In a move decried by rights groups and local residents, this month officials in northern Phnom Penh are moving ahead with the forcible eviction of small communities living in a lake area being filled for new development.

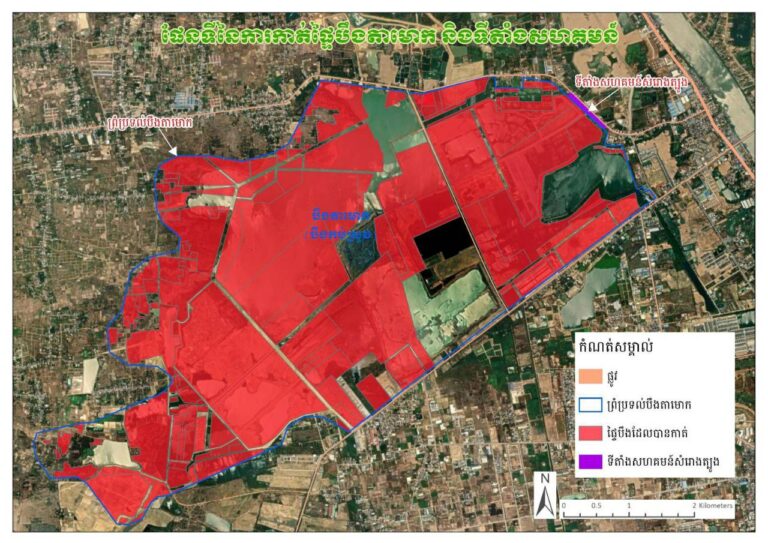

Authorities say the settlements around Boeung Chhouk lake in Russei Keo district are built on state land, meaning the residents there are not entitled to any set compensation for lost property. Though some officials have negotiated settlements with affected villagers, residents told CamboJA they haven’t yet received anything even as house demolitions have already begun. Amidst the ongoing COVID-19 crisis, which has already hurt the livelihoods of low-income residents of the lake area, evictees say they have nowhere else to go.

Heang Sopheak, a construction worker, said his small wooden house was demolished by Russei Keo district authorities last Friday without prior notice and while he was away from the village.

“My children called me, saying the house was demolished. I quickly returned home, and it was half moved,” he said. “I and the other villagers stopped them, and they left. Now I do not work, because I am busy repairing the house.”

Sopheak claims to have been living here since 2008. He says his family and 22 other households have been living in Spean Leu village, of the Boeung Chhouk community in the Kilometer 6 commune for years by building small wooden houses alongside the lake.

In the early years, Sopheak says, the lake had been a large area full of lotuses. Now, he says it is being filled for public infrastructure development and private projects.

“When I first came to live here more than ten years ago, there was no ban from the local authorities because it was a lake. Everyone lives on state land, we just want a place to live decently,” he said. “Since I have lived here, the authorities never come to meet people, they come only during the election.”

It’s unclear if or how the residents will be compensated for leaving the site.

“They require us to move, or the houses will be demolished without responsibility for any damages,” he said. “At first, they said they would offer each family $500 for those who voluntarily move but a day later, they said each family would receive only $125.”

He said people have refused the offer and asked district authorities to allocate a small plot of land elsewhere nearby in the district for them.

Other residents told CamboJA they’d been making their home at the lake for even longer still.

Cheng Saron, 47, and a widow with four children, said she has been living here since 1994.

Saron said her family has for years depended on picking lotus in the lake to make its daily living.

“I could earn about $20 a week from selling lotus, but now markets and the pagoda are closed [due to COVID-19] so I cannot sell it like before,” she said. Without income, Saron said she has nowhere to go now that authorities have asked her to leave the lake.

“If they require us to leave without any compensation or exchange other places for us, I will have no place to go, I really don’t know what to do now,” she said. “I am really worried about my children’s future. [They] have already dropped out of school and they will be homeless.”

Spean Leu village is not the only site on the lake where families are being forcibly evicted. Another 20 families in Boeung Chhouk village, about one kilometer away, also face the same fate.

According to urban rights group Sahmakum Teang Tnaut (STT), as of August 4, 11 of the 20 houses in Boeung Chhouk village have been demolished without compensation. STT reported local authorities had previously invited all 20 households for a meeting on August 28, 2020, to discuss compensation in the form of plots of land to be provided to the affected community members. More recently, the organization reported, authorities promised each of the households approximately $125, which locals said is money they have yet to receive.

The villagers there have reportedly asked authorities to provide affected families with plots of land along the O’ Veng canal in Russei Keo, where they claim other displaced people have been settled.

Phnom Penh deputy Governor Keut Chhe did not comment, referring questions to district authorities. Neither Russei Keo district Governor Chea Pisey nor his deputy Su Sokun commented on the evictions when asked.

Am Sam Ath, deputy director of rights group Licadho, said development should occur in a transparent manner and with justice for all. He also said forced evictions could pose a risk of COVID-19 infection as people will have no proper place to live or access to hygiene.

“Any developments that affect people, [they] need to be fairly solved and acceptable,” he said. “If those could not benefit directly from the development, we need to ensure that they remain living decently. A development that makes them lose homes, lose jobs, is a development without sustainability and transparency.”

Sam Ath said the capital’s informal settlements may be on state land but have previously been allowed to exist, meaning that officials share some of the responsibility for their situation.

“I don’t think authorities should only blame people because all settlements are known by local authorities — the authorities should ban it from the beginning,” he said. “Otherwise, citizens may claim their legal benefits for living a long time on the land and authorities could not avoid the responsibilities.”

“Authorities should not accuse them of living anarchically on state land when it comes to potential development areas.”

Plong Hoeun, a 44-year-old tuk tuk driver who made his home along the lake and is now facing eviction, said he’s still insisting on another place to build a small house for his nine family members.

“I used to earn $20, but now I earn only $5 and some days I cannot earn even a dollar. I’m very worried and don’t know where to go,” he said. “None of the villagers here received any government subsidies even during COVID-19 and the authorities never visited the people here.”

(Additional reporting by Chea Sokny)