Child labor and debt bondage continue in Cambodia’s brick factories, according to a report published Monday by the human rights group Licadho. The organization also found garment waste from international brands such as Reebok, Old Navy and Adidas fueling kilns in brick factories.

“The Cambodian government allows debt bondage and child labour to continue in plain sight,” said Pilorge Naly, LICADHO’s Outreach Director, in a statement. “For decades, Cambodia’s cities and developments have been built upon the exploitation of brick factory workers. It is past time to end modern slavery and child labour in Cambodia’s brick factories.”

Licadho researchers witnessed children cutting and feeding clay into manual brick-making machines, which can tear off workers’ limbs. The team saw children slicing clay using wire tools, moving bricks off of conveyor belts, pushing carts carrying bricks, and loading bricks onto trucks.

The findings are a result of visits to 21 brick factories in Kandal province and Phnom Penh this year as well as interviews with current and former workers.

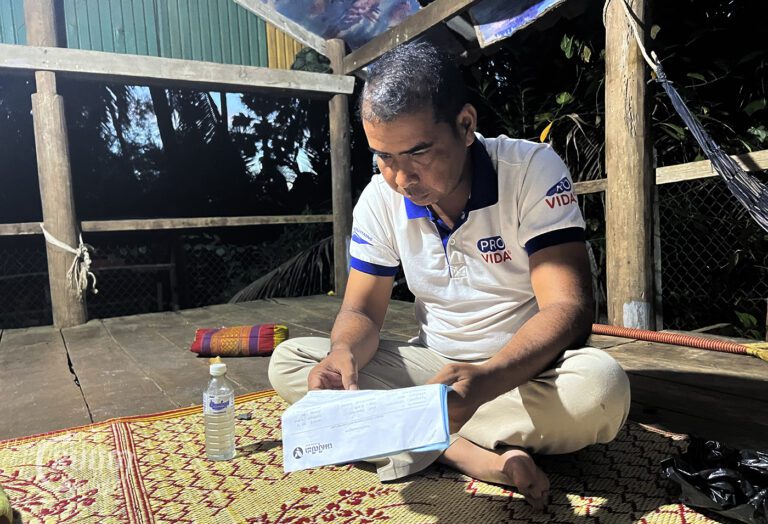

Debt bondage, where workers are forced to work for an employer in order to pay off loans, remains common in the industry, according to the report. Laborers earning low wages often must live and work at the factory until they have repaid their loans, with some factory owners keeping the identification documents of their workers. Workers reported to Licadho that police or other local authorities have been present when loans are signed.

Debt bondage can be an element of forced labor or human trafficking, according to the International Labor Organization and the UN. Confiscating documents is also an indicator of trafficking.

Covid-19 slowed construction in Cambodia, which caused a decline in demand for bricks and the shuttering of some brick factories. The factories still operating have little business, and Licadho staff reported that factory owners have responded in different ways to the downturn. Owners have transferred workers to other types of labor, required workers to wait at stalled factories with no income, allowed workers to leave temporarily, or in some cases canceled workers’ debts.

Licadho said it found no systemic improvements in the industry since its 2016 report. Media reports and academic research in the last five years have documented debt bondage and child labor in Cambodia’s brick factories, including the story of a 10-year-old who lost her arm in a brick machine.

Labour Ministry spokesperson Kata Orn told CamboJA that labor inspectors for the ministry have patrolled factories a total of 353 times since 2021 and have found that “there is no use of child labor and debt bondage.”

He said the ministry has worked to eliminate child labor and will investigate any suspected cases. Violations could result in fines, business closure or criminal charges, he said.

“The government’s charade of inspecting brick factories, only to deny the existence of any problems, is a shameful effort to obscure the truth,” Licadho’s Naly said in a statement.

Government spokesperson Pen Bona told CamboJA that the government asks that Cambodia’s civil society groups remain unbiased and accept the “hard work” of the government.

“The government has done a lot of work to prevent these problems [child labor and debt bondage] and received a lot of good results,” he said. “However, there are still a few cases [of child labor].”

He said there is “not much” child labor in the country now. The government has worked to educate Cambodian parents not to have their children work in ways that are against the law, but some still ask their children to work as “it is customary,” he said.

Chou Bun Eng, Vice Chairperson of the National Committee for Counter Trafficking (NCCT), acknowledged that debt bondage is a form of human trafficking, but said that cases need to be evaluated by experts according to identification principles outlined by the NCCT.

“Publishing without agreement or a basis for identification is not the thing to do,” she told a CamboJA reporter on the phone in response to Licadho’s report, adding that the NCCT is “vulnerable to the publication [of reports] without proper identification.”

In September Bun Eng told CamboJA it “was difficult to accept” a finding in a UN report that at least 100,000 people have been forced to carry out online scams in Cambodia, claiming that the report included the figure without evidence.

“If it is the case that children work as housemaids, at brick factories, or at a restaurant or guesthouse, it is recruitment without the law’s permission,” said Em Chan Makara, spokesperson for the Ministry of Social Affairs, Veterans and Youth Rehabilitation. “We do not encourage and there is no law that allows child labor via these means to solve debts or family livelihoods.”

He acknowledged that child labor has occurred at brick factories for “a long time.” The ministry will use Licadho’s report to help solve the issue of child labor and will send it to the Cambodia National Council for Children to respond further, he said.

He did not provide a response to CamboJA’s question asking if the ministry had issued any exemptions allowing children aged 16 and older to work at brick factories in the country, which the ministry is able to do under Cambodian law.

Cambodian National Police spokesperson Chhay Kim Khoeun did not respond to a request for comment.

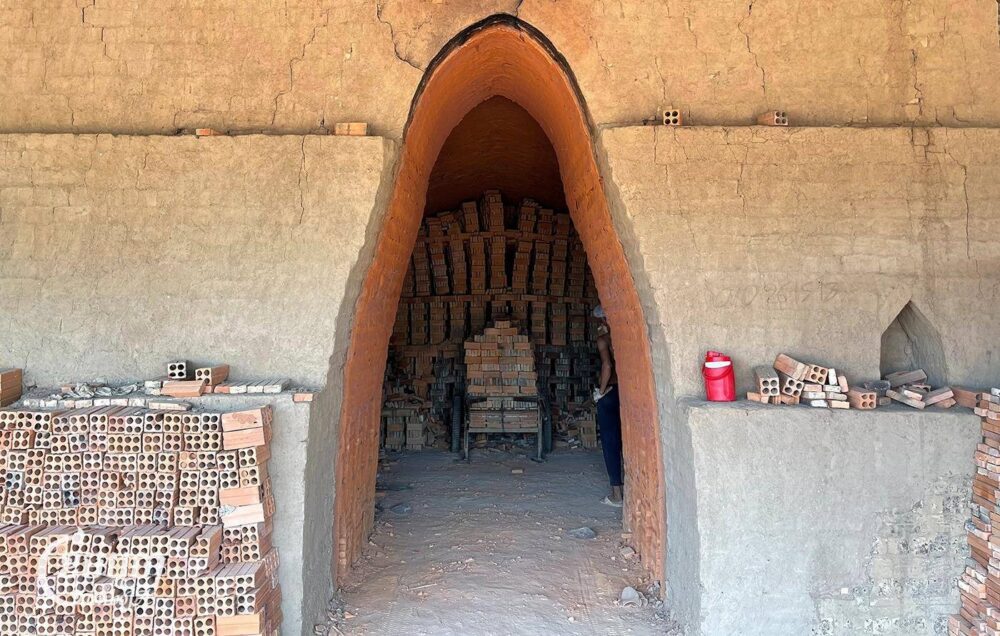

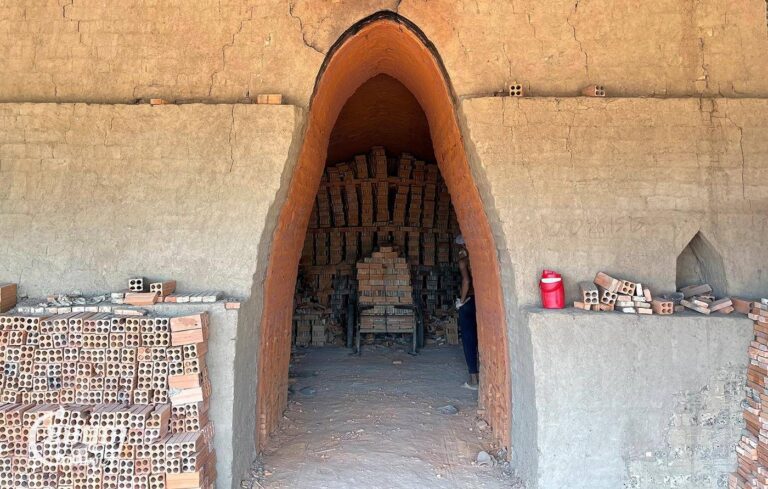

Garment waste from international brands fuels brick kilns

Tags bearing Walmart, Under Armour and Gap logos stuck out of piles of clothes at brick factories this year, as documented in photos taken by Licadho staff. The NGO’s team found garment waste marked with 19 international brands at seven brick factories.

Scraps of fabric, rubber and plastic discarded by the garment industry are mixed with wood to fuel brick kilns, which is damaging to the environment and health of local communities. Workers reported headaches and problems with breathing caused by the burning of garment waste.

Cambodian law requires that garment waste, considered hazardous, be transported and disposed of by companies with Environment Ministry permits. Phay Bunchhoeun, spokesperson for the Environment Ministry, did not respond to a request for comment.

Of the 19 brands that Licadho reached out to on October 24, Adidas and Lululemon told the organization that they would investigate the findings.

Adidas said in an email to CamboJA that if its investigation finds that the company’s supplier partners are involved in diverting waste to brick kilns, “it would be in breach of our policies and lead to enforcement action.”

The German retailer Lidl, which owns the clothing brand Lupilu, stated in an email to CamboJA that the company had “initiated further investigations” into what Licadho had reported.

“Investigations must be carried out impartially and thus take some time to identify violations and implement effective measures. Due to the ongoing procedure, we cannot provide you with any further information,” a Lidl spokesperson said in an email.

In an email to CamboJA, a communications representative of Otto (GmbH & Co KG), which owns the American clothing company Venus Fashion, wrote: “We appreciate the diligence of those who bring such concerns to our attention and are committed to addressing these allegations transparently and taking appropriate measures.”

“…Sweaty Betty’s suppliers around the world commit to our stringent Environmental Code of Conduct,” the British activewear company Sweaty Betty, owned by Wolverine World Wide, Inc., said in an email to CamboJA News. “We continue to work closely with our supply chain partners to ensure full compliance.”

As of 3 p.m. ICT on Monday, the company had not responded to Licadho, according to the NGO.

“We closely monitor our suppliers through third-party verified assessments and follow-up visits by own local staff. If we receive indications of irregularities, we investigate them immediately,” the clothing company C&A, owned by COFRA Holding AG, wrote to CamboJA in an email.

As of 3 p.m. ICT on Monday, the company had not responded to Licadho, according to the NGO.

“We are unable to comment on the origin of the packaging shown in the Licadho document, but we can demonstrate that the factory used for the production in 2021 had the necessary contracts in place to ensure the secure disposal of waste in accordance with local legislation,” said Neel Prasad, Vice President Global Sourcing & Supply Chain at the Canadian hat retailer Tilley, in an email to CamboJA.

CamboJA did not received responses to requests for comment from Walmart, Disney, Lululemon, Under Armour, Gap, Authentic Brands Group (owner of Reebok), Associated British Foods plc (owner of the clothing brand Primark), LPP (owner of clothing brands Cropp and Sinsay), Karbon or Kiabi.