A report by NGO Sahmakum Teang Tnaut Organization (STT) revealed that people who are forcibly evicted from their homes without proper resettlement are burdened with debt, have low access to food, while children experience disruptive education and are subject to child labor. Experts warned that this would have detrimental effects on the community’s economic and human development.

Between May and July last year, the organization conducted a three-month research project, which highlighted the critical situation of forced evictions in Cambodia. The report, “Eviction, Compensation, and Debt 2023” outlined a “gross disregard” for national laws, international human rights law, and UN recommendations. Twelve areas in Takeo and Kandal provinces, and Phnom Penh municipality, where residents were allegedly evicted during Covid-19 between 2019 and 2022, were studied.

A majority of the residents in those areas had been there since the 1980s, but many were forced to leave the place because of province-city development projects. For instance, the new airport project, Phnom Penh-Sihanoukville Expressway, those residing on privately-owned land bought by developers from the state and the capital city’s 30-meter road expansion are among the reasons given by the government for the evictions.

According to the report, each eviction occurred differently, resulting in unique outcomes, in terms of negotiation processes and compensation packages, which meant that evictions failed to follow a prescribed process.

The NGO also discovered that most of the forced evictions impacted the lives and emotions of people, who were already suffering from economic hardship and poverty. Because of the inconsistent negotiations and compensation processes, evicted households are psychologically affected in addition to losing their homes, jobs, income, education, and access to public services.

Speaking to CamboJA, Kong Srey, 65, explained that her decision to accept the compensation and relocate from Samrong Tbong village in Phnom Penh’s Prek Pnov district, was made due to several concerns. This includes the fear that she and her neighbors may undergo a similar fate as other communities affected by Boeng Kak development.

“We were afraid they would clear us [out] like [they did] in Boeng Kak and [the land] would be left empty, so I came here. But when I came here, life was even harder.”

Since her relocation to Toul village in Pun Sang commune, about 15 kilometers from her previous home, in 2022 with 13 other families, Srey said it has been extremely difficult to earn a living because there was nothing to do there. Most of the people had no choice but to find work in construction sites and contend with low salaries. A few people left to look for jobs in the province while others closed their homes and returned to sell fish at their old stalls near the lake, renting houses closeby.

“It was very difficult after we came to live here. If we were there [Boeng Tamok], we would’ve just fished. Unfortunately, we’ve found nothing [jobs] here but construction work,” she said, alleging that the construction supervisor cheated them and failed to pay their wages.

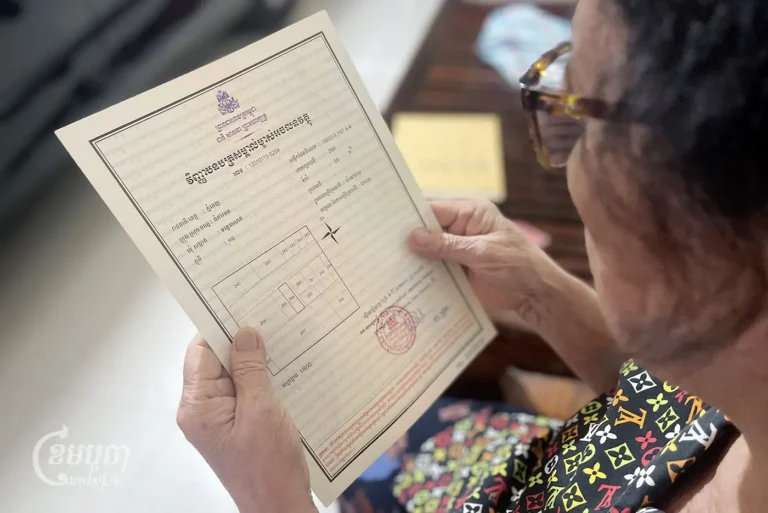

As if that was not bad enough, Srey rued that she had a debt of over two million riel, which she borrowed to pay people to move her things from the old place as the government’s $500 compensation was not enough. So far, all 13 families have yet to receive their land titles because the documents are still being processed.

Nop Sinan, 52, who was also evicted from the Boeng Tamok community to Toul village, which is 15 kilometers away, used to earn between 80,000 and 100,000 riel (about 20$ 25$) from selling fish that was caught in the lake. After she relocated, she lost most of her income. The 25,000 riel (about 6.25$) she earns as a construction worker a day is insufficient to regularly service her four million riel debt.

Tears in her eyes, Sinan said she was worried about losing her current house because of her debt for which she has to pay $200 every month. She added that there are only two people in her family who can work as she has a disabled child living at home.

“It is possible [that I could lose this land], as I am not able to pay [my loan], not even the interest fee.”

Nuon La, 34, a fishmonger, who used to live near Deum Kor Market for over 10 years, was evicted by the authorities in 2020 and relocated to North Vihear Sour Village, in Kandal province’s Khsach Kandal district. Her income has since dropped and is not able sustain a proper livelihood apart from selling a small amount of fish.

She too possessed a private loan of more than two million riel (about 500$) debt and is struggling to pay it back because a few months after she took out the loan to invest in a stall near the Deum Kor market, she was evicted. The loan was not used for any business.

“I’m not sure how much I pay a month or a week,” she said, adding that she would sell whatever amount of fish she catches, which was not much, to raise the money. “I dare not eat the fish because I have to pay back [the loan], and save some [money] to buy rice and pay my children’s school fees.”

Commenting on the issue, Soeung Saran, executive director of STT and Yang Kim Eng, president of the People’s Center for Development and Peace urged the government to provide adequate housing and help defer the repayment of debts by the people before relocating them.

STT said the government should take into account the people’s circumstances before evicting them, and provide more public infrastructure such as schools, hospitals, electricity, and water for their livelihood. On delaying debts, Saran said the government ought to work with creditors to delay people’s debt repayments.

Government spokesperson Pen Bona declined to comment, stating that he has yet to see the report.