More than a decade after subsidiaries of multinational rubber firm Socfin Group forcibly cleared and seized the farms, burial grounds and sacred forests of Bunong indigenous communities in Mondulkiri province, the company now seeks to collect tens of thousands of dollars from these farmers for the cost of “land preparation” and other fees.

Beginning in 2007, the Cambodian government awarded several economic land concessions for industrial rubber farming to subsidiaries of the Luxembourg-based Socfin Group, whose corporate slogan is “responsible tropical agriculture.” The company’s Asia subsidiary Socfinasia— which includes all its Cambodia-based rubber plantations — reported profits of more than $75 million last year.

In Mondulkiri, upwards of 800 Bunong families across seven villages were impacted by concessions encompassing more than 12,000 hectares in total. Throughout Cambodia, traditional indigenous land use rights have consistently failed to be recognized, leaving communities vulnerable to land grabbing.

Some Bunong villagers remain embroiled in a legal fight against Socfin’s largest shareholder Bolloré. Yet 210 families who chose to negotiate with Socfin subsidiaries completed a years-long mediation process in 2021, which was funded and supported by the German, Swiss and Luxembourg governments and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR).

The mediation led to settlement agreements for five villages in Bousra commune, with Socfin promising to invest in small amounts of infrastructure, provide development funds to some families in compensation for lost lands, and leave intact the remaining Bunong cemeteries and spirit forests.

Human rights organizations and other Bunong residents of Bousra have criticized the mediation’s outcome as legitimizing a land grab violating indigenous peoples’ rights, though some families who participated in the negotiations say they felt the mediation was better than losing their land and receiving nothing in return.

But the years of mediation never resolved a long running aspect of the dispute: Socfin still demands tens of thousands of dollars from dozens of Bunong farmers in fees.

“I Was Forced to Accept”

After Socfin’s subsidiaries faced protests and backlash from human rights groups for bulldozing Bunong lands, the company offered more than 850 impacted families several options for compensation starting in 2009. Many unwillingly accepted some form of compensation, according to a 2011 report from the International Federation for Human Rights.

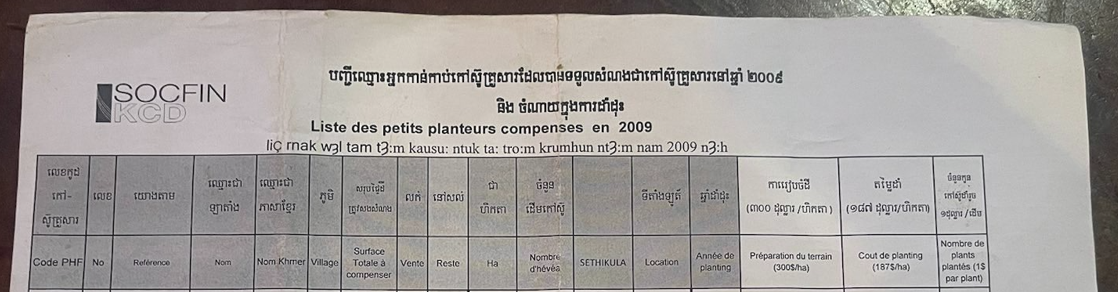

One option at the time presented to Bunong villagers set to lose their farms was to grow rubber inside the concessions as part of what Socfin calls its “family rubber farmland” program. Socfin told CamboJA that 52 families joined the program, receiving technical training and assistance and signing contracts promising to repay the company for the costs of the rubber trees planted on their traditional farmlands. The farmers do not own the land, which remains in Socfin’s control.

Pu Lu resident Nges Nam said he felt he had no choice when signing the contract.

“The company had planted rubber on land that had been cleared and if we didn’t take it, we would lose [land], so we were forced to take it,” Nam said. “I was forced to accept the rubber trees planted on the farmlands. They had already planted them.”

In these contracts, Socfin billed the families for the “cost of planting” at $1 per rubber tree, as well as for “land preparation” and “fertilizer used during the planting” according to two contracts from 2009 and 2014, reviewed by CamboJA. The contract also included hundreds of dollars in “administrative” and “maintenance fees” and added 5% annual interest.

One hectare of farmland typically contains more than 500 rubber trees, Bunong farmers say. Multiple farmers claimed they were told by Socfin that they owed the company more than $10,000 under the original contracts, though most said they were no longer in possession of these contracts.

“Since it had been agreed upon by members of the community at the signature of their initial family rubber farmland contracts to reimburse the investment the company had made to prepare their farmland, it seems only fair that the communities should also honor their commitments, given that they themselves derive income from it,” Socfin said in an emailed statement.

“The company invested [a] huge amount of money to set up the smallholders’ plantations,” added Socfin. “New contracts are currently being renegotiated.”

Socfin said it conducted a survey in July to assess families’ ability to repay and “propose a culturally appropriate repayment method.”

Bunong villagers say Socfin did not agree to waive the interest payments from the contracts during the years of meditation which ended in 2021. The company told CamboJA it had verbally agreed to remove the interest and administrative fees earlier this year. Socfin declined to share the total debt owed by all 52 Bunong families.

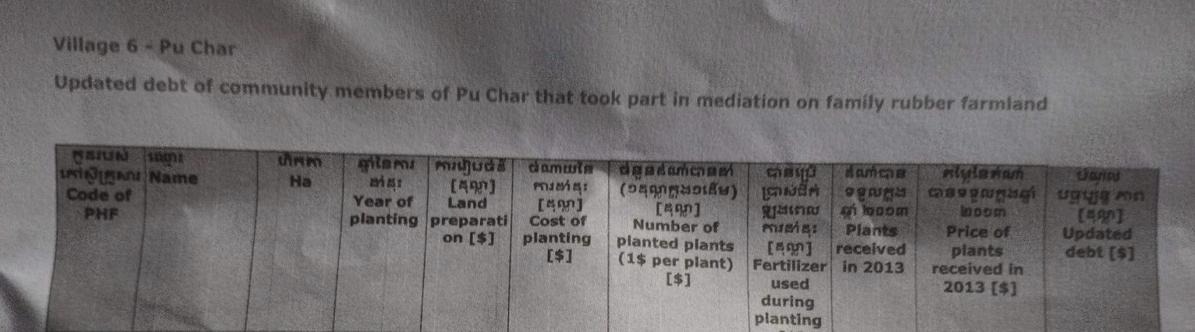

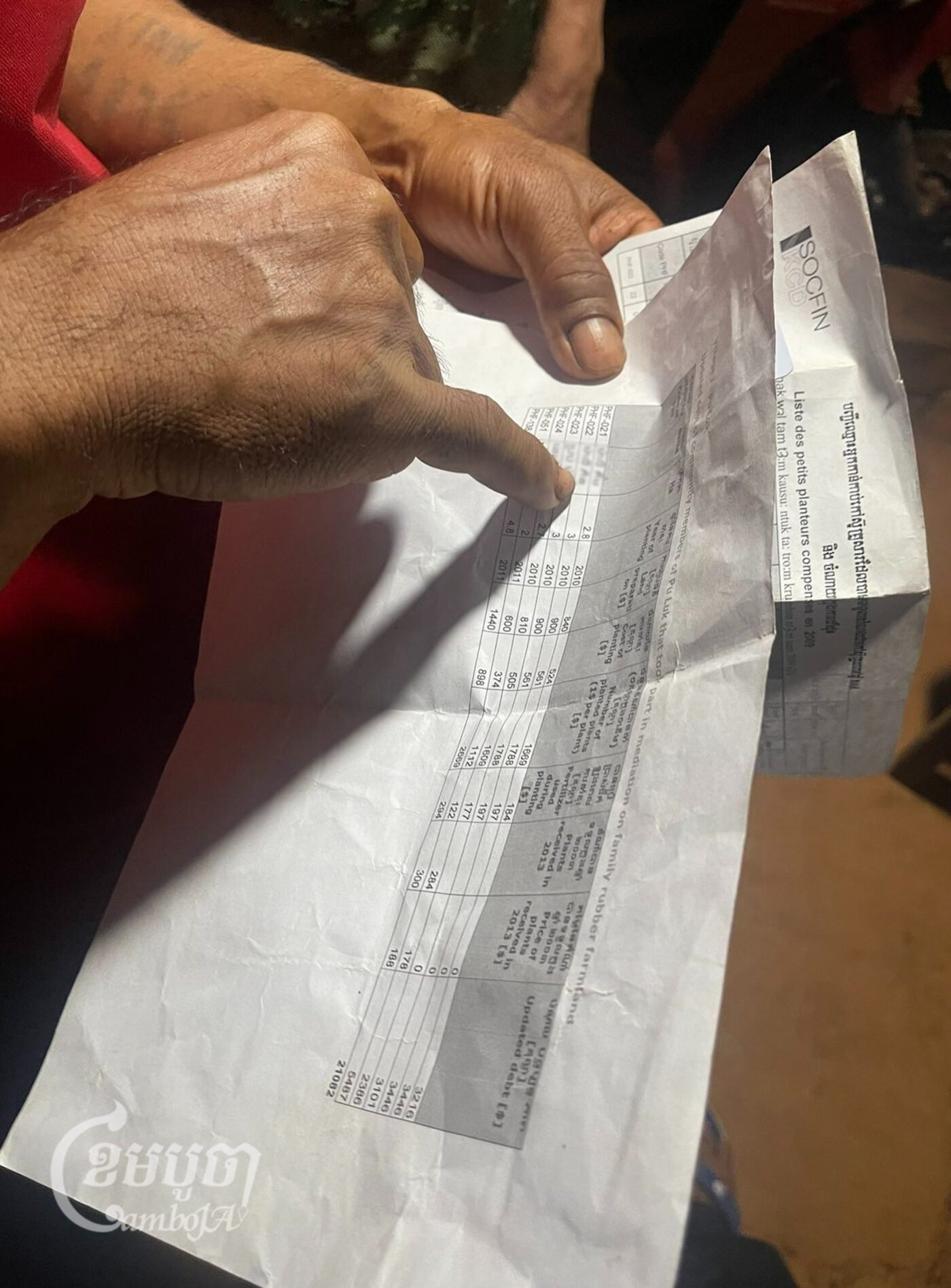

But 18 farmers from Pu Lu and Pu Cha villages, using about 53 hectares of land inside the concessions, still owe Socfin more than $60,000 combined according to documents titled “updated debt” which Socfin distributed to villagers this year. Farmers say their “updated debt” excluded the interest, maintenance and administrative fees — which, if included, would have brought the debt to more than $100,000, CamboJA calculated.

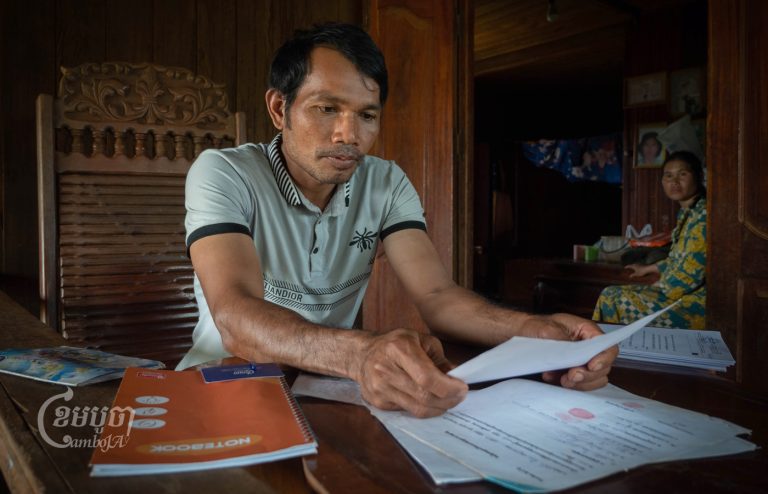

In some cases, Bunong farmers appear to be paying Socfin more than they are receiving in compensation as a result of the overall mediation. Maly Kim, who represented Pu Lu village in the mediation, owes Socfin $3,216 for his rubber farm and is receiving the equivalent of $3,000 over a three-year period for the loss of other farm land as part of a separate aspect of the mediation, documents show.

Several farmers CamboJA spoke with said they would accept new contracts for the family rubber farm program if Socfin follows through on its verbal promise to remove the interest rate and administrative fees. But the outstanding debt still represents a significant chunk of their income.

“We could pay installment payments for five to 10 years, that’s fair, but if the company limits the repayment [timeline] to two years, it isn’t fair,” Kim said. “In my opinion, we are lacking [in income] and if the company forces us to pay, we can’t afford to do so.”

Pu Lu resident Maly Penh, Kim’s older brother, said he makes around $4,000 annually from his three hectares of rubber in the concession and Socfin is seeking to collect $3,446 from him. And Pu Cha village farmer Krek Trill earns around $2,400 a year from his one hectare rubber farm while his debt is projected at $1,500.

When the mediation concluded in 2021, Pu Cha and Pu Lu village signed settlement agreements — as did the other villages, according to Socfin — stating they would continue to negotiate the family rubber contracts with Socfin and that the company would provide new contracts by June 2022. No contracts have since materialized, village representatives say; Socfin says it plans to present a “draft contract” later this year.

Poch Sophorn, a consultant who was paid to oversee the negotiation process, told CamboJA last year via email that making new contracts for each family was “not possible” because it was “time consuming.” He also said he had “no experience in contract farming or credit/loan.” Sophorn did not respond to additional requests for comment.

Two years after the formal mediation process ended, the communities are now negotiating the family rubber farming contracts by themselves, directly with Socfin. Unlike during the five year mediation process, they have no legal representation or other civil society organizations supporting them.

The Mekong Region Land Governance project, an initiative run by two land rights NGOs, received more than $500,000 in funding from the Swiss, German and Luxembourg governments to implement the previous mediation between Socfin and the Bunong communities, according to a letter from a Luxembourg official, obtained by CamboJA. The United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights also provided funding, including for the communities to receive legal support and training.

Mekong Region Land Governance hired the Sydney-based consulting firm Australian Dispute Center to produce an evaluation report, published in April, to assess the 2016 to 2021 mediation process. The report concluded that mediation succeeded in “resolving all…categories of claims in the dispute” which included “contract negotiations for family rubber production.”

Kim said he and others were “afraid” to speak out about their unresolved debt with the company when the Australian Dispute Center team came in mid-2022, because they worried that doing so might lead them to not receive the benefits the company had promised, which had yet to be delivered at the time.

The Australian Dispute Center did not respond to requests for comment.

Antoine Deligne, deputy team lead for Mekong Region Land Governance, said he could not comment on the specific details of the 2016 to 2021 mediation’s outcome because the company and the communities had promised to keep the settlement agreements confidential. He acknowledged that it would be useful “to understand how the mediation is implemented in practice,” but said there were currently no plans to follow up on whether the company actually delivers on the promises it made as a result of the mediation.

Protecting Indigenous Land Rights?

The evaluation report commissioned by Mekong Region Land Governance said the mediation signaled to international investors in Cambodia that “indigenous land rights are being protected consistently with international instruments and norms”, citing the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

But Michael Nanz, co-president of the human rights group FIAN Switzerland that works closely with the Bunong Indigenous People Association, disagrees with this assessment.

“Indigenous land rights have been blatantly violated, not protected!” Nanz said in an emailed statement. “And UNDRIP is not about rights in mediation after consolidated land grabs, but about rights prior to land grabs.”

Among many provisions, UNDRIP mandates that “indigenous peoples shall not be forcibly removed from their lands or territories.”

Nanz argued that indigenous rights should be “protected and enforced” rather than “the object of negotiations.” He questioned whether donors such as the Switzerland, Germany and Luxembourg governments could support the mediation’s outcome when it “confirms these concessions and the eviction of the Bunong from their territory.”

A spokesperson for the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC), which provided Swiss government funding for the mediation process, said in email response on behalf of all government donors: “As the donors (Switzerland, Germany, Luxemburg) [sic] were not involved in the mediation process, SDC cannot comment…” The spokesperson added that donors deferred to the evaluation report.

The evaluation report touted the UN’s support for the mediation, stating that the OHCHR had a “balcony view of the mediation process…to vouch for its fairness” and was “wholly supportive.” The report noted the OHCHR provided “gap funding” and paid for the community’s legal support during the mediation.

Socfin said it “communicates transparently” with the OHCHR Cambodia office to “ensure that [Socfin’s] activities fully comply with applicable standards, including the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People.”

The OHCHR’s Cambodia public information officer Hammad Ahmad stated via email that only representatives of the OHCHR could make public statements about the OHCHR’s views. He added: “OHCHR will continue its activities in accordance with its mandate and maintain its close collaboration with relevant government institutions to ensure that Cambodia complies with its international human rights obligations.”

Pu Lu farmer Nam, like some Bunong residents of Bousra commune, affirmed the value of receiving a sense of closure from years of conflict but lamented that the community still lacks the ability to gain full rights over their land.

“We have lived here traditionally, we never paid rent,” said Na. “And we haven’t received full justice.”