NGOs and indigenous communities shared elaborate feedback with the Ministry of Land Management, Urban Planning and Construction (MLMUPC) on the new draft land law to ensure sustainable social development and ease people’s troubles.

The NGO Forum on Cambodia organized a workshop in February 2024 which saw over 100 participants from 90 institutions sharing views and commenting on the draft law, which was in line with a request for input by the ministry.

Nearly 30 proposals were made on the draft law, namely issues involving land acquisition, consultation with affected communities with regards to economic land concessions and replacement lands.

NGO Forum executive director Soeung Saroeun said the workshop also discussed collective land and state land, particularly compensation to people affected by various developments, which have caused problems for them in the past.

Participants also learnt in detail about the draft law, the process of drafting and approving draft laws, and collection of input from NGOs and communities, who are directly connected to land issues and the impacts of developments, he added.

A follow-up workshop on the draft law was organized by the MLMUPC on March 1 in response to queries and input by indigenous people on issues relating to them.

Mai Men, a representative of the Phnom Dang Santouch forest community, said the burial ground and spirit forests, which are sacred to them, had been indigenous places of worship for a long time.

He stressed that his indigenous Sui community cannot afford to lose their customs and tradition, even when the country was at war, as their ancestral beliefs must continue.

“If the state no longer does it [identify burial grounds and forest lands as indigenous lands], it is akin to annihilating indigenous cultures or removing indigenous people,” he asserted.

Men urged the government to provide details before granting land concessions to any individual, particularly consult with residents who are living in the affected area.

He said it allows indigenous people to bring the issue to the leadership in time as they are alerted and made aware of the impact the land concessions might have on them.

“If there is a land concession offered to any person, please provide a report and information, and consult with indigenous people. If there is advance notice, we can easily prevent it.

“If they [government] do something and we don’t prevent it, in future, there won’t be a place like this. It’s a risk to my people. So, find a solution to prevent it, for instance by talking to the leadership,” Men urged.

Over at Samrong Tbong in Phnom Penh’s Prek Pnov district, where authorities claim that the community has been living illegally on the banks of the lake and are currently facing forced evictions, calls have been made to settle the land issue.

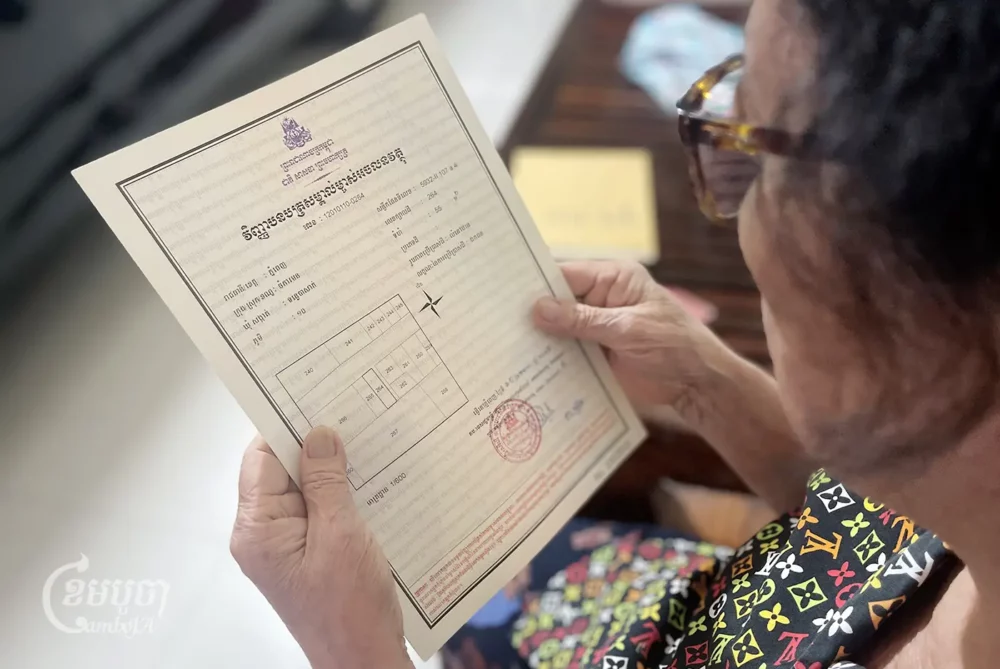

A resident there, Soeun Sreysoth, has asked the cadastral commission to resolve their land titles as they have been living there for decades. She alleged that the Prek Pnov district authority’s solution “nowadays is by way of coercion and pressure on the people”, which is not right.

“I would like to have a cadastral commission to resolve land disputes better than the district authority, which came to settle the issue with us because he [the district authority] is in charge of it. But, I do not know if [the authority] is biased for their own benefit or for the benefit of the individual or company,” she added.

Similarly, in Champei commune, Takeo province, where two hectares of farmland are affected by the new international airport project, resident Ith Pech has asked for higher compensation from the authorities, which is currently only $1 per square meter.

“[I want] to use this money to pay my bank loan, [but] they are only offering $1 per square meter. [I] want $3 or $2.”

Cambodia Center for Human Rights project coordinator Vann Sophath hopes that the new land law will protect the interests of the people, having observed numerous land acquisitions by the authorities where proper compensation was not offered despite possession of land titles.

“Whether it’s the new land law or old land law, please put the citizens’ interest first. It’s because they have land titles [but continue to] be subjected to land acquisitions with no proper compensation or that the replacement land is far away from their present location [the development site],” he said.

Speaking at the workshop, secretary of state of MLMUPC Theng Chan Sangvar acknowledged that the current land law does not adequately address the current social situation. Hence, the creation of a new land law, which is in the process of gathering feedback from stakeholders.

In response to the evolution of society, Chan Sangvar said the new draft land law details the procedures for the performance of officials, as well as the addition of new rules and regulations.

In early February, Land Minister Say Sam Al, who headed the meeting of the cadastral commission and the national authority for land dispute resolution said Cambodia will continue to carry out land reforms to create a conflict-free environment, manage and develop the land sector properly and effectively.

Preliminary input from civil society organizations on the new draft land law submitted to the ministry on February 16, requested the addition of the principle “conservation of the culture area and indigenous peoples heritage and respect human rights and indigenous peoples” to Article 5.

The input, viewed by CamboJA, also called on the government to clarify Article 25, where the immovable property of state property which may be the subject of a lease, should limit the specific size of private ownership to leave opportunities for the public to use it publicly. They cited Phnom Tamao and Phnom Bokor as examples.

As for Articles 37 and 38, they suggested that the draft law include the definition of indigenous peoples which is provided in the current land law. The new law also does not specify burial grounds and spirit forest lands belonging to indigenous people.

For Articles 59 to 73, they request the authorities to consult with citizens and obtain their views before granting economic and social land concessions. The decision to grant economic land concessions should also be discussed and voted by the national assembly.

The granting of economic land concessions at the border shall not be granted to the citizens of neighboring countries and should not exceed 30 years, the NGOs said.

As for Articles 106 and 107, the NGOs proposed the establishment of a cadastral commission to resolve land disputes if there is no title.

Assuming citizens are affected by the development, NGOs and land communities proposed that the state should provide fair and just compensation.

To achieve satisfactory results, the state should establish an independent commission consisting of stakeholders, from the state as well as representatives from national or international organizations, to engage in a transparent evaluation about compensation.

If replacement homes cannot be developed on site or resolved by other policies, the compensation mechanism should not be limited to monetary compensation, they said. Instead, affected residents may be relocated to an area with existing infrastructure and no more than 5km from their old location (affected area).

The state should establish a mechanism to provide compensation with a common standard nationwide, whether it is a public or private development, by studying good solutions or open to public consultation.

Responding to the proposals, Chan Sangvar, who is also MLMUPC’s legal working group chairman, said the new draft law has included “right of pre-emption”, which allows authorities to purchase land from people at a reasonable price and requires them to seek their permission.

He pointed out that this right contradicts the expropriation law, which forces people to sell land, adding that the new land law can benefit everyone.

“We welcome further questions, comments, participation and hope that we will get [to see] the final draft before it is submitted to the government,” he said.

The draft covers “all angles” and considers every stakeholder’s views so that it is balanced and preserves people’s rights while making sure development happens at the same time to ensure economic growth, Chan Sangvar added.

Land issues are prevalent in Cambodia, where some cases have prolonged for years causing families to fall into poverty or migrate while children drop out of school.

Land disputes have morphed now, with people having to pay off their mortgage but not receiving land titles, while others have not been able to pay their mortgage, only to have their land repossessed by creditors.

During the two years of the pandemic, thousands of people had their right to land and home violated, while many land activists were arrested and imprisoned for defending the encroachment of land by rich and powerful individuals.

Last week, the Tbong Khmum Provincial Court of Appeal sentenced four residents to two years in prison over a long-running land dispute with Chinese company Harmony Win Investment.

Additionally, at the end of 2023, over 50 people representing 300 families protested in front of Kampong Thom Provincial Hall to demand the release of a villager and allow them to travel on the road they always used to access their farmland.

Some time back, Kampong Thom Provincial Court sentenced seven indigenous Kuay people to one month in prison for “malicious denunciation” in connection with a land dispute.

Meanwhile, imprisoned Yoeng Mom, the daughter of Yoem Yan, who is the deputy director of Phnom Tnaot community forest land, hopes that new land law will protect the community and prevent abuse by the rich and powerful.

“Because the land law is a real law,” said Mom, whose her father is in jail for a land dispute case.

Minister Samal claims that Cambodia will complete land registrations before 2029, which will mark the 40th anniversary of the issuance of land titles to citizens.

To date, MLMUPC has issued about five million land titles to people, while another two million are being issued to the people daily. The remaining five million plots of land need to be measured and registered.