Nine Boeng Tamok lake residents face charges of “intentional acts of violence and obstruction of public officials” and were placed under court supervision following a February 21 warrant issued by the Phnom Penh Municipal court.

The residents received the warrant in the morning and were ordered to appear in court by the afternoon. They did not attend because their lawyer from human rights NGO Licadho was unavailable, they said.

Court spokesperson Y Rin said there was no further information to share and Lim Sokuntheara, the judge who issued the warrant, could not be reached for comment.

For years, the outspoken residents of Samraong Tboung village on the outskirts of Phnom Penh have protested the filling-in of Boeng Tamok, one of the capital’s last remaining natural lakes. They are also on the verge of being evicted from their homes and losing their livelihoods fishing and harvesting vegetation from the lake as a series of land giveaways to well-connected elites and developers transform the landscape.

Prak Sophea, a prominent activist and resident of Samraong Tboung village along the lake, denied the allegations. She said the charges likely arose after an altercation between authorities and residents in October last year.

Local authorities had barred residents from making home repairs on the grounds they were illegal squatters and gave them packs of noodles as compensation. A group of frustrated villagers later burned the donated gifts in front of village security officers, who kicked the embers at them. In response, the villagers threw rice. The embers burned Sophea and forced her to visit the hospital for treatment, she said.

“Should we stand for the authorities to beat us, can we not defend ourselves?” said Sophea, a 43-year-old mother of three. “Does the law allow us to protect ourselves or let the authorities beat people?”

Committing an “intentional act of violence” carries a maximum of three years imprisonment and a six million riel fine, while “obstruction of public officials” could lead to a one year prison sentence and two million riel fine, according to the Cambodian criminal code.

Sophea and at least 10 villagers have already been ordered to appear in court a combined three times since 2022.

The Phnom Penh Municipal Court previously issued a court summons in August 2022 for seven representatives of Samraong Tboung village, including Sophea. The Prek Pnov district head of security claimed the residents had committed obstruction of public officials, incitement and public disorder.

Soeun Sreysoth, 32, said herself, her husband and her brother were named in the most recent court summons. She added that she is disappointed as they had merely sought to raise their voices to secure legal land ownership of property they have occupied for years.

“It is injustice for citizens because we are just advocating, fighting for our housing rights, but the authorities issued a warrant to threaten us,” she said.

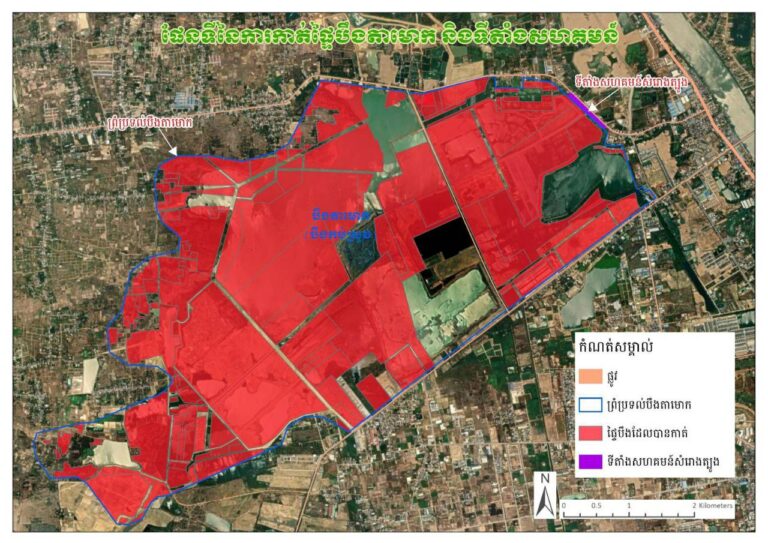

According to urban poor NGO Sahmakum Teang Tnaut (STT), at least 2,244.45 hectares of the lake’s 3,239.69 hectares have been filled in with sand, following a 2016 sub-decree allowing the government to rent or sell land in and around the lake.

In recent years, filled-in areas around Boeng Tamok lake have been distributed to wealthy and powerful individuals and companies. Recipients include ruling party CPP senator Kok An, Chea Sophalen, the daughter of Land Minister Chea Sophara, military commanders Vong Pisen and Sao Sokha and the famous singer Preap Sovath.

Out of many companies, the director of Orkide Villa, Nuth Ton also received 67 hectares of Boeng Tamok lake in September last year. Orkide is chaired by Prime Minister Hun Sen’s daughter Hun Mana, while his other daughter Hun Maly and daughter-in-law Pich Chanmony are also directors in Orkide-brand firms.

Samraong Tboung villagers have not received any land titles or been classified as legal residents but they have always been able to vote for elections, they say.

Soeung Saran, STT’s executive director, said he appreciated development around Phnom Penh but not without consideration of its impact.

“Before developing, we should think about the long-term impact on society and the environment,” he said. “I would like to see more assessments of the social, economic, and environmental impacts before making a decision to modify the land.”

Am Phoeun, a mother of four named in the August 2022 court summons, said that while she has making a living fishing from the lake since 2007, she is now preparing to migrate to Thailand to find another source of income.

“Due to the development and landfill of the lake, We don’t have an income except to decide to migrate,” she said. “We used to depend on fishing, but when the authorities landfill the lake, my family and I got a big effect from it.”

Sophea, she asked the government to find justice for citizens and to let them live where they are because she thought that she would get enough income by living here, such as by selling drinking water.

“We have lost income from development, so we want to live in the development area,” she said. “We can do business [there].”

“We are deeply hurt and frustrated by the authorities,” she continued. “It is one of the most unfair things that the people of the lake have no right to live there while only high officials, companies and institutions have the right to live there.”