After the Trump administration this year axed most U.S. foreign aid and public broadcasters serving parts of the world with scant press freedom, the fallout laid bare the shaky crutch propping up independent media in underserved regions.

In 2024, before the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) was dismantled and absorbed by the State Department under the second Trump administration’s “waste, fraud and abuse” cuts, Congress approved nearly $272 million for “Independent Media and Free Flow of Information.”

Most of these funds went directly to journalism and media development in regions across the world lacking independent news outlets.

After the rollback scrapped the initiative and dozens of similar country-specific programs, many independent newsrooms from Afghanistan to Myanmar and Cambodia lost all or most of their operating budgets, casting doubt on the sector’s survival.

In more than 50 countries, newsrooms have shut down, reporters have lost jobs and disinformation threats have grown, according to an assessment of the cuts by a consortium of media development groups.

The successive blow came weeks after USAID was forced to cut 80% of its programs in March, when the Trump administration issued an executive order dismantling public broadcasters Voice of America (VOA) and Radio Free Asia (RFA), two crucial sources of balanced news for millions in Southeast Asia.

In Cambodia, which has struggled for decades to keep media outside state influence alive, coverage of democratic backsliding, indigenous rights, the online scam industry, environmental crime, critical journalism itself and other sensitive topics has thinned. The few remaining independent journalists and newsrooms are seeking alternative donors or commercializing to replace U.S. aid, which has been hard to match.

Veteran reporters who once covered these beats now take on alternative livelihoods to sustain themselves. Vulnerable communities say they feel unheard.

As Independent Media Fades, ‘It’s Like Closing Our Eyes and Ears’

Lan La, a Kuy indigenous resident of Mondulkiri province, was a regular listener to RFA’s Khmer-language radio broadcasts before they went dark.

“Independent media is very important and necessary for spreading information to local communities,” he said. “When they are closed, we are helpless and do not know how to get our problems heard.”

RFA was forced to suspend operations in Cambodia in 2017 amid rising crackdowns on free press. Many of its reporters went into exile – some even jailed – but it continued to broadcast and publish reports on Cambodia until it was effectively shuttered this year.

Fewer than a handful of independent newsrooms still consistently report on issues affecting marginalized groups, including CamboJA News, which relied on U.S. funding.

The $7 million USAID-funded Cambodian Media Development Activity, a flagship initiative relied on by a handful of nonprofit newsrooms and media development groups to cover underreported issues, was one of the projects axed earlier this year.

Longtime Prime Minister Hun Sen, who handed power to his son in 2023, lauded Trump after he cut funding to RFA, calling it a “major contribution to eliminating fake news, disinformation, lies, distortions, incitement and chaos around the world.”

But La said such outlets have been vital in raising awareness of problems in rural and indigenous communities, particularly land rights and forest crimes – two entrenched issues facing the country.

Several other indigenous and rural community members CamboJA News spoke with said the same. The absence of independent media and the reliance on RFA and VOA radio, a main source of news for many Cambodians, has hurt reliable, critical journalism and left a gap in coverage of issues that matter most to them.

“When independent media is lost, we end up with incomplete information and lose trusted sources,” La said, hoping the U.S. president would restore funding for media development and broadcasters in Asia.

For activists like Sea Davy, a land rights defender from Boeung Tamok, the decline of independent media has direct consequences for social justice.

“Without these outlets, our advocacy is lost. It’s like closing our eyes and ears,” Davy said. She warned that as press space shrinks, social injustices are likely to multiply unchecked.

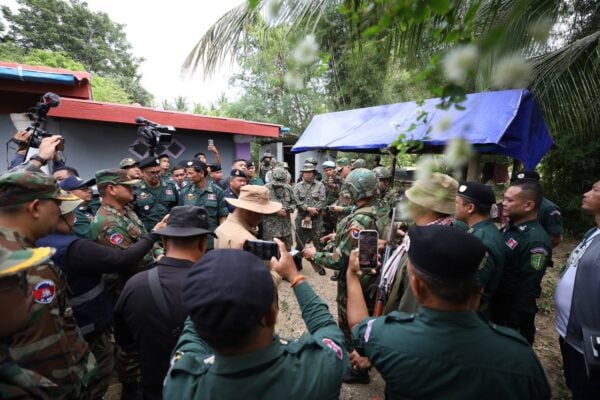

While the government claims press freedom is alive and well, citing figures that clash with Cambodia’s low ranking on the global press freedom index, the limited international and independent media in the country again became a public talking point during recent border clashes with Thailand.

Many Cambodians criticized what they saw as biased or limited coverage of the conflict – a shortfall observers attribute to the country’s depleted press corps.

From the Newsroom to Working Sales

Meas Da once reported on labor and land disputes for VOA Khmer. Now she works in a Phnom Penh cosmetics store.

“I never thought the place we worked with such passion would close so suddenly,” she said while on a weekend break. “It felt like losing a part of myself. Journalism wasn’t just a job – it was a way to give a voice to those who are never heard.”

Despite her reporting background and journalism degree, Da turned to selling cosmetics after VOA furloughed the Khmer team, saying most newsrooms in Phnom Penh and beyond shy away from the critical topics she cares about, while a funding crunch at the remaining independent outlets has left scant job opportunities.

Da’s former VOA colleague, Lors Liblib, faced the same dilemma in Cambodia’s shrinking professional journalism market. After three years of reporting for the shuttered outlet, he became a real estate agent in the capital.

He still hopes to return to VOA one day and that nonprofit newsrooms will secure the funding to keep covering human rights and politics without influence.

VOA’s fate now rests with several U.S. federal judges weighing lawsuits that challenge the authority of Trump appointee Kari Lake, head of the U.S. Agency for Global Media – the federal parent of VOA, RFA and other international broadcasters – to close the congressionally funded outlet.

For freelance journalists in Cambodia and the region, long-form reporting on topics such as environmental issues has depended largely on U.S. support and global media development organizations.

Meng Kroy Punlok, a young Phnom Penh-based journalist, said he once published 10 stories a month on land rights, environmental degradation and political issues with the help of grants and freelance budgets from nonprofit newsrooms.

“The loss has emptied my pockets and weighed heavily on my mind,” he said. “I thought about giving up journalism entirely, but I can’t abandon the work.”

Organizations such as the Earth Journalism Network, whose anchor funder was once USAID, provide story grants, training, resources, and mentorship for journalists such as Punlok in low- and middle-income countries focusing on environmental reporting.

The group has shifted more toward alternative donors after the rollback of U.S. aid, including Sweden’s international development agency, to keep funding reporting in the Asia-Pacific region. While it secured grants in March for environmental coverage in underserved newsrooms in the region, none went to Cambodian outlets.

Lost Outlets, Lean Operations: Free Press on the Edge

Over the past 30 years, the U.S. has given Cambodia $3 billion in aid for health care, education, food security, economic growth, democracy, human rights, environmental programs and clearing unexploded ordnance.

U.S. funding for public-interest newsrooms in Cambodia first became prominent in 2003, when local outlet Voice of Democracy launched with USAID support.

The outlet, which helped break the story on the burgeoning scam industry in Cambodia, was shut in February 2023 after then-Prime Minister Hun Sen revoked its license over a report he said misrepresented his son Hun Manet’s role in approving foreign aid.

Months later, Hun Sen handed power to Hun Manet.

The closure was seen as removing one of the last pillars of independent media, after The Cambodia Daily closed in 2017 over a disputed $6.3 million tax bill and the Phnom Penh Post was sold in 2018 to a businessman with government ties, prompting mass resignations.

For nonprofit media still covering sensitive topics such as threats to the rule of law while often fearing reprisal in the process, past reliance on USAID has destabilized operations, forcing cuts and uncertainty as outlets scramble for alternative donors or even try to commercialize. It also has prompted them to reevaluate their sustainability models.

Cambodian Journalists Alliance Association (CamboJA) executive director Nop Vy said the NGO, which provides media training, advocacy research into press freedoms, and hosts the CamboJA News publication arm, relied on USAID grants for more than half its operational expenses, similar to many other civil society groups in the country.

“CamboJA has tried to engage many alternative partners, but only a few have provided support, as they have limited budgets and capacity themselves,” he said, noting that some European nations have also rolled back foreign aid this year.

“To avoid reducing or cutting staff, we’ve trimmed costs elsewhere – moving to a cheaper office and scrutinizing every expense, down to coffee and meeting refreshments.”

Vy said the return of some U.S. donor funds after federal court challenges, along with efforts to diversify the group’s donor pool, has eased pressure. Still, long-term planning remains a daily concern.

Financial sustainability is one of the main concerns for journalists in Cambodia, both at media organizations and individually. A survey of 100 journalists by the Cambodian Center for Independent Media found that more than 70% cited it as a concern.

Ninety-one percent reported feeling unsafe due to their work.

For Kiripost, a local independent newsroom that received some USAID funding and reports mainly on business and tech news, quick – but challenging – pivots to commercialization may be the path forward.

“For news organizations still able to adapt, immediate action is crucial – prioritize monetization and secure the future of your newsrooms,” CEO Prak Chan Thul said.

When asked about the fallout of U.S. assistance for the media in Cambodia, Ministry of Information spokesperson Tep Asnarith said the government welcomes international cooperation to expand citizens’ access to information, but only on the condition that it “respects Cambodia’s sovereignty and independence.”

“The Ministry of Information calls on all donor countries to adhere to truth, neutrality and high responsibility in their projects, without linking assistance – whether technical support or funding – to agendas that may affect Cambodia’s sovereignty and independence, or exploiting the media to serve their own politics,” he said.

The government has long accused journalists at U.S.-funded outlets and activists with Western-backed groups of serving foreign interests or siding with opposition parties, many since dissolved or banned. In 2017, two former RFA reporters were jailed for more than a year on espionage charges after continuing to work following the broadcaster’s Phnom Penh bureau closure.

As Cambodia’s independent newsrooms cling to life, the challenges of lost U.S. funding and political pressure are echoed across the globe.

Media development groups report similar blows to exiled outlets from Myanmar and other fragile democracies. Continued shocks could hollow out free press globally, leaving communities without reliable information and amplifying state narratives.

For journalists still reporting, survival depends on innovation, international support and the hope that audiences – and donors – keep backing reporting that holds power to account.