Long before Ream Sreyrath, 23, first joined her Stung Treng community’s volunteer fisheries protection patrol, she’d been curious about the work of the mostly male crews who spent long hours cruising the Mekong River.

“When my father, who is the deputy patrol chief, left his wife and children at home to patrol in the community, I really want to know [about it],” said Sreyrath, a youth leader and student from the riverside village of Koh Khan Din in Stung Treng district.

Sreyrath’s father, Sau Dany, 53, is the deputy head of the Anlong Koh Kang fishing community. He patrolled the area for nearly 22 years, freely giving his time to a crew dedicated to community-level policing against illegal fishing and wildlife crime.

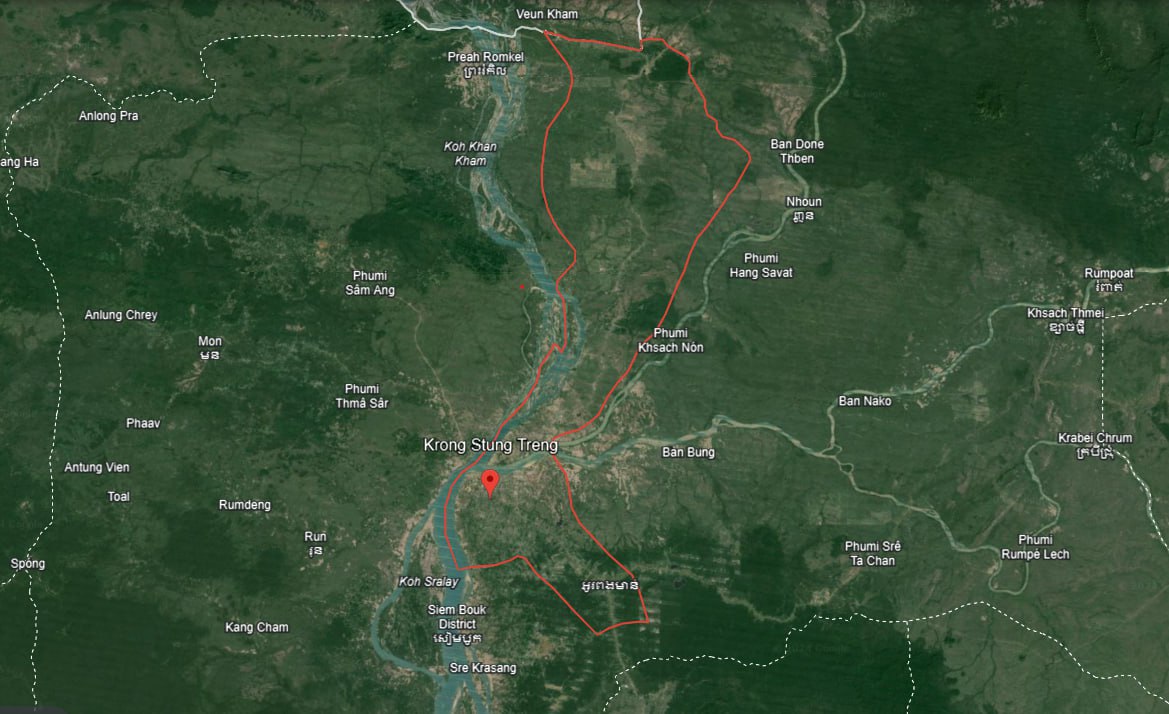

Stung Treng is a rural northern province of Cambodia on the border of Laos, where the Mekong breaks into massive rapids and drops into deep pools that harbor iconic river species such as the giant stingray. People here are no strangers to the big river, with many making both a cash income and daily diet from fishing its silty waters.

Given the importance of this natural resource to rural people, community fishery groups work with local police and environmental officials to prevent illegal fishing, which includes fishing during breeding season or in protected areas, as well as the use of explosive or electroshock devices, poisons and certain kinds of nets.

Cambodia has stood out for its governmental strategy of promoting localized, small-scale fishery management, which reflects the national reliance on fish as a main source of protein. As of 2015, the state recognized 507 community fishing institution (CFi) organizations, a number that includes Anlong Koh Kang and other volunteer fishery patrols across the country.

For years, Dany’s crew was mostly made up of men. But in Koh Khan Din, and in the neighboring stretch of rural fishing villages, young women such as Sreyrath are stepping up with hopes of contributing to local conservation efforts in a meaningful way. In this part of the country, local nongovernmental organizations say more women are participating in such work than ever before – however, women themselves say they’re still limited by wider Cambodian cultural expectations about gender that can restrict their role in community work.

Mam Kosal, a community fisheries expert with the nonprofit international conservation group WorldFish, said Cambodia stands out in the region for relatively low levels of female participation. From his observations on the community level, he made a “conservative estimate” of women making up about 10-20% of local volunteership.

“In Myanmar, the level is much higher – I engaged in many events when women represented no less than 60% in any task related to fisheries management,” Kosal said. “In Laos, about 50% of women participation has been observed in many consultations I organized. For the latter two, they did not only join or attend, but did participate.”

Kosal expanded on the distinction between attendance and participation by saying that women in Cambodia may sit in on meetings to replace their male counterparts if they should be busy with farming or other tasks, but aren’t expected to take a permanent role in decision-making.

Besides leadership positions, fieldwork is also generally seen as the domain of men. Though a spokesperson for the Ministry of Environment said the government has a working group to promote gender equality, they also said that last year there were only 38 women among the ministry’s 1,069 total park rangers.

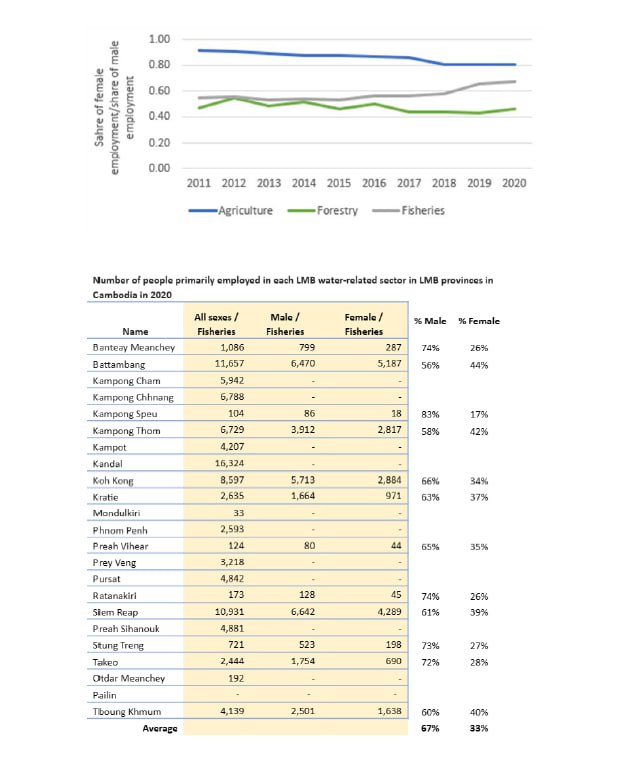

Fisheries management lies under the purview of the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, where a spokesman also said there are initiatives to promote gender equality but provided little detail. According to data from the Mekong River Commission (MRC), an intergovernmental organization dedicated to management of its namesake river, employment in the Cambodian fisheries sector as a whole skews male in a similar fashion as community patrolling.

In 2020, women made up about a third of the fisheries workforce, stated the MRC, with men accounting for the remaining two-thirds. Stung Treng had even fewer female fisherfolk, with women making up an estimated 28% of fishing workers.

Regardless of gender, fisheries workers are now vying for what they say is a dwindling catch.

According to local media reports from the Stung Treng provincial Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, the estimated annual catch has decreased in recent years from as much as 6,000 tonnes between 2018-20 to about 4,000 tonnes or less in 2022. The statistics mirror wider estimates in Cambodia of an approximately 20% decline in natural fisheries catches from 2019-21.

Stung Treng province has 62 fishing communities listed with the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries that cover a total fishing area of more than 492 square kilometers. While damming, climate change and other factors are also pressuring fish populations, illegal fishing historically has made these problems even worse.

In the Tonle Sap Lake, Cambodia’s largest natural fishery, illegal fishing operations can pull in an estimated 500 kilograms of fish in a day. Across the country in 2021, Cambodian authorities recorded 2,952 cases of illegal fishing practices, nearly the same number as the year prior.

Villagers in fishing areas typically regard illegal fishermen as coming from outside of their own communities, sometimes using electroshock equipment from Vietnam. But past investigations of Mekong fishing have found that locals partake in such activities as well, and that electric fishing gear is readily available in Cambodia. Though there are penalties for illegal fishing, it’s unclear if they present a real deterrent.

Srey Sornvichet, chief of Stung Treng provincial Fisheries Administration, said that “law enforcement is both soft and hard”.

“When we catch them committing illegal fishing for the first time, we call them to educate, advise and to stop them from doing it again,” he said. “If the offense is serious, such as the use of electricity, explosives or poison, we will bring the perpetrators to court to follow the procedures of the law.”

As a whole, Cambodia receives consistently low ratings for governance and rule of law from civil advocacy groups such as the World Justice Project. Meanwhile, the annual Corruption Perceptions Index from rights organization Transparency International annually ranks the kingdom as among the world’s most corrupt states.

Against that backdrop, community groups help to fill what otherwise might be a shortage for local resources management.

Nongovernmental organizations such as the Culture and Environment Preservation Association (CEPA) have worked closely with government agencies to promote community fishery initiatives.

Vi Phal Luy, provincial coordinator of CEPA for Stung Treng, said natural resource management “motivates young people” but that community groups still “need the participation of the authorities [and] civil society organizations to gather professional ideas.”

According to CEPA, the Stung Treng community fisheries are overseen by a total of 452 management committee members, 114 of whom are women.

Kohn Somdon is one of them. She serves as the secretary of Koh Sneng fishing community and lives in an ecotourism area in Koh Sneng village, of Stung Treng’s Borey O’Svay district.

“Although the patrol was difficult, I still wanted to join because I want to participate in the development of my village and conserve the resources in our river, as well as to challenge myself,” Somdon said. “I want to know, want to hear and I want to help, as a woman.”

At the same time, Somdon and other women who spoke with CamboJA said their female perspective wasn’t always welcome in management activities. And though patrollers such as Somdon said it was important to them to participate as much as possible, women are often excluded from certain community fishery jobs, according to the WorldFish expert Kosal.

“Women generally are involved more in identifying issues, bookkeeping, reporting of offenses, as well as in planning, but are less active in patrolling and law enforcement,” he explained. “This should be seen as [tapping] deep into the Cambodian culture and tradition, in which women normally have their domestic work or tasks that restrain them from traveling far from home.”

These male expectations for women to take care of housework and children, Kosal added, often in addition to running small businesses and other income-generating work, limit time to engage in tasks such as community fisheries management.

These expectations are familiar to Kan Hakunthea, 31, a volunteer from Svay Rieng village in the Sesan district of Stung Treng. She first got into community fisheries work about 15 years ago, when she was just a teenager, and has been involved ever since. Today, she balances her passion for conservation with her other work, as well as her family and two children.

“The main reason I joined is because I love and want to help nature – and especially want to let people know that women can do it too, because in most areas they are treated with contempt,” Kunthea said.

However, she found an evolving set of misogynist assumptions from her peers about her work on the water. Though they haven’t kept her from participating, Kunthea felt that other villagers were discouraging women on the water.

“When I was single and patrolling, people accused me of going out to [to date] young men, not actually going to patrol,” she said. “And when I got married, they said I do not know how to manage the family well.”

Such attitudes persist, according to relative newcomers such as the 23-year-old Sreyrath. But, with an increasing focus on gender equity from nongovernmental organizations and quasi-governmental groups such as the transnational Mekong River Cooperation, there may be an increasing push for change.

Kosal, the WorldFish expert, said the education and experiences of women count for a lot if they are to participate in deliberation and other activities.

“They do need to get exposed long enough to such events to gain lessons and experience to enable active and meaningful participation,” he said.

For Sreyrath and other women, there are still clear barriers to some of these experiences. But the female patrollers who spoke with CamboJA said they would not be deterred by any adversity.

“In the future, I would like to see [even greater] participation of women, even if they do not go on patrol, but play a role in outreach or making reports,” Sreyrath said. “Motivation pushes women to participate [themselves] as well as to promote other women’s participation.”

This story was produced with support from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.