Bunong people in Mondulkiri’s Roya Leu community say they are gripped by the fear their customary lands will be taken from them.

The indigenous community remains mired in a long-delayed Communal Land Title (CLT) registration process, while Environment Ministry officials, who came to measure lands around the village in late March, appear to be preparing to re-distribute this land to outsiders.

The communities’ fears come as the National Assembly officially adopted the new code of environment and natural resources this week, controversially replacing language recognizing “indigenous and ethnic minority communities” with the more expansive term “local communities.”

Indigenous rights activists have expressed concern the broader term will undermine their long-standing land rights claims based on their unique cultural beliefs and traditions.

Kroeung Tola, a Bunong monitoring officer for human rights NGO Adhoc, told CamboJA that removing the term “indigenous people” would make it easier for others, including authorities, to grab indigenous peoples’ customary lands, impacting their culture and livelihood.

“Indigenous peoples have no other job but to harvest the national resources such as honey, resin trees, and do agriculture on their traditional land. If they lose their land, they will lose their culture and identity,” Tola said.

“Their livelihood is linked to natural resources, and natural resources are linked to their traditions, therefore they are worried about the threats and intimidation from the outsiders,” he added.

The new law may further erode the land claims of the Bunong people in Roya Leu, a community associated with Memom village in Kaoh Nheaek district.

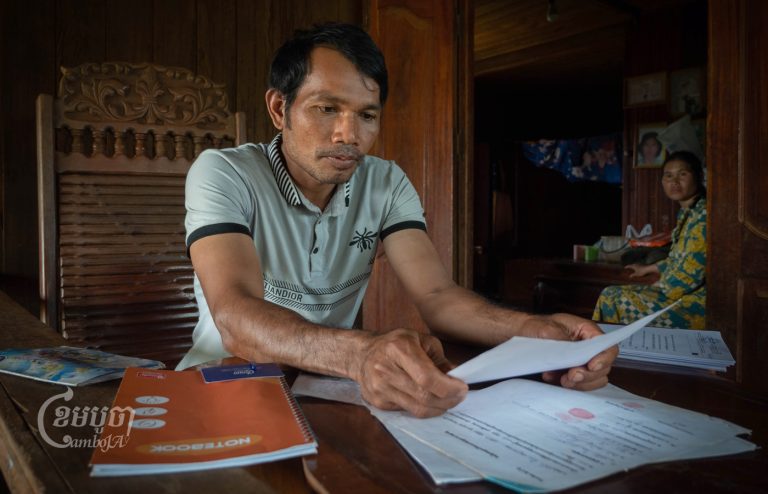

Resident Lin Mao said that the local authorities and a group of students came to measure the forest land on March 31. He believed the authorities planned to give the land to private traders who are not part of the community.

Mao said his community has been struggling to register their community land as part of a typically years-long and expensive bureaucratic titling process that has provided less than 50 CLTs in the past decade.

Mao said his community had requested help from an indigenous rights NGO to “help prepare the necessary documents for the higher authorities to establish a CLT with the aim of conserving natural resources.”

CLTs provide legal protection of indigenous communities’ lands, shielding them from income and food insecurity and legal and illegal land grabbing. Supporters of communal land titles — which incorporate indigenous spirit, cemetery and reserve forests, along with customary farm lands and residential homes into land titles — say the legal recognition preserves communities’ identity and culture through land security.

But the process is slow and can be halted if communities’ requested boundaries overlap with other land claims, such as in the case of economic land concessions or state lands under the control of the Ministry of Environment.

Mao said his community has spent years seeking its communal land title to no avail. He said the administrative work has been expensive and time-consuming, without a clear end in sight.

“We have gone through many processes from commune to district and finally to provincial authorities, but they do not have any solutions,” said Mao, adding that the ministry appears neglectful of the community’s needs.

The community has received recognition from the district level for its self-identity as an indigenous Bunong community, but after many years has still not had its status as an indigenous community recognized on a national level.

As the community waits for legal recognition, government officials have been actively assessing Roya Leu’s customary forest in other ways.

A video, shared with CamboJA by Roya Leu community representatives, shows several men in government uniform in a forest which the community said is part of its reserve forest — community lands set aside for use by future generations.

The ministry has stated it plans to assess land claims within nearly one million hectares of protected conservation area and issue private titles. While these titles may go to communities with long-standing claims, some conservationists are concerned the titling process will be used to cut out forest land belonging to indigenous communities.

After being confronted by Roya Leu community members, one of the uniformed men identified himself as an official with the Mondulkiri Provincial Department of Environment.

“You are measuring forest land, aren’t you?” a Roya Leu community member says. “Samdach’s policy is to measure only unused land and land with crops. And you brought the students here, measuring the forest land or what?”

“We do not know,” the Environment Ministry official says. “We are allowed to come and measure from the environmental department.”

Environment Ministry spokesperson Neth Pheaktra did not respond to requests for comment.

Roya commune chief Pil Deth, who is Bunong, said that the forest in the video is state land which does not belong to the community because they are not yet a legally recognized community at the national level.

“It crosses the line that they protested [the Environment Ministry officials’ presence], because the authorities only measure private land, not community land,” Dith said.

“This community has been seeking for land title for a long time and the commune also supports them but the Ministry of Rural Development does not recognize them yet,” he added. “I do not know what to do either.”

Mondulkiri Adhoc Coordinator Bi Vanny said that forests form the heart of Bunong communities and their connection to ancestral and forest spirits. When the forest is lost, they no longer can maintain their connections to the spirits, he said.

He said that after the passage of the 2001 Land Law, indigenous communities’ connections to traditional forest lands was recognized, in theory. However, the process for obtaining legal recognition of their specific land claims was not finalized until 2009.

“Their aim is to maintain [traditional lands] a sustainable area to gain forest products, not to cut down the forest, but to be able to benefit from it forever,” he said.

Communities which have received CLTs attain strong legal rights over their traditional lands, Vanny said. But the vast majority of legally recognized indigenous communities have not received CLTs.

Mondulkiri Provincial spokesperson Neang Vannak stated that people who make a living by cultivating pumpkins or other vegetables on forested land can receive land titles in protected areas, but the areas largely remain under control of the Ministry of Environment which would be vigilant against people encroaching on the land.

“Sometimes people encroach on this land and do not have the right to cultivate crops,” Vannak said. “As a matter of principle, people have the actual right to use this land for livelihood, but sometimes they abuse it. It is a problem to be solved.”