Picture a modestly sized house with ample rooms for a burgeoning family. Outside, we find a manicured garden and a driveway for the family’s two cars. For a growing number of Cambodian urbanites, this vision is the ideal living environment they strive for.

To satisfy this demand, real estate developers are selecting locations farther and farther away from Phnom Penh’s urban core. The overwhelming majority of new housing projects are located in peripheral districts like Sen Sok, Chbar Ampov, Dangkao, and Por Senchey.

However, this model for housing may not be as flawless as it first appears. The city’s rapid suburban expansion has had several negative effects on its inhabitants, municipal resources and environment as a direct result of car-dependency.

Car-dependent sprawl

Phnom Penh is rapidly expanding outward through low density construction, making residents more dependent on cars. In the long term, it will be destructive—in terms of the financial losses, environmental degradation, and health implications for Phnom Penh’s population.

Whether individual developments are well-designed or not, the fundamental nature of low density development means that schools, grocery shops, offices, restaurants and parks are farther apart and farther from people’s homes. Furthermore, the poorly laid-out street network of outlying districts is causing neighborhoods to be disconnected, requiring commutes to be circuitous and inefficient. This means residents often must use private vehicles for even the most basic necessities.

Low density sprawl also makes it difficult for municipalities to maintain infrastructure and services. Road surfaces, electrical lines, clean water pipes, garbage collection and sewage—just to name a few—are dependent on optimal city density. For example, a high density neighborhood, with more residents sharing the financial costs of maintenance, reduces the cost per capita.

Car-dependency pushes urban sprawl deeper into former wetlands, lakes and farmlands, damaging the natural environment right outside of Phnom Penh. Driving makes commuting farther much easier, which makes living farther away seem more reasonable. This in turn pushes the demand for urbanization farther outside the city’s boundaries.

A built environment designed for cars makes other commute options less attractive. A study in the city of Changchun, China, for instance, revealed that inhabitants make the decision to use cars as their primary means of commute on the basis of the built environment around them. Factors including neighborhood density, the availability of mixed-use development and the distance to the city center all contributed to their decision to primarily travel by car.

More driving means more danger

Apart from the often discussed environmental and financial drawbacks of using private vehicles, car accidents are an even more concerning and often overlooked public health issue.

Car-dependency is killing and maiming us directly through traffic accidents. The Ministry of Public Works and Transportation reported 1619 accidents nationwide for the first half of 2020, with 861 fatalities and 2449 injured. Although the country saw a noticeable decrease in crashes and casualties in 2021, at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, rates rebounded in the first half of 2022, with 1609 accidents nationwide, 942 fatalities, and 2235 injured.

Although it is tempting to place blame solely on poor driving or lack of enforcement mechanisms, policymakers must be aware that high accident rates are also a direct result of more people driving and street designs that fail to protect vulnerable road users.

Death and injury from crashes are only the start. The lack of physical activity that a car-dependent lifestyle enables is also indirectly harming us in an insidious way.

Physical inactivity has been linked to an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases, obesity, and diabetes. Health experts suggest that adults should do at least 30 minutes of physical activity daily for at least five days a week, including walking and cycling.

Walkable neighborhoods make active commuting and public transit usage both convenient and attractive options for residents. In a walkable city, inhabitants get their daily dose of physical activity just by commuting to and from work, school or the grocery store.

Conversely, the same cannot be said for a resident of Phnom Penh’s car-dependent neighborhoods, where the absence of pedestrian and cyclist infrastructure makes it very difficult to rely on active commuting. Residents in Cambodia’s capital often choose to drive just to buy a cup of coffee.

Taking car traffic out of our neighborhoods

The factors mentioned above can be rectified through better urban policy and intentional design. There are a few key approaches that would help Phnom Penh get to a healthier, more sustainable way of living and moving.

First, Phnom Penh’s city planners should adopt a compact city approach to urbanization. This would involve constructing dense, mixed-use neighborhoods with dwellings, schools, public spaces and places of employment that are scaled for walking rather than for cars. Ideally, these spaces would be well-connected by foot and cycling paths, and served by excellent public transit infrastructure. A compact city approach would discourage development that sprawls far beyond Phnom Penh’s current borders.

To help drive compact development, several policies in particular should be prioritized. Most crucial are land-use concepts like Transit Oriented Development (TOD), which encourages the development of mixed-use neighborhoods within walking distance of public transit stations. There must be efforts to optimize street networks and road design to serve active commuters as well.

Phnom Penh should look to cities around the globe for creative solutions to some of these problems. Our city could, for instance, look to the low-traffic neighborhoods initiative in London, in which streets in residential areas are being redesigned to restrict car traffic and prioritize active commutes. Researchers from the U.K. think tank Centre for London recently examined data from 10 low-traffic neighborhoods and found that cycle use rose by between 31% and 172%, while car traffic fell by between 22% and 76%. There was also strong evidence that these schemes reduced road casualties.

Or Phnom Penh could look to Barcelona’s superblock schemes, which not only ban automobile through-traffic from non-resident drivers but also add much needed green space to neighborhoods.

“It was amazing when they stopped the cars,” Barcelona resident Norma Nebot told Vox in 2019. “The feeling of being with my kids, playing in the middle of the road, that was incredible.”

These schemes could be replicated in Cambodian cities with local needs in mind, encouraging more commuters to ditch their cars for short trips and use more active means of commuting.

Redesigning roads for greater health and safety

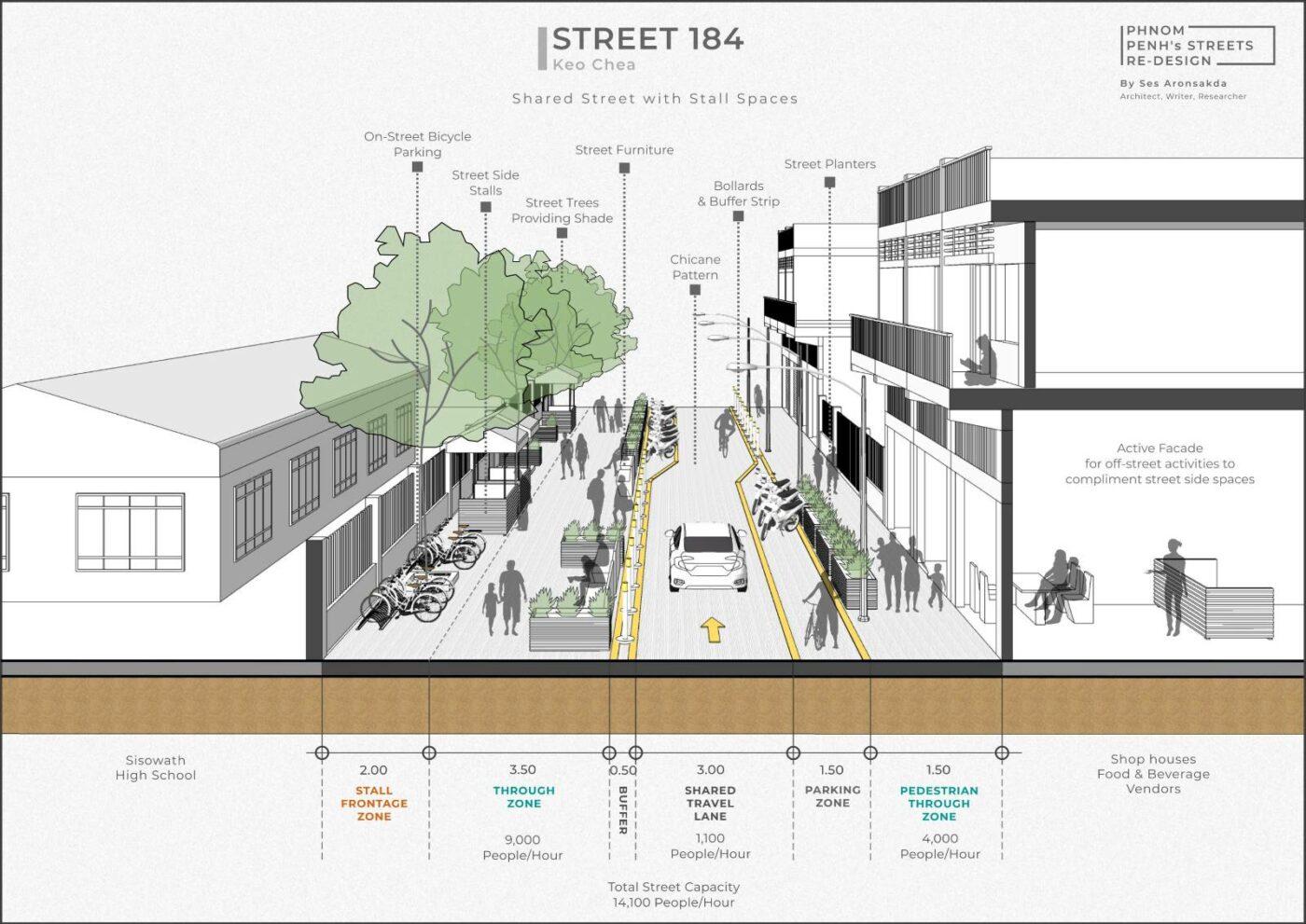

Road diets would also complement efforts to make Phnom Penh’s streets safer. This involves reducing driving lane width, decreasing the number of lanes, implementing one-way streets, and using vegetation and street furniture to force a slower driving speed.

Yet, rehabilitating the dysfunctional street network of Phnom Penh on a case-by-case basis alone will not be enough. Without taking systematic action on congestion, cars and motorcycles will inevitably clash with the active commuters and public transit.

Phnom Penh should undertake a process called disentanglement to separate different modes of commute from each other. This strategy would involve carving out separate lanes and streets for public transit, motorcycle users and pedestrians. Disentangling urban traffic would not only increase efficiency, but also boost safety, as each mode of transportation would not be forced to compete with the others on the road.

Such a transformation may seem daunting and disruptive. However, Paris has shown that changes to a city’s street network can be done quickly and at a low cost.

By making use of movable planters, paint and bollards, Paris’ bike lanes were set up originally in 2019 when public transit staff were on strike. The lanes helped alleviate disruptions, and were later expanded during covid-lockdowns to help curb infections.

Parisian authorities continued with the rapid expansion of 650 additional kilometers of bike lanes through temporary interventions, using movable planters and bollards. This allowed Paris to rapidly pilot a new public transportation scheme, dramatically improving mobility and increasing ridership.

Phnom Penh could use some similar approaches to turn its car-dependent suburbs into human-centric living spaces.

Car-free suburban neighborhoods

It is crucial that Phnom Penh’s suburbs reverse car-dependency as soon as possible because of the harm it is causing citizens, local authorities and the environment.

A combination of policies and design changes can steer development to ensure easy access to housing, education, work and other services. New strategies would produce safe and reliable commutes, decreased living costs, and increases in overall public health, while also minimizing the city’s environmental footprint.

Despite being car dependent, Phnom Penh’s fast expanding suburbs don’t have to remain this way. With timely intervention, these suburbs have the potential to become the ideal neighborhoods we envision them to be.

Ses Aronsakda is a research fellow at Future Forum.