further assessment before the LASED III is implemented.

“Until now, we cannot determine how much it [LASED III] is going to affect the people, we cannot say that it will or will not impact indigenous people because it is in the appraisal process,” Hok said.

Reached by phone, LASED III Provincial Social Risk Management Consultant Cheth Kimngoy told CamboJA that his team went to the site in July to understand the situation and have face-to-face talks with the Bunong villagers in order to assess how the project will impact indigenous livelihoods. They are still deliberating on how to address the indigenous peoples’ concerns.

“All relevant ministries are in charge of assessing the impact to people,” stated Kimngoy when asked about how their concession was granted in spite of the Bunong efforts to obtain a CLT. “If the project’s land overlaps with the community’s land, it is important for them [ministries] to make impact assessments and solve the problems or forward them to higher authorities.”

A spokesperson for the World Bank told CamboJA via email that the LASED III project also supports communal land titling for 15 indigenous communities but did identify Roya Leu as one of the villages receiving support.

“The project implementation team has posted signs in Mondulkiri province to communicate dates associated with project implementation,” the World Bank stated.

While the World Bank determines if the LASED III development plan will be adjusted, the Bunong people still do not have any legal ownership or safeguards to protect their forests.

About a dozen people from Roya Leu who spoke with CamboJA consider the World Bank’s concession a direct impact in itself, especially since the World Bank and government officials began surveying for redistributing individual titles without addressing the community.

Community members voiced to CamboJA that they only want ownership of their original homeland, repeatedly emphasizing they are not looking to expand but only protect their land. They are also concerned officials outside the community are illegally claiming and selling land.

Four community members showed CamboJA wooden posts smeared with red paint that they feared village chief Moen and other officials marked to delineate land for sale or deforestation. Just outside the northeast corner of the World Bank’s concession, two soccer stadium sized swaths of forest were cleared this May.

“Do you believe those people? They say what they want to say,” Moeun exclaimed angrily when told about the villagers fears, claiming he is not involved in brokering illegal land sales or land grabbing. He went on to accuse the indigenous people of slandering him.

“I do not engage in these activities,” he said before hanging up the phone.

“If people who cut down forests are environmental officials, or even village and commune chiefs, they are OK,” Roya resident Houm Kluy told CamboJA, meaning they were immune from any prosecution. “They are working as a syndicate, that is why it is onerous for us to obtain a legal, collective community title.”

Environment Ministry spokesperson Neth Pheaktra did not respond to requests for comment.

Burial Sites in the Midst of a Concession

Burial sites for the villages in the Roya commune are deep inside the World Bank’s concession, based on coordinates mapped by CamboJA. The woods around these two burial sites are for rituals and ancestral spirits, said Roya community representative Pla Nen, who guided World Bank and government representatives to these sites when they came in July.

“Traditional burials have been particularly significant for Bunong people for many years and provide important physical and spiritual connections with the land, culture and their past,” Nen said. “The places where the dead are laid to rest have always been important to this community.”

Nen crouched on one knee as he pointed to a piece of a bowl used as an offering jar for an ancestor’s spirit. The deceased were interred here either individually or in small groups, according to Bunong villagers, usually buried with possessions such as stone tools or personal ornaments around the grave.

“We are concerned that there is nothing we can do if local officials allow businesspeople to purchase cemeteries or spirit forests,” Nen said. “If the site is handed to them [the Lased III project development], other traditions will be more abruptly eradicated from this community due to the already rampant land grabbing and deforestation that exist here.”

Roya Leu resident Moa said that these sites involve elaborate funeral rituals, which the Bunong people have been practicing for centuries. One burial site is centered around a circle of rocks used for such rituals and has been there as long as the community can remember, explained Nen. These funerary rites include feasting, animal sacrifice, funeral processions, coffin-making and grave decorating.

“The threat of land seizures and land sales to outsiders has put burial rites, one of the last remaining examples of Bunong custom practiced in this area, in danger of disappearing,” Moa said.

About a dozen other Bunong community members guiding the entourage on this day echoed Moa’s concerns. These cemeteries have been used by Bunong people for thousands of years according to the community.

“Burial grounds also provide us with crucial reminders and clear explanations about past Bunong ways of life, including diet, health, population, livelihood and social structures,” Lan said.

While at the burial site, Bunong community members walked through the woods gathering leaves and wild herbs plucked from the soil. They collected hardened resin from split wood to be used and sold as candles, paints and varnishes.

When the tour was over, a few indigenous community members displayed their bounty on a large leaf. Together, they posed as the World Bank’s communications team snapped pictures.

Correction: This story has been updated at 9:46 a.m. ICT on August 8 to note that Cheth Kimngoy is a LASED III project consultant hired by the Land Management Ministry to implement the World Bank-funded LASED III project. The LASED III representative in the photos is King Vireaksith, senior national environmental risk management consultant, not Cheth Kimngoy, as the captions previously stated.