Cambodian observers say the government’s hesitancy to shut down parts of the economy even as Cambodia deals with its first community transmission cluster bares concerns over the health of an already-struggling economy.

Government and health officials are scrambling to contact-trace, test and isolate people who are part of a new cluster of 19 reported cases, as of Thursday morning. The cases are the first community transmission incident where health officials are not sure of its origins.

Last week, the government was quick to shut down schools, entertainment facilities, and ask anyone in direct or indirect contact to stay home for 14 days. But, as with previous outbreaks, the government has shown no inclination to temporarily shutter bustling markets, construction sites, restaurants and bars, crowded factories and other offices.

Hong Vannak, a business researcher at the Royal Academy of Cambodia, said allowing these businesses to continue was indicative of the government’s concerns over a potential impact on the economy.

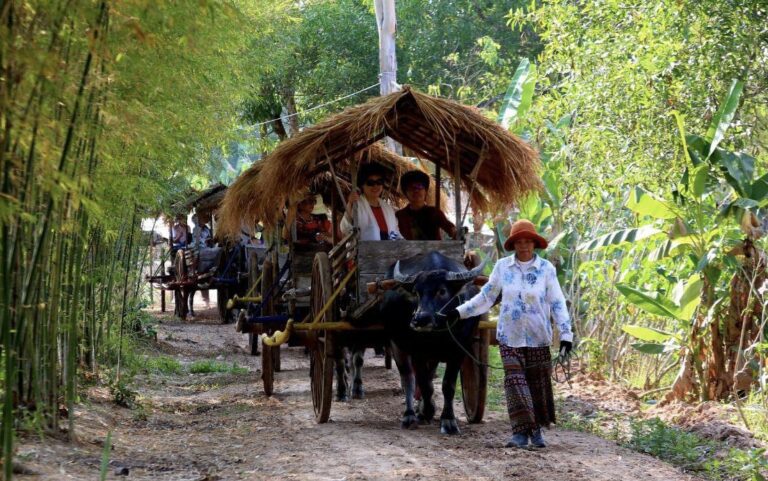

The government was reluctant to allow these businesses to meet the same fate as that of the tourism sector, he said, which has been the worst affected on account of global travel coming to a standstill.

“I think business is more important. As we already know Cambodia’s economy is still muted and we cannot put long restrictions” he said.

He added that a lockdown or temporary shutdown of revenue-generating sectors would also hurt the prospects of an investment-reliant economy.

“If reflecting on the economy, long restrictions will interrupt business activity that will hurt people’s incomes, who need it to pay back loans,” he said.

The Cambodian economy, which is export- and investment-dependent, has taken a hit during the COVID-19 pandemic, much the global markets. The World Bank expects the economy to contract around 2 percent and the Asian Development Bank has a bleaker estimate of negative 4 percent GDP growth for the year. Both development banks expect the economy to rebound next year.

The garment sector has been severely affected, with Labor Ministry figures showing 489 factories were suspended and 83 had officially ceased operations as of June this year.

Cambodia’s annual $7 billion garment and textile sector is also dealing with the partial loss of a preferential zero-tax trade deal provided by the European Union.

Exports in the garment sector dropped more than 5 percent to around $3.78 billion in the first half of the year, according to a report from the Ministry of Labor.

Ath Thon, president of the Cambodian Labor Confederation, said that health guidelines and measures during the recent outbreaks were not being implemented across the board, putting workers at serious risk.

“These measures are too limited,” he said. “Workplaces such as garment factories, which is the most susceptible place for virus transmission, are not included, there is no social distancing, and workers are loaded together in crowded trucks.” He admitted that workers did want to continue working, given the lack of employment in the rest of the economy, but that an outbreak among workers would disproportionately affect this vulnerable community.

“If there is any transmission among poor communities, it will be a serious issue and I think appropriate and strict [health] measures should be applied at all places to prevent [risk to] the industry as a whole,” he said.

Sean Sreysar is one of the lucky workers whose factory is still open. She represents the dual, and often conflicting, concerns of factory workers – they want to keep working but know it comes with a potentially heavy health risk.

When Cambodia first saw its COVID-19 tally rise steeply in March and April, Sreysar wanted her factory to close because she was worried the virus would spread fast. But, after a one-month suspension in May, Sreysar returned to work to find temperature checks, requirements for face masks and some social distancing.

Relieved to get back to work, Sreysar is still nervous about catching the virus in the factory or on her way to the factory in overcrowded flatbed trucks.

“For me, when I arrive home from work I need to take a bath before touching my children or cooking food,” she said.

Health Ministry Secretary of State Or Vandine said the government had put in place certain restrictions to see if it could stem the spread of the disease. She said these could be expanded if needed.

“We don’t know yet [what measures] will be needed in the future but we need to ensure that the situation is controlled,” she said.