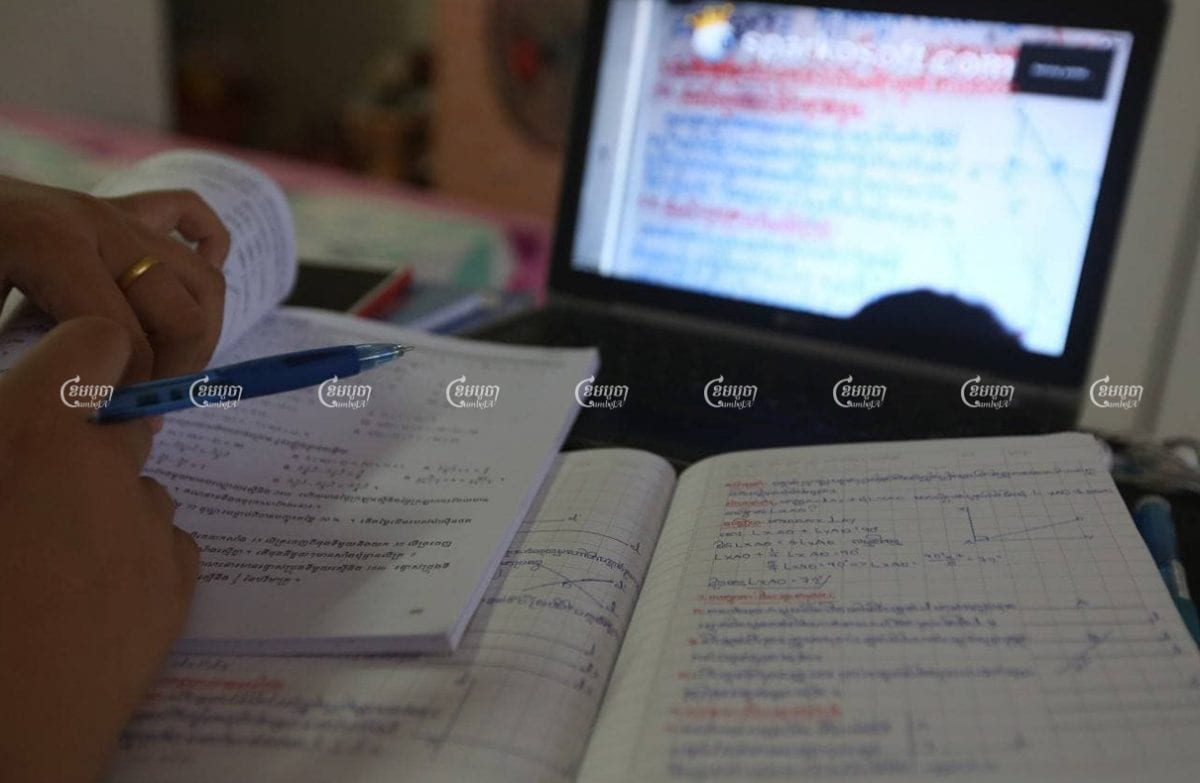

As schools are suspended in the wake of the third Covid-19 outbreak, children and parents across Cambodia are bracing for a return to online learning.

But for many, the move away from a formal classroom puts a pause on their schooling – and comes with the risk that they will never return.

“My three children learn nothing,” Seng Try, a 50-year-old scavenger living in Phnom Penh’s Prey Sar commune told CamboJA, explaining that they do not have a smartphone or computer to access the Internet.

“They help me with my scavenging some days,” she said of her children, who are between grades five and nine. “If schools stayed closed for long, I am concerned that they will know nothing.”

Cambodia’s third – and most serious – wave of Covid-19 has already seen schools shut down in Phnom Penh, Kandal, Preah Sihanouk and parts of Prey Veng and Koh Kong provinces, as the caseload from the “February 20” outbreak continues to climb.

Around the world, educators have been put to the test by school shutdowns over the past year, with the shortcomings of online learning exposed as some of the most vulnerable people are unable to access lessons.

With this in mind, Cambodia will look to minimize shutdowns that threaten an already weak education system, said Education Minister Hang Chuon Naron.

“The ministry is doing hourly and daily evaluations of the situation, especially in rural areas where there is not the high risk of COVID-19,” he told CamboJA.

“We cannot close (schools) across the country as it will affect the study of students in areas that are not affected by COVID-19.”

The World Bank reported last December that the COVID-19 pandemic and school disruptions could push 72 million additional primary school children into “learning poverty,” described as children who are unable to read and understand a simple text by age 10.

Children from poor and rural backgrounds face the most significant challenges, said Katheryn Bennett, chief of education for UNICEF in Cambodia.

“These challenges are exacerbating existing challenges of high student dropout rates, poor learning outcomes; rural/urban disparity; education accessibility; and limited school infrastructure,” she said.

Using Education Ministry data, UNESCO estimates that 500,000 students from nearly 800 schools in Cambodia had been affected by the school closures in 2020.

Aside from closures to stop the spread of COVID-19, about 50 schools in the northern provinces bordering Thailand have been converted into quarantine centers as tens of thousands of Cambodian migrant workers return from Thailand.

The repurposing of schools as quarantine centers has brought its own range of challenges, said In Khin, a deputy principal at a secondary school in Oddar Meanchey province’s Samrong district.

Students have been transferred to a nearby primary school, where they split time in the already full classrooms, he said.

“Students do not have full access to schooling,” he said. “We cut some schedules because we have not enough classes.”

With the pandemic creating an uncertain future – and having already stunted the learning of many – the gap between the poor and wealthy is likely to be exacerbated, experts say, with many children forced to take on work while not at school, creating a risk that they may never go back.

Cambodia could be among countries hit hardest by these inequalities, with a big gap in quality between the online learning provided by public schools and that provided by private schools, said Mengly J. Quach, chairman of Mengly J. Quach Education, parent of the Aii Language Centers and American Intercon Schools in Cambodia.

“For private schools, students have more opportunities, but most of students at public school in rural do not have access to online learning,” he said.

Previous lockdowns have exposed other weaknesses of online learning, he said.

“Children cannot focus on learning online for more than 20 to 30 minutes, so it is difficult for them while parents in developing countries do not have much understanding of technology.”

For those schools that do remain open, the fear of COVID-19 remains high nonetheless, said Leng Pengsor, a physics teacher at Kampong Thom High School, where administrators are considering reducing class hours and gatherings as the third wave spreads across the country.

But remaining open and maintaining high caution was a priority, he said, after online learning proved challenging during previous shutdowns.

“This kind of learning makes (students) careless because we could not follow up and check them up,” he said. “When doing monthly or semester exams, they copy each other, but we also cannot blame them, because at least they can still study.”

Cambodia’s tally of COVID-19 cases has passed 1,300, with more than 800 linked to the third outbreak, known as the “February 20” outbreak, which has now spread to multiple provinces.

While schools outside of the most heavily affected areas remain open, students who are no longer able to attend might swap online learning for a job, as families adjust to life in the pandemic, said Hok Sithak, director of Sipar, an education-focused NGO.

“If more schools continue to close for a long time, students from poor families may drop out of school, especially older students in rural areas who are eligible for the workforce,” he said.

“Because they cannot access full learning … they may drop school and go to work to help the family and they will never go back to school after they join the workforce.”