Beneath the waters of the Tonle Sap lies a little girl. Her name was Dang Thy, and even as she was bleeding to death from the bullet in her waist, she asked about the health of her mother, who was also dying from gunshot wounds following an attack by Khmer Rouge militants in 1998.

The graves of mother and daughter straddle Kampong Thom and Kampong Chhnang provinces, along a stretch of the Tonle Sap lake. The high waters in the past few years have enveloped the tombs, originally mounds of dirt secured by wooden planks. But they remain there, under the surface, and on every full moon night Dang Thy’s father Dang Ying Yu leaves an offering for her and her mother in the shrine at the back of his home. Once or twice a year, he takes his fishing boat to visit their resting place.

One day, in August this year, Yu sat alone in his home with an IV dripping yellow liquid into his forearm to treat a stomach ailment. He looked out past the canal in front of him, beyond the dilapidated houses of his village, returning to the waters of the Tonle Sap.

“Our hometown is here, so where else should I go?” Yu asks. “Our ancestors were all born here, so they do not want to go anywhere besides here. We are also scared, but we are willing to continue living here.”

As one of hundreds of ethnic Vietnamese living for three generations or more in Chhnok Trou village, Yu survived the Khmer Rouge regime and the decades of conflict that followed. Khmer Rouge guerillas mounted multiple attacks in the area, often targeting ethnic Vietnamese villages throughout the 1990s.

Yu and his neighbors have never been recognized as Cambodian citizens, and they’ve endured extortion, evictions, discrimination and violence due to their identities as one of the country’s most marginalized ethnic minority groups.

In 2018, Chhnok Trou residents were forced from their floating village on the lake to a land-based relocation site. Since then, the government’s discriminatory policies have limited their economic opportunities and hundreds of families have left in search of better prospects, threatening to dissolve the community.

Those remaining in Chhnok Trou say they have chosen to stay despite the ceaseless oppression in no small part because it is their home, where memories and traditions tie them together and the bones of their ancestors lie in the village’s cemeteries, on land and sometimes beneath the lake itself.

Memories and graves

The attackers screamed “kill the yuon” — a derogatory term for Vietnamese — as they opened fire on the floating homes closest to the shore of the Tonle Sap. The massacre of 23 people was one of an untold number of organized attacks by the Khmer Rouge against ethnic Vietnamese throughout the 1990s before they disbanded at the end of 1998.

Thirty-three were killed in the now-tourist-friendly village of Chong Kneas in Siem Reap, 14 slaughtered in Taches village in Kampong Chhnang and nearly 130 ethnic Vietnamese murdered in targeted Khmer Rouge attacks between 1992 and 1993, during the United Nations Transitional Authority of Cambodia. In 1992, Khmer Rouge assailants abducted and presumably killed a group of Chhnok Trou fishers, and that same year “shot or clubbed to death” eight ethnic Vietnamese in the village, Amnesty International reported.

The vice president of the village’s Ethnic Vietnamese Association, Hak Yang Phoeuk, keeps a box with two blood-stained shirts in his home.

They belonged to his sister Mak Thy Mai, who was among those killed in the 1998 attack. Mai was buried alongside Dang Thy and her mother, but Phoeuk exhumed his sister 10 years ago and moved her to another ethnic Vietnamese cemetery in the provincial capital to be closer to other relatives’ tombs. The tide had worn away Mai’s grave when she was exhumed, but Phoeuk salvaged two planks from her coffin, which he keeps as rafters in his home.

“She was innocent. How come they killed my sister?” he asks, removing the shirts from the box, brushing off the dust and smoothing away the creases.

“I miss her immensely. I had only one sister, but she is gone. My affection for my sister, the feeling that she was always close, made me want to keep them as a souvenir, so that the next generation would know about her.”

Her son, who survived the attack, married earlier this year and photos from the wedding adorn the walls of Phoeuk’s home.

“There is a feeling that makes us not go far, even though we are separated. The graves of our ancestors, parents, siblings are all here, so we keep on living here at all costs,” Phoeuk says.

Down the road, in an overgrown plot of land surrounded by rice fields, many in the ethnic Vietnamese community have buried their relatives in an overcrowded cemetery filled with above-ground tombs — unlike the cremation practices of Khmer culture. Older generations had buried the dead in cemeteries on the outskirts of Khmer pagodas in the area, but these sites were prone to flooding.

Denied citizenship, ethnic Vietnamese are barred from owning property, but community leaders say the village was able to buy a 90 by 75 meter plot of land for a cemetery in 2003 for $900. Keeping the deceased close together is an important part of ancestor worship and filial piety, community members say.

Some have had to bury relatives elsewhere. Villagers say the man who sold them the plot of land insisted on making the tombs and forced the community to pay him exorbitant rates, even though many thought his craftsmanship shoddy. If they tried to build a tomb themselves on the land, they say the man would take a hammer and destroy it, leading some in the community to travel an hour away to bury relatives at another ethnic Vietnamese cemetery in the provincial capital.

When the man who sold them the land died, a Khmer villager claimed the land belonged to him and began selling chunks of the land to others, even though it had been in the community’s possession since 2003, according to Le Yang Kor, acting chairman of the Kampong Chhnang province’s Ethnic Vietnamese Association.

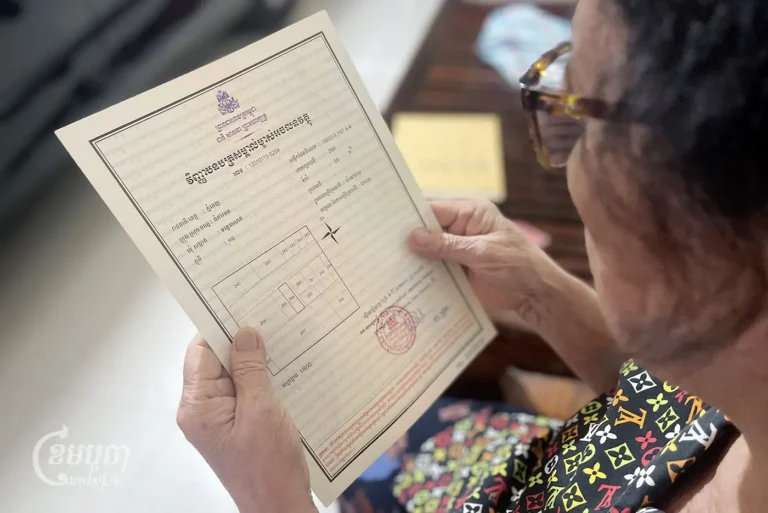

Frustrated, Kor says he retains the original letter of purchase for the plot of land. Though the community’s control over the cemetery remains tenuous, Kor notes that, after the tomb maker passed away several years ago, the man’s son took over and has treated the community better.

“It is important for us because our religion does not cremate like others,” Kor explains. “When our ancestors, parents, or siblings die, we have to bury them. And we felt better and happier after we secured a place to bury the graves of the communities.”

Returning to the water

There were once more than 800 ethnic Vietnamese families living in the Chhnok Trou floating village on the waters of the Tonle Sap, one of the only places ethnic Vietnamese communities can reside without recognized property rights.

Yet in 2018 the government ordered them and other communities in the area — around 10,000 ethnic Vietnamese people and nearly as many Khmer and Cham families — to move onto land.

Authorities claimed the mass evictions were a response to environmental pollution and overfishing in the lake.

Today, around 30 boats belonging to ethnic Vietnamese families bob along the inlet marking the site of the old Chhnok Trou floating village. Families still raise thousands of fish under these boats, and sell food, gasoline and mechanical services to each other and passing fishers.

Chhnok Trou’s Khmer commune chief Tang Kimsorn said that some families were allowed to do fish farming in the area but were “not allowed to build houses there.”

Military police prohibit anyone living on the water from using a structure with a roof, apparently under the logic that this constitutes a home and defies the 2018 eviction order. Every couple of months these officers require a $25 payout to not demolish the homes, a significant amount, several residents still living on the water say. Some residents have relied on detachable roofs for their homes to mitigate the periodic roof demolitions.

On one boat, Ming Yang Kuar smokes a pack of Hero cigarettes, dropping the ash into the water through the gaps in the raft’s floor. He rests from the sun in the shade of his sugar palm leaf roof with Vietnamese-branded rice tarp sacks woven in to block leaks.

“They forced us to live inland but we could not reuse anything from our old house there,” Kuar says. “They [authorities] allow us to have houses but no roofing, but how can we live in the blistering sun?”

Yang’s children kneel behind him in the corner of the home, watching videos on their phones, which Yang explains is how they learn instead of attending school these days.

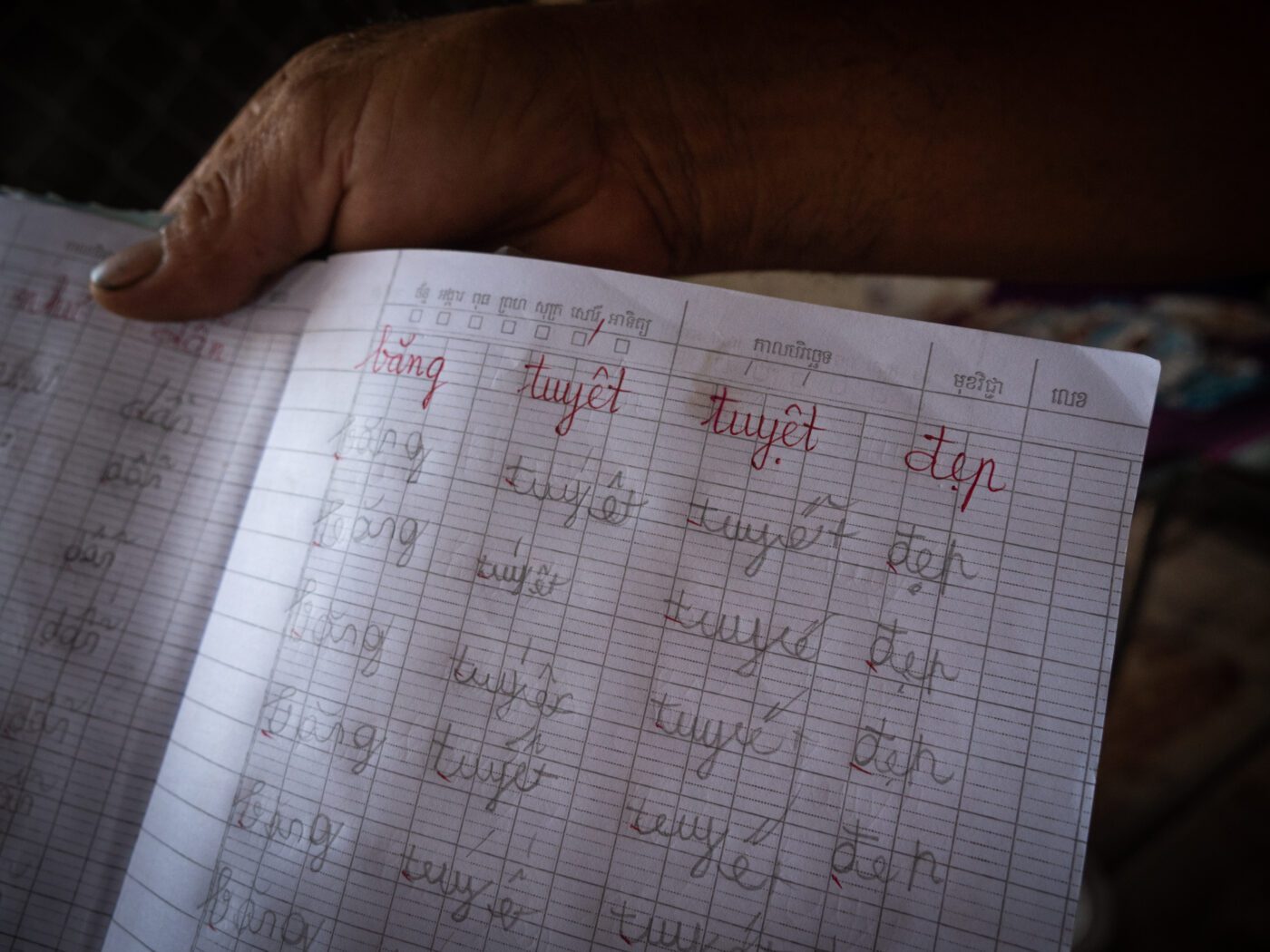

Most ethnic Vietnamese children in Chhnok Trou are not allowed to attend state public schools for lack of citizenship, so the community established their own informal Vietnamese language school. But for families like Yang’s on the water, bringing a child to and from the school seems too costly and difficult. Instead, if the children are lucky, their parents pay a 2,000 riel an hour fee for a tutor to come teach them each day.

Another elderly ethnic Vietnamese man, who requested anonymity because he is still living on the lake, stood neck deep in the shallow water beneath a large boat he and his daughter were repairing.

“I was born on a boat, there was no state health clinic,” he says. “I don’t even know how to drive a motorcycle or a bike, because I have always lived on a boat. If I could, I would work as a moto driver, but I am more comfortable on boats.”

Like many of his neighbors, he has been living in the area since before the Khmer Rouge arrived in the mid-1970s. He then fled to Vietnam but returned in the 1980s. During the mass exodus of ethnic Vietnamese communities from Cambodia, many documents and records of their citizenship or residence were lost or destroyed, leaving them to be treated as immigrants upon their return. In 2017, officials confiscated thousands of ethnic Vietnamese’ identification documents and began issuing permanent resident cards at a cost of about $60, which is too expensive for most villagers to afford.

Ethnic Vietnamese in Cambodia typically lack birth certificates, reportedly due to the prejudice and neglect of local officials. As of this year, ethnic Vietnamese babies can receive a birth certificate if they apply within one month of the baby’s birth, Phoeuk says.

The certificate is distinct from citizenship — which remains an unlikely prospect, Phoeuk notes. Cambodian officials have reportedly stated that ethnic Vietnamese could qualify for citizenship after seven years with permanent resident cards, but community leaders were not optimistic that authorities would follow through on this promise.

“Rumor is just rumor,” Kor says. “I have been living here since I was born. I would have gotten it [citizenship] by now.”

Instead of receiving citizenship, Kor, Phoeuk and their neighbors renew their permanent resident cards every two years, even though many were born in the country and see it as their home.

“We feel like Cambodian citizens,” Phoeuk says. “We have been living here for three generations.”

A barren relocation site

The land-based relocation site for Chhnok Trou residents is emptying of people.

Numerous houses lie abandoned, their roofs collapsed, floors sunken in and walls leaning precariously after the residents left to live in another floating village, moved to Vietnam, or migrated elsewhere for better work opportunities. The lack of property rights inhibits even those willing to remain at the site.

“I don’t have a land title,” says one middle-aged man, who requested anonymity and lives in a home with four family members. He explains that if he had legal ownership of his land, he would build a pond to breed fish, but feels it would not be a safe investment otherwise.

Every year, these residents must also renew their agreements with the commune, permitting them to live on the land at the relocation site.

“It appears like the government rents the land to us so we can live there temporarily,” the man says. “I do not know when we will be forced [to move] again. I cannot do anything on this land.”

During the 2018 relocation process, families were required to pay for the cost of moving and rebuilding new homes. The community has since been responsible for paying for their own water supply and has had to build bridges to cross the canal running through the village, though local authorities fund electricity for their homes.

Unlike the relocation site nearby where their Khmer neighbors were sent, which has a wide, smooth red dirt road, the relocation site given to the ethnic Vietnamese has a potholed and uneven dirt trail, hindering vendors as they push their carts down the bumpy path. Other relocation sites for ethnic Vietnamese in the province have also fared poorly, in areas vulnerable to severe flooding and without proper infrastructure.

“If we had a new road, a lot of people would come to live here, but if there is no road, they will not be here because they cannot find anything to earn,” Phoeuk says. “And as for the land, there is no ownership anymore. Some people do not dare [to live on the land] because they are afraid that one day they will have to go somewhere else.”

Around 50 families have since moved from the relocation site to another ethnic Vietnamese floating village called Phat Son Dai on the border of Kampong Thom province, a 15 minute boat ride across a narrow stretch of the lake.

Ly Yong Hou’s wife and five children live at the family’s home on land at the relocation site, but the 42-year-old Hou spends multiple weeks at a time in Phat Son Dai running a boat mechanic business on the water.

“The problem is about our livelihood. We are accustomed to living on water. If they evict us and require us to live inland, it is hard since we do not know what to do for business,” Hou says.

In July, the Cambodian government published a January sub-decree reclassifying 443 hectares of land in Kampong Chhnang’s Boribo district as a relocation site for families from Chhnok Trou and three other communes to move to, the database Kamnotra reported. Cambodian families — implying exclusion of the ethnic Vietnamese — can receive ownership of land at the relocation site, the decree states; all are prohibited from living on the water again.

Village leaders, Chhnok Trou commune officials and Boribo district authorities claimed they were unaware of the new sub-decree, which appeared to be reinforcing the 2018 relocation. But ethnic Vietnamese like Hou wonder when they might be expelled from their new homes on the water at the nearby Phat Son Dai floating village, or even moved from the inland Chhnok Trou relocation site.

“I have heard rumors that authorities plan to relocate more people. I am concerned about it, but what do I do since we live under their authority?” Hou says.

Honoring ancestors, together

Though the future of the Chhnok Trou community and other floating villages in the area remains uncertain, for now residents still come together to uphold long standing traditions.

Dozens of villagers gathered on August 30 at their stilted pagoda at the Chhnok Trou relocation site to give offerings for their deceased relatives. The event was part of the Ghost Festival, when village ghosts are said to wander the earth seeking food from their living relatives.

The ghosts’ presence is also believed to coincide with the arrival of rain, the monk leading the ceremonies explains.

“Big festivals are accompanied by good rains because people believe that ancestors feel fulfilled after their relatives’ offerings,” Phoeuk says.

Inside the pagoda, praying villagers bent their heads down, their hands pressed together, fingers pointing upwards and thumbs close to the chest. There are fewer people present than previous years, villagers say, but many of their former neighbors and relatives returned from Phnom Penh to participate.

“Those who have spiritual relatives who lived in Chhnok Trou always come to celebrate together,” says 65-year-old Wang Yang Sok, an ethnic Vietnamese villager. “This event demonstrates the tradition of ancestor worship that stretches back thousands of years.”

Outside, sacks of rice accumulated in a pile two meters high, and the community cooked vats of a mixed fruit dessert called keam. For some villagers, the festival provides a crucial source of welfare in the absence of family support along with the limited economic opportunities at the relocation site.

After receiving blessings and feasting on the dessert, community leaders like Phoeurk’s family distributed rice, noodles, canned fish and other gifts to the elderly and their less-well-off neighbors.

By afternoon, the gifts have been distributed, the food eaten and the prayers and worship complete. The villagers disperse and those who had traveled from Phnom Penh load up in a rickety cart drawn by a motorcycle, ready for the long ride back to the city.

After the ghosts have eaten their fill, the wind picks up, the clouds darken, and by the early evening, as the traditional wisdom anticipates, rain pours down on Chhnok Trou.