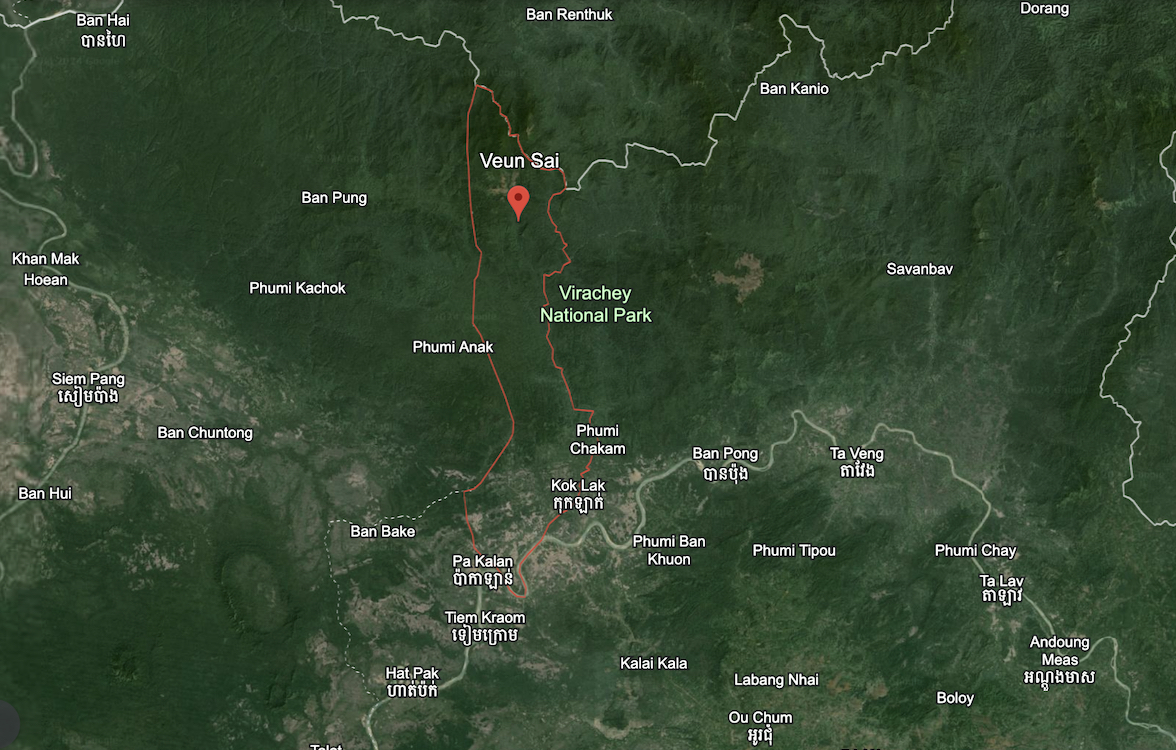

For the indigenous peoples of the Sesan River basin in Cambodia’s far northern uplands, a regional web of interconnected waterways has long been the foundation of traditional life.

“If there is no water, humans and animals cannot survive,” said Veng Many, 29, an ethnic Kroeung woman from Tiem Leu village in Ratanakiri province, just outside the bounds of Virachey National Park.

The Kroeung, as do other indigenous groups such as the Bunong and Brao, rely on the Sesan and other tributaries of the Mekong River for their once-abundant fisheries, as well as for gathering other natural foods and goods.

However, this traditional way of life is on the verge of disappearing as the river ecosystem changes through hydroelectric damming.

Located about 80 kilometers upstream of the Lower Sesan 2 dam on the Sesan River, the Tiem Leu villagers’ cultural heritage of subsistence-based livelihoods has gradually eroded due largely to the varied effects of hydroelectric dams in the wider basin. With the Yali Falls dam in Vietnam and a series of cascading dams already in place upstream, along with the massive Lower Sesan 2 dam downstream, the riverine culture of the Kroeung and other indigenous peoples has been pressed to the limit. Now, two more dams reportedly in the process of being approved for construction could push what’s left of the natural fisheries past their breaking point.

Though most of the area’s electricity on the grid comes from hydropower development, many in this region still use home solar or even car batteries for their low levels of household energy consumption. Meanwhile, residents of Tiem Leu said they receive no irrigation benefits from the various Sesan dams, instead finding themselves manually hauling water from the river as they become more reliant on farming to make their living.

Phan, another resident of Tiem Leu who is now in his 60s, has been a fisherman there since he was a boy. He spoke at length about illegal fishing and, given the sensitivity of his comments, his name has been changed. Nowadays, Phan often finds himself buying fish, many of which are raised in farms, from a vendor who carts them in on a motorbike. This would have been unheard of in earlier generations, Phan reflected.

“There was no selling fish in the time of [my] parents – the villagers always shared with their neighbors when they had the fish,” he remembered.

On a recent visit, CamboJA found villagers struggling to catch any fish at all. The villagers still depend on the river to provide irrigation, as well as for vital household tasks such as drinking and cooking, as well as bathing and laundry. But with hours of work with nets producing little to nothing in the way of food or income, villagers are increasingly switching to farm cash crops such as cashew and cassava.

According to local media reports from the Stung Treng provincial Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, the estimated annual catch has decreased in recent years from as much as 6,000 tonnes between 2018-20 to about 4,000 tonnes or less in 2022. The statistics mirror wider estimates in Cambodia of an approximately 20% decline in natural fisheries catches from 2019-21.

Meanwhile, what remains of the natural fishery is being further damaged by illegal fishing methods – mainly the use of electroshock generators to indiscriminately kill aquatic life – and pollution from human settlements along the water.

Though such methods have long been used in the area and elsewhere in Cambodia to quickly catch more fish at the expense of river ecology, their effects are particularly felt as stocks decline.

This environmental decline has pushed the Kroeung of the Sesan River to adapt. Today, many have already been forced to leave indigenous livelihoods behind, transitioning from subsistence practices to the market and cash-labor lifestyle practiced elsewhere in the country.

These changes can be difficult enough already. But the ecological degradation of the river also has a deeper cultural impact as well, given the spiritual and material connections of indigenous peoples to the land.

“Some (deep pools) are sacred places where we believe there are ancestral spirits that help to guard the people and fish,” said Yun Mane, a representative of the ethnic Bunong and executive director of the Cambodian Indigenous Peoples Organization. “Whenever perpetrators do any ill activities harming the water resources, it makes indigenous people unable to support their livelihood [or their culture].”

A history of disruption

Much like the Mekong, the Sesan River has undergone a mounting series of challenges due to hydroelectric damming.

The first major dam, at Yali Falls, was built in 1996 on a Sesan tributary about 80 kilometers upstream from the Cambodian border, displacing about 8,500 people in the Central Highlands of Vietnam. The dam, which holds a 64.5-square-kilometer reservoir, has been criticized by conservation groups such as International Rivers for its impact on “tens of thousands of villagers once dependent on the abundant resources”.

“Since 1996, the dam has altered the flows of the Sesan River, decimated its fisheries and ruined the lives of villagers dependent upon it in both Cambodia and Vietnam,” the group stated.

While indigenous communities in Ratanakiri had already experienced negative effects from the Yali Falls installation and a later series of upstream cascading dams, the downstream construction of the Lower Sesan 2 hydroelectric dam brought even more dramatic changes to local fisheries.

The Lower Sesan 2 dam is Cambodia’s largest with a total capacity of 400 megawatts, and was built under an $816 joint venture of Hydrolancang International Energy, which is a subsidiary of the China Huaneng Group, and Royal Group of Cambodia. The state-owned utility Vietnam Electricity also holds a minor stake in the dam. The facility began generating power at the end of 2017 and was fully operational by the next year, reportedly accounting for about 20% of the country’s total energy production.

But the dam has been mired in controversy from its earliest days due to its large societal and ecological impacts.

Human Rights Watch has accused the dam of hurting the livelihoods of tens of thousands of other people both upstream and downstream by “likely contribut[ing] to decreases in fishery yields across the entire Mekong River system.”

Ian Baird, professor of geography and Southeast Asian studies at the University of Wisconsin in the U.S., has spent decades researching the Mekong River and its communities. With a speciality in the borderlands of Cambodia, Vietnam and Laos, Baird said he’s visited Tiem Leu many times.

Though the expansive reservoir of the Lower Sesan 2 dam doesn’t reach the village, Baird said the dam cuts off vital fish migration routes.

Some of the area’s most iconic species, such as the endangered giant Mekong catfish and the giant barb, are migratory. But so too are many that humans still depend on for food, such as smaller species known in Cambodia as trey pra and trey riel.

Though the upstream dams in Vietnam are more likely to account for the erratic water levels, Baird believed the large downstream dam was the main reason for the emptied nets in the waters around Tiem Leu.

“There is a fish ladder [at Lower Sesan 2], but it does not work well,” he said. “Many of the fish that they used to catch there migrated from below the dam.”

Baird also said the fisheries have been damaged by hydrological and water quality changes due to the dams in Vietnam as well as illegal fishing, “especially electricity fishing”.

Attempts to restore the fish species of the river will likely be futile as long as the dams are in place, he added.

“The best way would be to remove the Lower Sesan 2 dam,” Baird said. “In the United States, many dams are presently being removed to restore rivers. Releasing fish into the fish is unlikely to work well.”

Illegal fishing practices deepen the crisis

As the dams appear to degrade the riverine ecosystem, some people have added to the decline by resorting to illegal and destructive fishing methods. Much of Cambodia’s system of community fisheries, a localized, nationwide attempt at managing natural resources, is dedicated to stopping this kind of behavior.

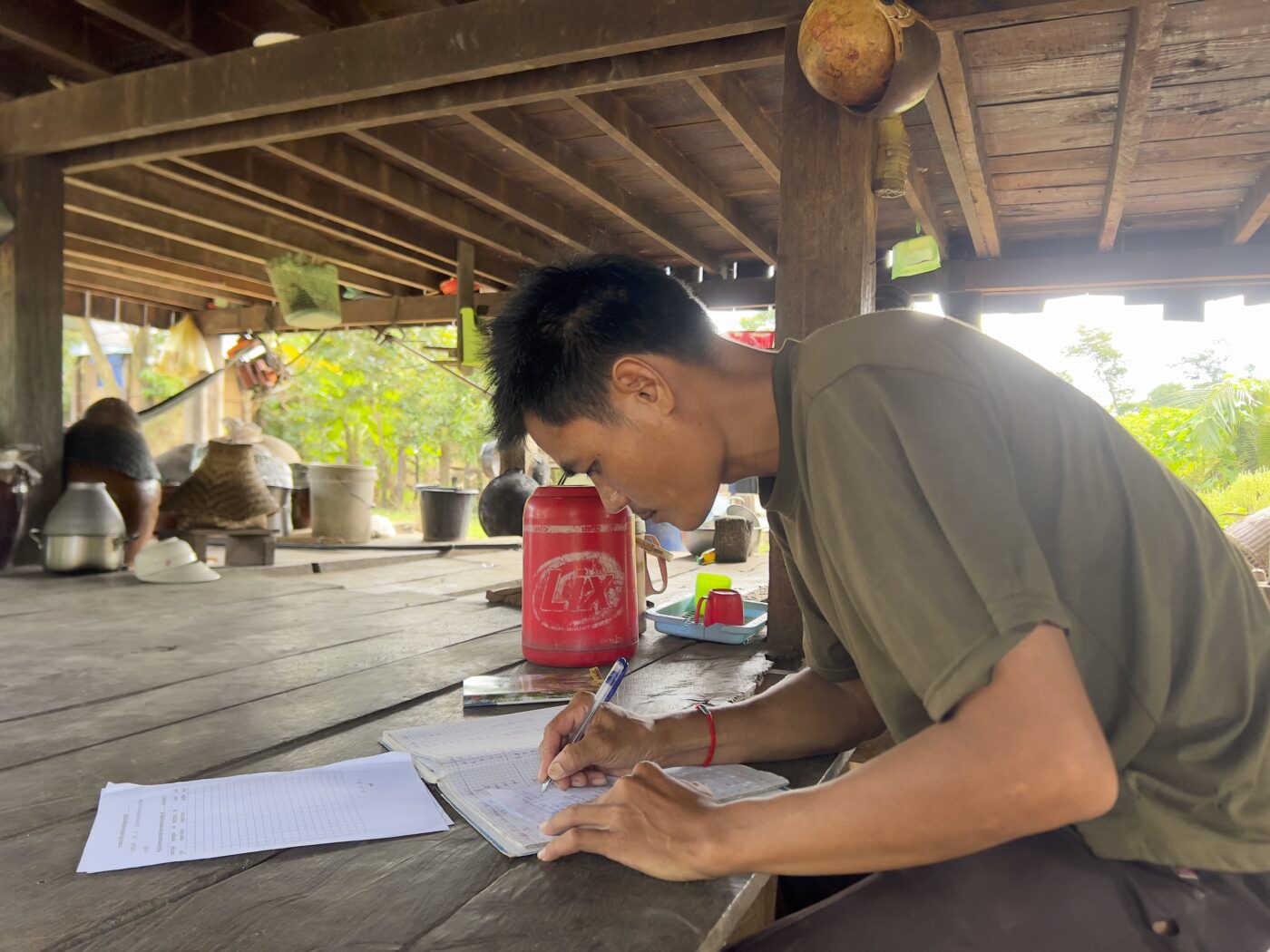

“We want to protect the fishery industry because the fish is our food base and we also can get some income from selling [them],” said Bun Kiet, head of the Ka Chon and Kok Lak fishery community in Tiem Leu, who conducts overnight patrols with other community members. “There are a lot of perpetrators at night because there are at least two [illegal fishing boats] per night.”

However, he and his team have never seen the illegal fishing boat recently whenever they go patrolling.

“[I] do not know that they [perpetrators] know before we go or not because we have to report to the relevant official such as commune officials whenever we go patrolling,” Kiet said.

Meanwhile, those who still fish legally, such as Phan, increasingly see little point.

Phan spoke to a reporter while he was busy working with his gear. He uses roughly 10 fishing nets but may get only three or four fish nowadays, if not coming home empty-handed. Though the fishery decline has been happening for over a decade, he said the past three years have seen his catch become even worse.

“It is not the normal citizen who commits [illegal fishing], it is the police who do it,” Phan asserted. “We are poor and we are afraid of [lawsuit]. They are rich so they care nothing.”

Phan’s claims about police echo common accusations in rural Cambodia of collusion between local officials and perpetrators of wildlife crime. Though arrests are widespread in natural fisheries, so too are the alleged infractions – authorities recorded 2,952 cases of illegal fishing practices in 2021 and nearly the same number as the year prior.

Government spokesperson Pen Bona declined to comment on the building and the impact of the dam and referred questions to the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries.

Responding to queries on restoring the fishery, Khim Finan, the ministry’s spokesperson, said there has been neither specific nor informal study regarding the decline and said damming was not under the purview of his ministry.

“We also do not have the basics to draw conclusions on [the fish shortage],” Finan said.

Erratic water levels, lack of information

Along with the fishery collapse has come erratic fluctuation of the river’s flow. The villagers told CamboJA they receive only little information about the timing of dam openings and closings. In May, they experienced an abrupt swing in the river’s level that startled the residents in its suddenness.

“We did not know because they did not provide any information,” Many said. “[It’s] like we’re living in the forest – we get nothing.”

The unpredictable water levels have killed off both natural and cultivated vegetables along the banks, Many said, and villagers are concerned that a sudden rise could flood their homes.

She explained that locals get information about dam gate openings from a Telegram group called Sesan River Community Network, that includes members from the districts of Andoung Meas, O’Ya Dav, Ta Veng and Veun Sai. But the warnings distributed through this channel come only briefly before the actual opening, leaving little time to prepare for possible flooding.

“News transmission is late and rushed,” Many continued. “For example, if there was a flood, we would have nowhere to go – and how would we gather our wealth, such as pigs and chickens? If they inform us three or four days beforehand, it would be fine.”

However, according to Many, local officials have not been supportive of her and others’ efforts to disseminate information about the upstream dams, hoping to prevent public anxiety about them.

Sveng Bann, the Tiem Leu village chief, acknowledged that local fisherfolk “cannot catch enough fish for consumption”, but said they could if they “put more effort into fishing”.

Veun Sai district governor Heng Savouern dismissed Many’s claim that local authorities prohibited conversations about dam impacts in public discussion. But he also rejected the notion that the fishery had degraded in recent years.

“There are a lot of fish, even more (than before),” Savouern said.

Struggling to adapt

As villagers along the Sesan worry about protecting what they have, many find themselves spending more money – with little in the way of additional income.

Cashews and cassava are the main cash crops, but a strong harvest often depends on irrigation systems that tend to be less developed in indigenous villages where such practices are relatively new.

Last year, Many said, her family earned 1 million riel, only about $250, from selling cashew.

Even still, the community hasn’t given up on the river yet.

The fisherman Phan beseeched authorities to put a stop to illegal fishing, hoping for a future where the fishery could be somehow restored to as it was in his parents’ time.

“There are less fish due to the dams, and this results in some people becoming desperate and using illegal fishing gear. Electric fishing can negatively impact fish populations by catching too many fish,” said Baird. “[Fisherfolk] are desperate due to fish declines.”

Looking even further down the road, Many said her peers in the village are opposed to the construction of more dams in their area. As authorities make little to no information about hydroelectric projects publicly available, she feels that local people are left in the dark. Similar to Phan, she urged authorities to consider the fate of river villages such as Tiem Leu when considering future development.

“If they hear and know [the bad impacts], please help to reduce building the dams,” Many said.

“Reporting for this story was supported by Internews’ Earth Journalism Network”.