With the main opposition CNRP banned and one of its former leaders, Kem Sokha, facing trial on treason charges in January, observers say next year’s commune elections will likely be dominated by Prime Minister Hun Sen’s long-ruling CPP.

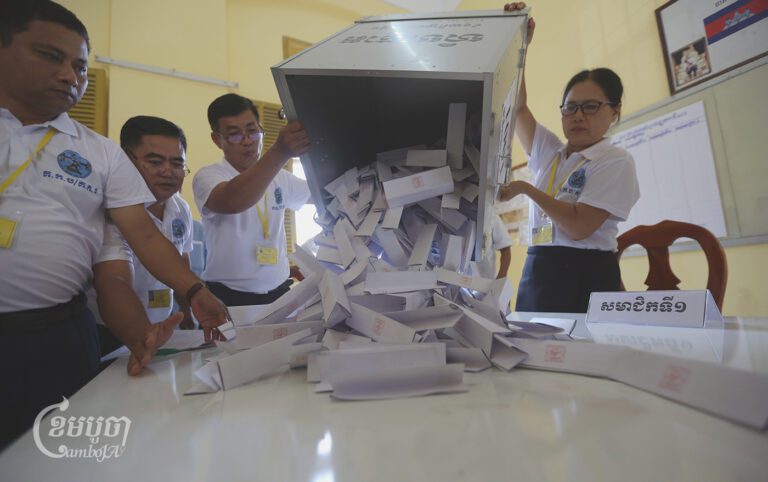

Cambodians go to the polls on June 5th to vote for their commune chiefs and council members in 1,652 communes in 25 provinces — but smaller splinter parties are desperately short of funds and resources.

In 2013, the opposition CNRP pushed the ruling party to near defeat in national elections, and again in commune elections in 2017 the CNRP did well — with some 5,000 opposition councillors winning seats compared to just over 6,000 CPP councillors.

What followed signalled the effective end of the country’s only credible opposition. CNRP leader Kem Sokha was arrested on treason charges widely believed to have been politically motivated and the party was controversially dissolved by Supreme Court order. Following the party’s dissolution, 118 opposition officials were banned from politics for five years.

In the subsequent 2018 national election, the CPP swept all 125 seats.

The Cambodian government has since permitted the “rehabilitation” of some two dozen banned opposition members, who have had their political rights restored. Several of them, from both Sokha and Sam Rainsy’s factions, have formed new parties including Khmer Will, Cambodia Reform, Khmer Conservative, Cambodia National Love[1] and Cambodia National Heart.

Opposition Hopefuls

The newest, the Kampuchea Niyum Party, was started in July by former lawmaker and Sokha-ally Yem Ponhearith. The KNP will contest about one-third of the total 1,652 communes next year.

The party is running on a pro-democracy platform promising to respect human rights and restore freedoms that Ponhearith says have been on the decline.

“If there is no social justice, conflict will remain,” Ponhearith told party comrades during International Human Rights Day celebrations this year, some four years after the dissolution of the CNRP.

However he warned against continued in-fighting on social media between Rainsy and Sokha, saying Cambodians were tired of the ”politicians’ endless argument.”

Last month on his Facebook page Sokha accused Rainsy of continuing to use his name and photo in connection with political activities without his support, stressing that he and his former colleague were “not the same person.”

Meanwhile Rainsy alleged Sokha’s comments were “the result of threats from Hun Sen, who dreads unity among Cambodian democrats and who is holding Kem Sokha hostage.”

Ponhearith said opposition politics need to move forward and they must not allow a repeat of 2017, when the 5,000 opposition councillors never got to take up their positions because the CNRP was dissolved.

For his part, Kheuy Sinoeurn, vice president of the Cambodia National Love Party, said that the CNLP would go to the polls to continue the work of the now defunct CNRP.

“We were former CNRP officials, and we are continuing the spirit of the CNRP,” he said, adding that his party hoped to win some 80 precent of the communes next year — an ambitious goal.

“People want change, so we believe that people will support our party and we can compete with the ruling party,” he added.

Asked whether voters won’t be confused by the many splinter groups running and the Sokha-Rainsy split, Sinoeurn demurred.

“There is no impact on the Cambodia National Love Party because we follow the spirit of CNRP,” he said.

Sinoeurn added that local officials from the ruling party have been persecuting and intimidating opposition members and called on the government to reopen the democratic space and let the opposition campaign freely.

Like Sinoeurn, Ouch Chanrath of the Cambodia Reform Party, said that CRP has also upheld the spirit of the outlawed CNRP to attract voters in the upcoming election.

However, he noted that due to the pandemic and financial constraints the party couldn’t campaign as widely as they would like.

“The source of our finances comes entirely from our party’s members and leaders,” he added.

He also expressed concern the public would hesitate to participate in the election due to a lack of confidence in the National Election Committee, which is seen as biased towards the ruling party.

He is considering using an old CNRP campaign slogan: “Change commune chiefs who serve the party and replace them with commune chiefs who serve the people,” which the CPP said at the time amounted to incitement.

Another opposition splinter party running, the Candlelight Party, which was previously known as the Sam Rainsy Party and later merged with Kem Sokha’s Human Rights Party to form the CNRP, held a congress last month to restart the organization so it could contest next year’s vote. But the party says it will only participate if there is no pressure or intimidation.

“We will receive commune seats because our forces are the same, and we have just reconnected to turn the wire back on,” said the Candlelight Party’s vice president Thach Satha.

The Khmer Will Party is another party formed in the wake of the CNRP’s Supreme Court-ordered dissolution. The party ran in the 2018 national election, but did not win a seat.

It’s president, Kong Monika, said financial limitations are hampering the party’s ability to participate.

“We don’t have a large structure yet, and we (campaign) based on our limited capacity,” Monika said, adding that it is the first time the Khmer Will Party will join a commune election.

Minor Parties Seek to Make Their Mark

Meanwhile, some minor political parties have doubled their candidates but are still unable to contest all communes.

Sam Inn, a secretary-general of Grassroots Democratic Party (GDP), said his party will be able to run in 100 communes in 2022, compared to only 27 in 2017. During that contested election it saw five commune councilors win in three communes.

The GDP was founded in 2015 by former non-governmental organization leaders, as an independent political party, and won no seats in the 2018 parliamentary election.

He said that while the GDP hasn’t grown as much as they would like, they hope to win seats in areas like Phnom Penh, Kampot, Kampong Speu, Siem Reap, Kampong Thom and Ratanakkiri where they have networks.

Mr. Inn said next year the GDP will focus on the economy, labor issues, the agricultural sector and good public services among other issues,

“We will push the Cambodian People’s Party to do good things, to serve citizens, and if they don’t change, other communes will want to follow the model of GDP communes,” he added.

Nhek Bun Chhay, president of Khmer National United Party, is using a similar strategy to contest only 50 percent of the communes due to financial challenges.

In the 2017 election, the KNUP gained 274 commune councilors, including one commune chief seat, after leaving the royalist Funcinpec party in 2016.

“We hope to double the number [of candidates] because now we have enough time and a good environment,” Mr. Bun Chhay said, noting that in the last elections he’d had only eight months to prepare.

He said that their campaign message for the 2022 elections will focus on adhering to the principles of the 1991 Paris Peace Agreement.

An Uphill Battle

Despite the confidence expressed by some of the opposition leaders mentioned above, Korn Savang, an advocacy coordinator at the Committee for Free and Fair Elections in Cambodia (COMFREL), said the reality is they face a tough road ahead.

He said that the CPP has built its base for decades, and even though the CNRP came close in 2017 they still didn’t win as many communal seats as the ruling party.

However, he said an opposition victory wasn’t outside the realm of possibility, noting; “The splinter groups of former senior CNRP officials will attract voters.”

Either way, he stressed, the priority is not that the opposition win, rather that they participate and build public trust.

However, Pa Chanroeun, president of the Cambodian Institute for Democracy, said so many opposition parties will only lead to a splintered ballot, with the CPP set to retain the majority of commune seats.

“In our electoral system, the smaller groups have less chance of getting either commune seats or the National Assembly seats,” he said.

“Light-weight parties that have no ability to contest all communes reflect the lack of a credible opposition to take on the heavy weights [CPP],” Mr. Chanroeun said.

He also noted that in Cambodian politics, people are more likely to support individual politicians than political party platforms.

“The splitting of the former CNRP leaders [alliance] has a negative impact on new parties” in terms of their getting public support, he said.

CPP Looks to the Past — and the Future

CPP spokesman Sok Eysan, told CamboJA that the ruling party welcomes opposition parties who intend to participate in the commune election, which he said shows Cambodia is a multi-party democracy.

“We consider every political party participating in the election our competitor, and we do not take them lightly,” he said.

Next year, two months before the polls, the CPP will hold its congress and approve candidates to contest the election in all communes nationwide, Eysan said.

Voters will remember the CPP liberated the country four decades ago, he added.

In October, Interior Minister Sar Kheng said that rather than rely on slogans referencing the end of the communist regime 41 years ago, candidates from the ruling party should address grassroots issues affecting the public.

He pointed to land disputes as an important issue of focus.

“If we just propagandize our achievement on January 7, in fact, it’s already known,” Mr. Kheng said. “So, what do [people] need now? [we] must look at issues to resolve with accountability and justice,”